CDC director has been ousted just weeks after Senate confirmation

Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, told the outlet that Monarez “values science, is a solid researcher, and has a history of being a good manager. We’re looking forward to working with her.”

A low point for the agency

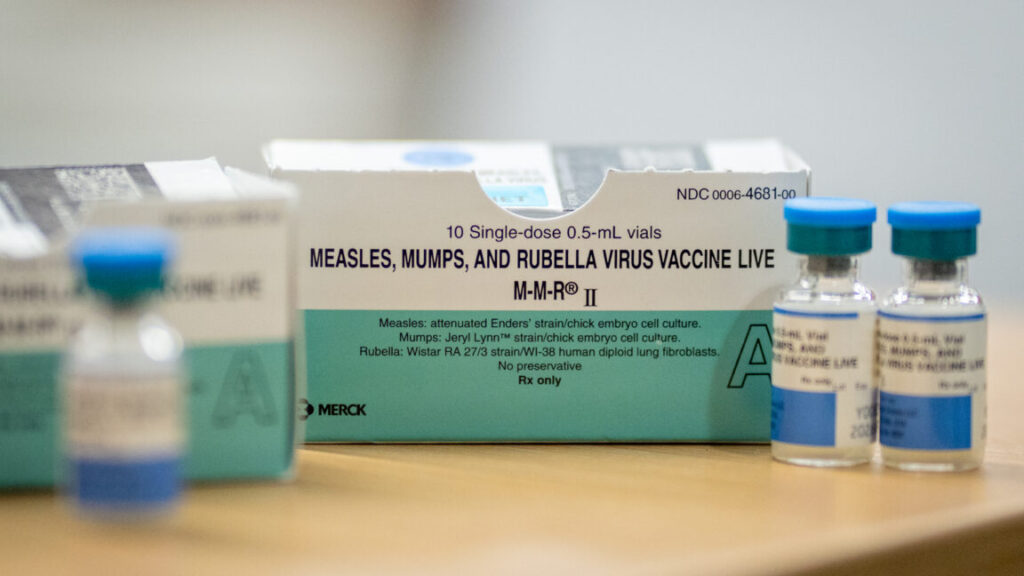

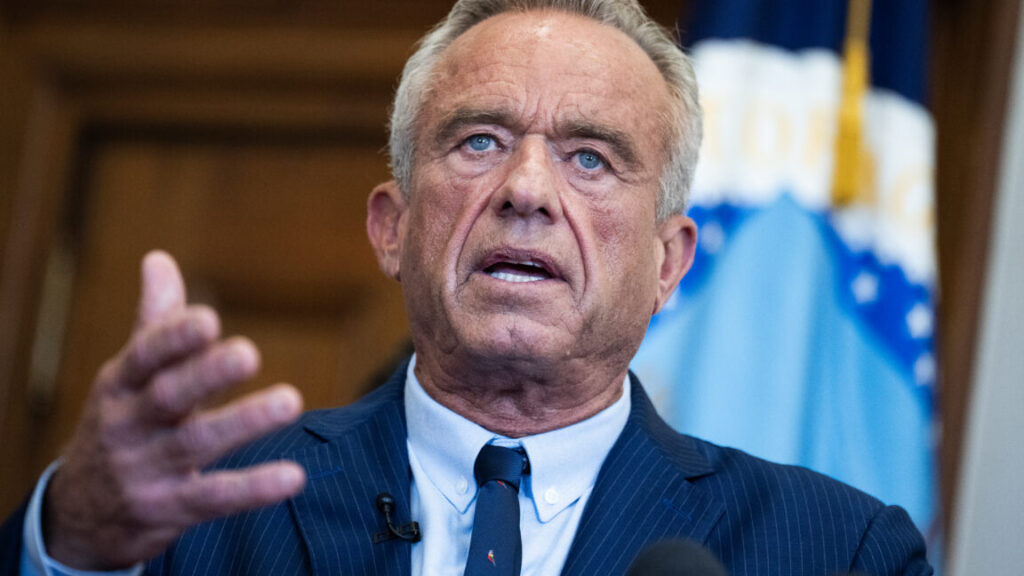

The reported ouster comes at what feels like a nadir for the CDC. The agency has lost hundreds of staff from layoffs and buyouts. Vital health programs have been shuttered or hampered. Dangerous rhetoric and health misinformation from Kennedy and other health officials in the Trump administration have made once-respected CDC experts feel vilified by the public and like targets of hate. Kennedy himself has falsely called the COVID-19 shots the “deadliest vaccine ever made” and the CDC a “cesspool of corruption,” for example.

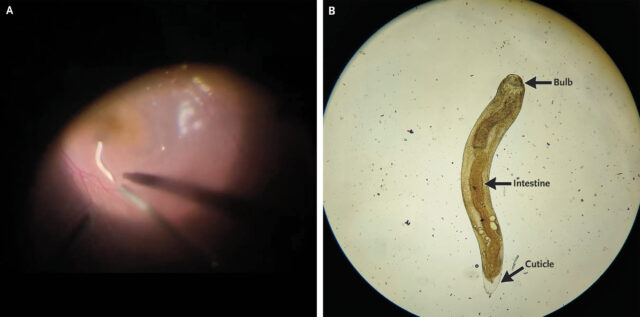

On August 8, a gunman warped by vaccine disinformation opened fire on the CDC campus. Of nearly 500 shots fired, about 200 struck six CDC buildings as terrified staff dove for safety. One local police officer was killed in the incident. The gunman had specifically targeted the CDC for the shooting and blamed COVID-19 vaccines for his health problems.

Additional exits reported

After news broke of Monarez’s removal, Stat News reported that a wave of CDC leadership has resigned. The high-ranking resignations include: Daniel Jernigan, director of the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; Deb Houry, Chief Medical Officer; and Demetre Daskalakis, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

“I am not able to serve in this role any longer because of the ongoing weaponization of public health,” Daskalakis said in a message to staff seen by Stat.

“I am committed to protecting the public’s health, but the ongoing changes prevent me from continuing in my job as a leader of the agency,” Houry wrote in a message to staff. Houry added that science should “never be censored or subject to political interpretations.”

Earlier today, Politico reported that Jennifer Layden, director of the agency’s Office of Public Health Data, Surveillance, and Technology, has also resigned.

8/27/2025 8: 15 pm ET: This post has been updated to include the social media post from HHS, reporting from the Washington Post on the circumstances around Monarez’s exit, additional resignations reported by Stat and Politico, and the statement from Monarez’s lawyers.

CDC director has been ousted just weeks after Senate confirmation Read More »