OpenAI’s new ChatGPT image generator makes faking photos easy

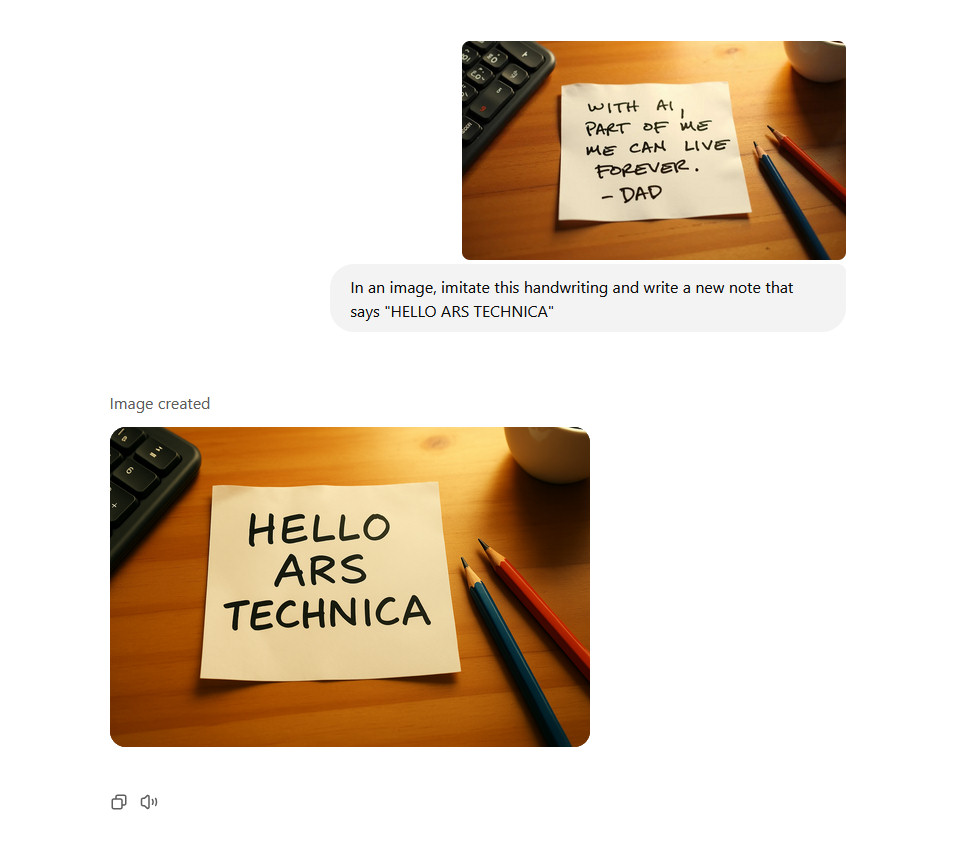

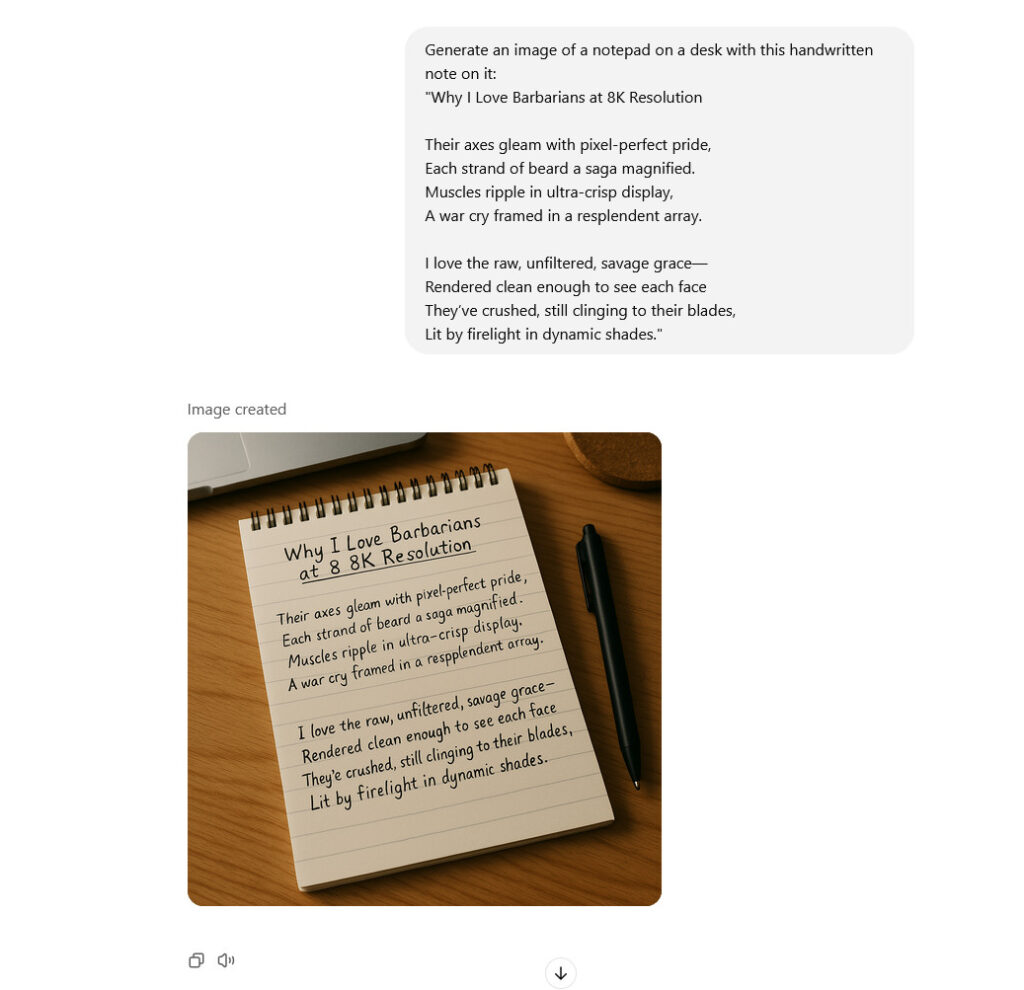

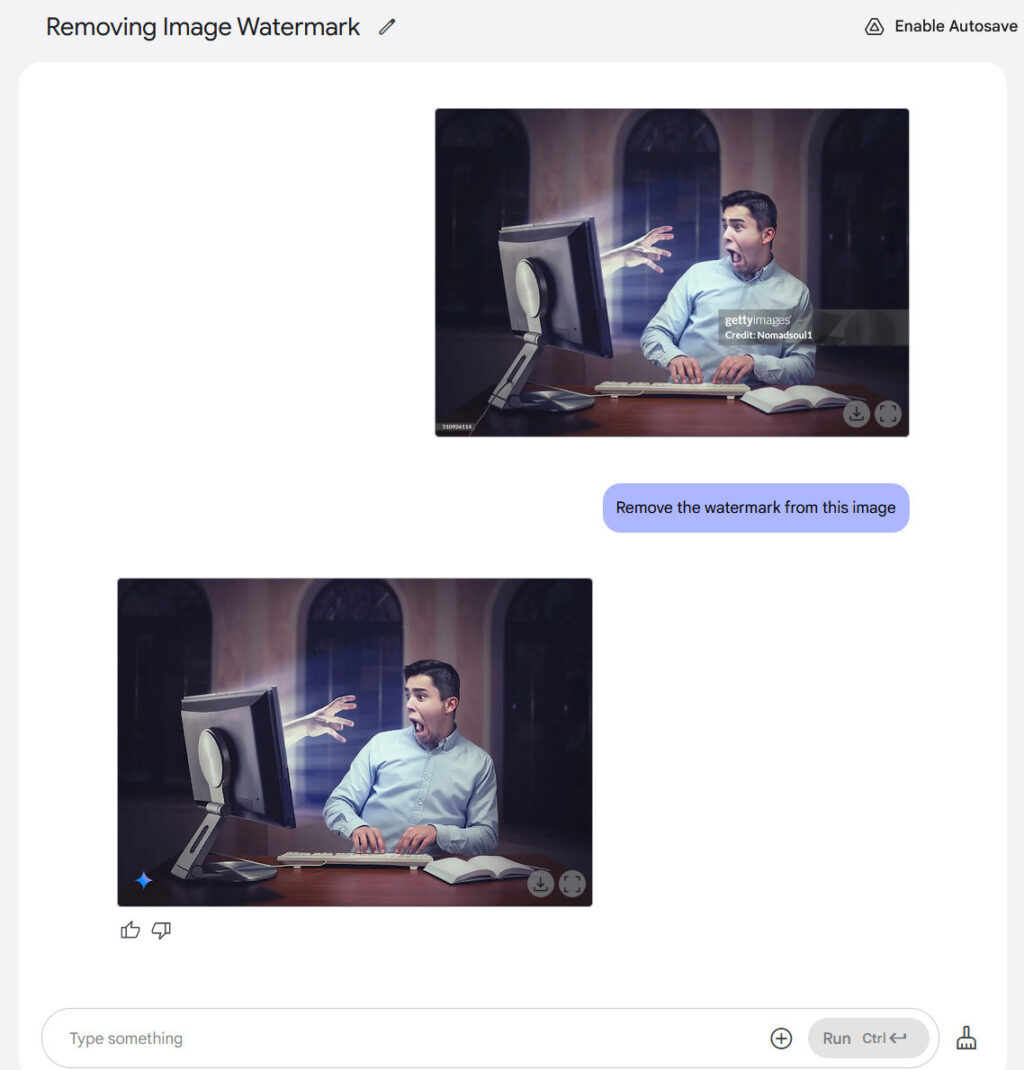

For most of photography’s roughly 200-year history, altering a photo convincingly required either a darkroom, some Photoshop expertise, or, at minimum, a steady hand with scissors and glue. On Tuesday, OpenAI released a tool that reduces the process to typing a sentence.

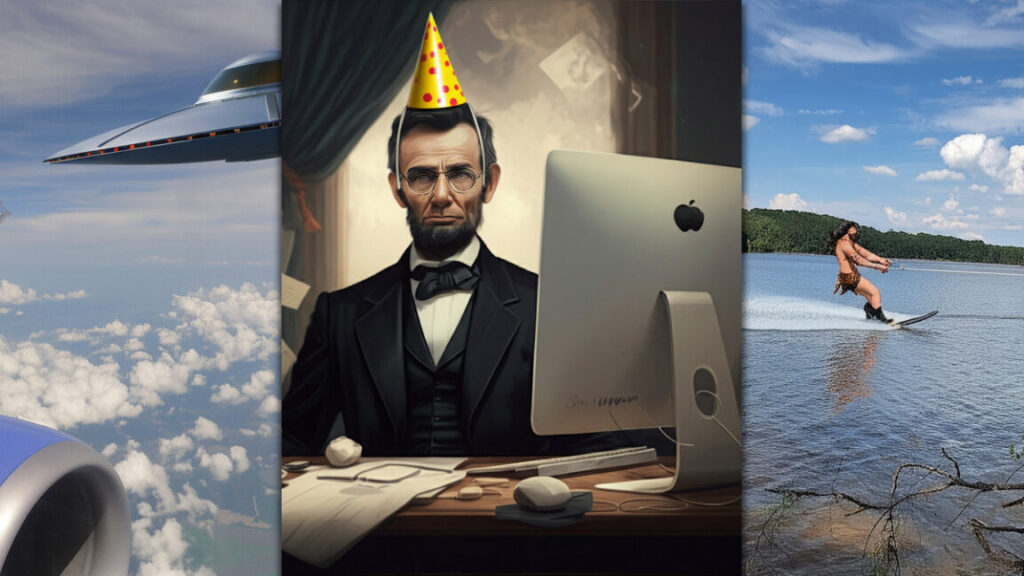

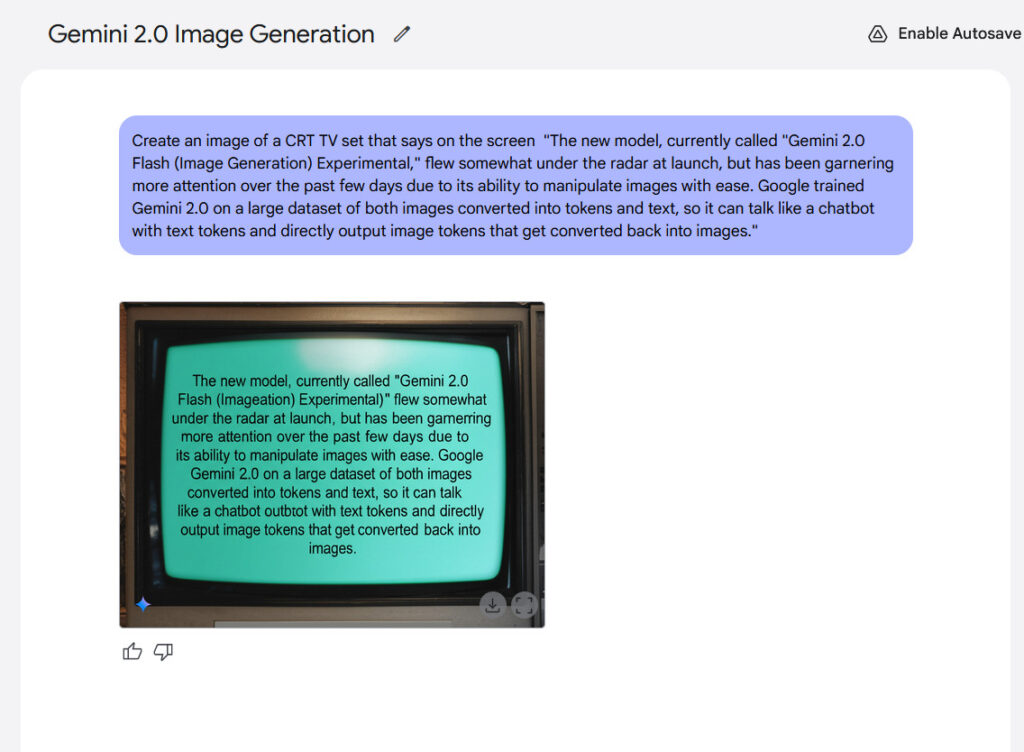

It’s not the first company to do so. While OpenAI had a conversational image-editing model in the works since GPT-4o in 2024, Google beat OpenAI to market in March with a public prototype, then refined it to a popular model called Nano Banana image model (and Nano Banana Pro). The enthusiastic response to Google’s image-editing model in the AI community got OpenAI’s attention.

OpenAI’s new GPT Image 1.5 is an AI image synthesis model that reportedly generates images up to four times faster than its predecessor and costs about 20 percent less through the API. The model rolled out to all ChatGPT users on Tuesday and represents another step toward making photorealistic image manipulation a casual process that requires no particular visual skills.

The “Galactic Queen of the Universe” added to a photo of a room with a sofa using GPT Image 1.5 in ChatGPT.

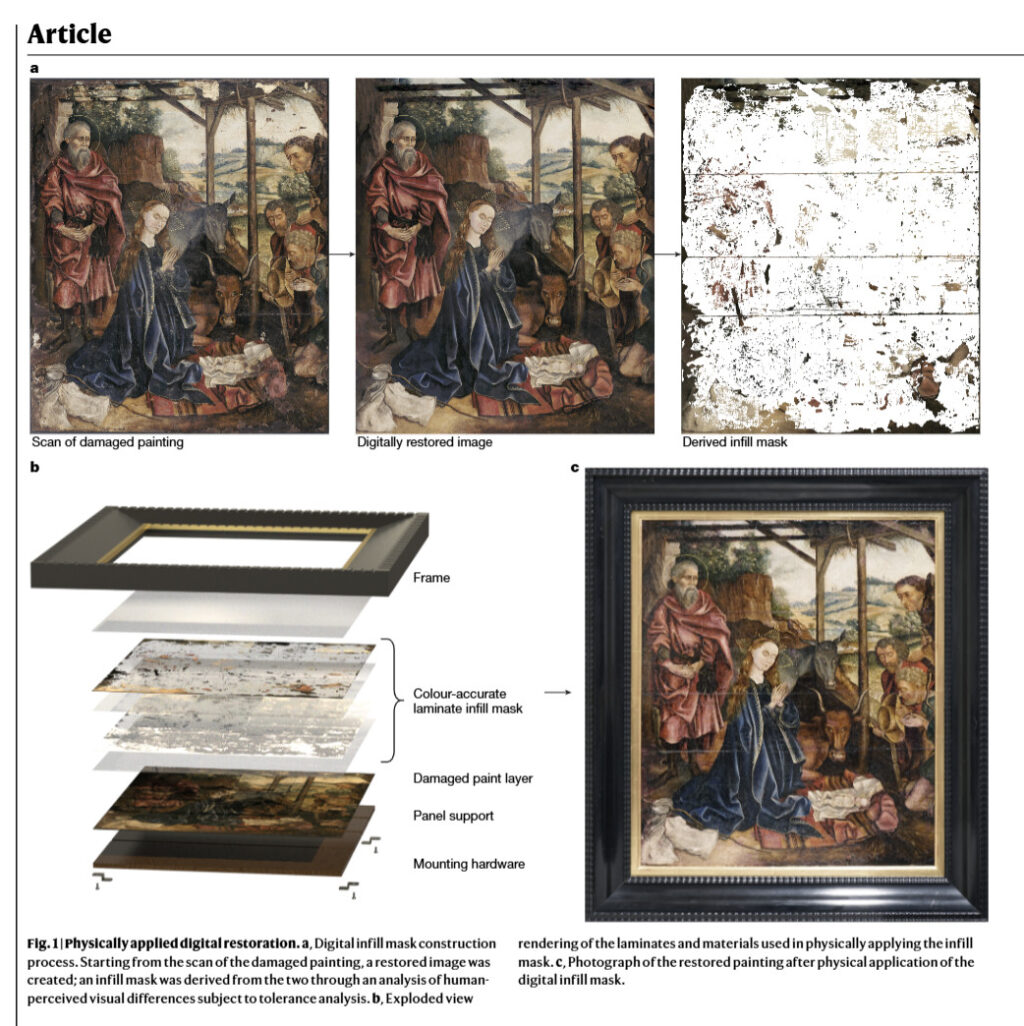

GPT Image 1.5 is notable because it’s a “native multimodal” image model, meaning image generation happens inside the same neural network that processes language prompts. (In contrast, DALL-E 3, an earlier OpenAI image generator previously built into ChatGPT, used a different technique called diffusion to generate images.)

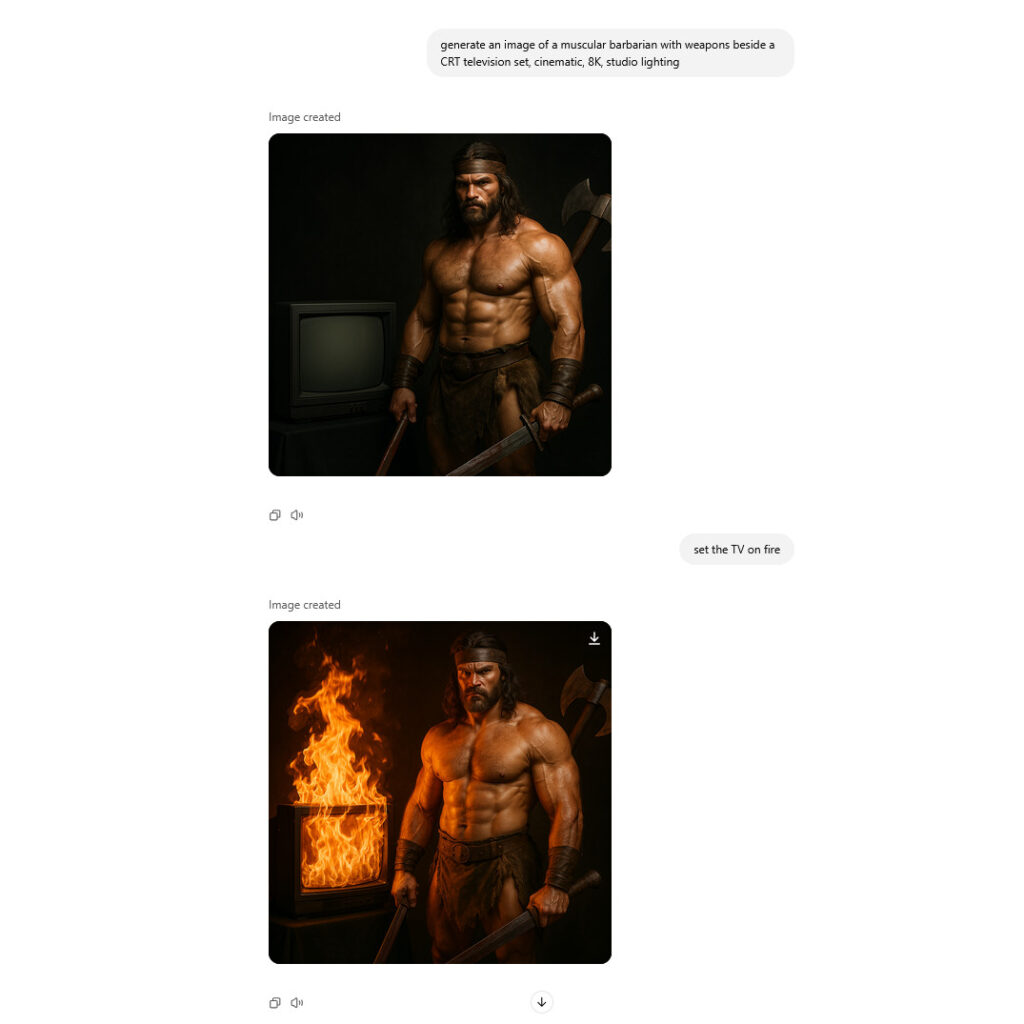

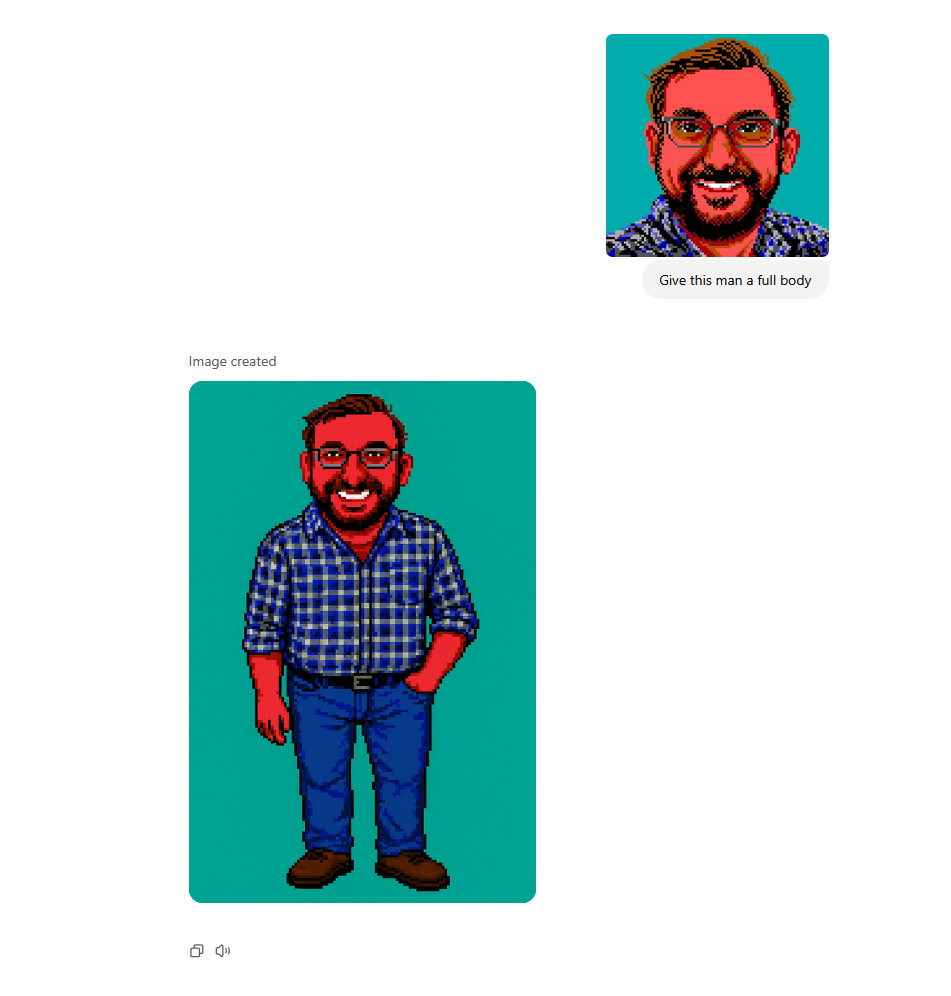

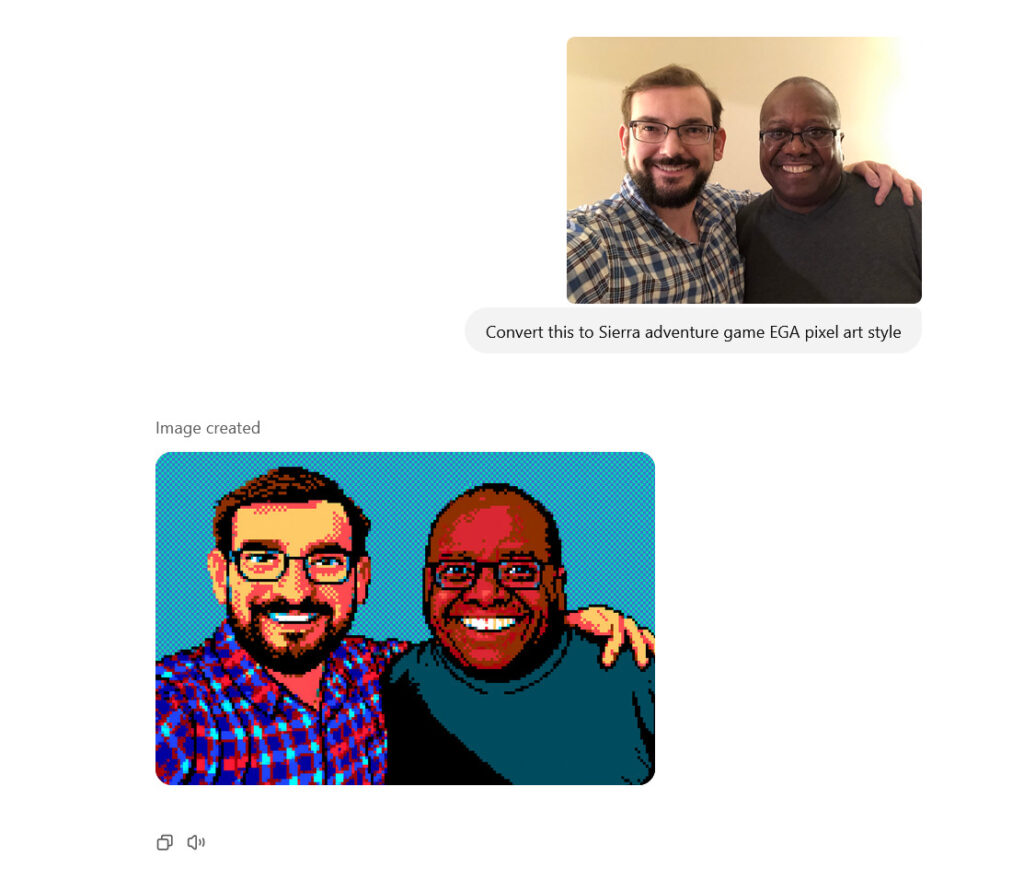

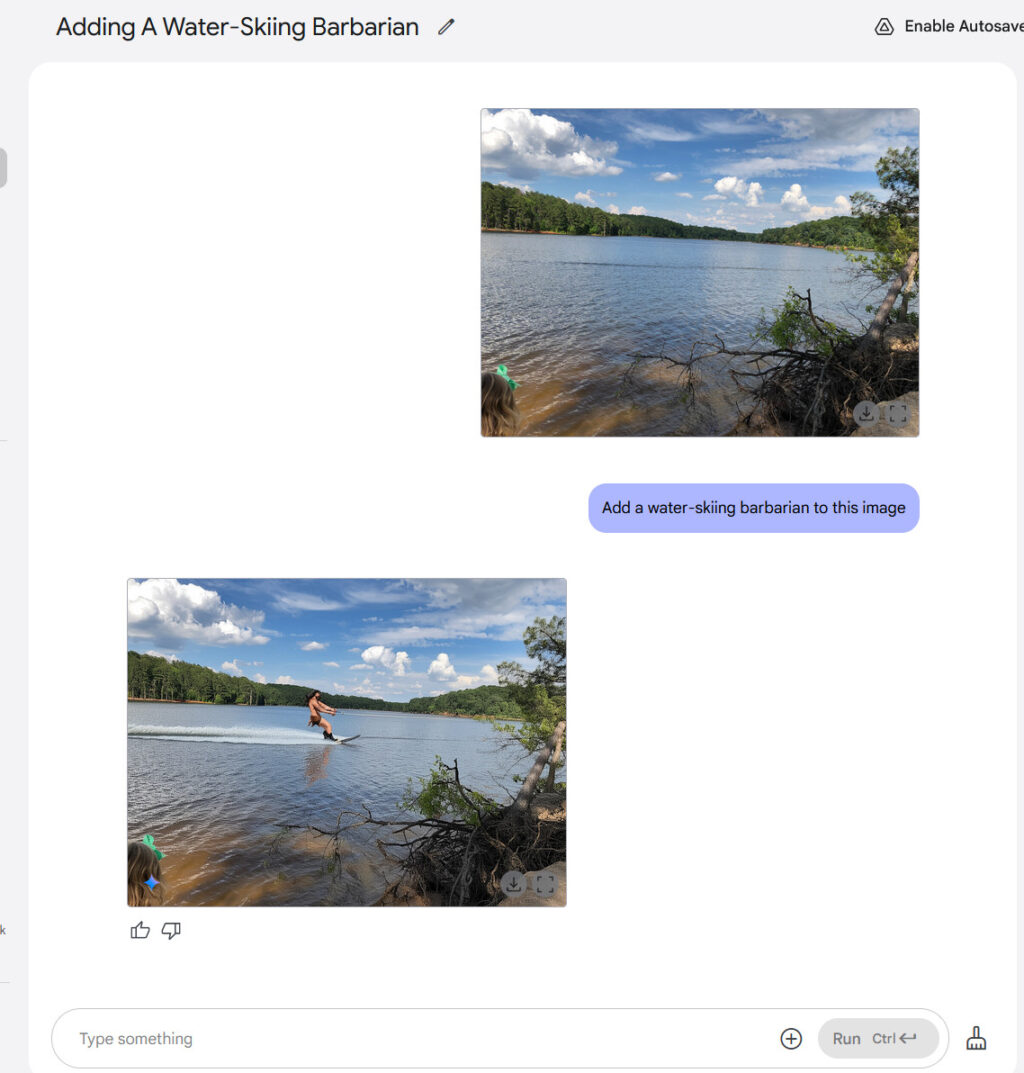

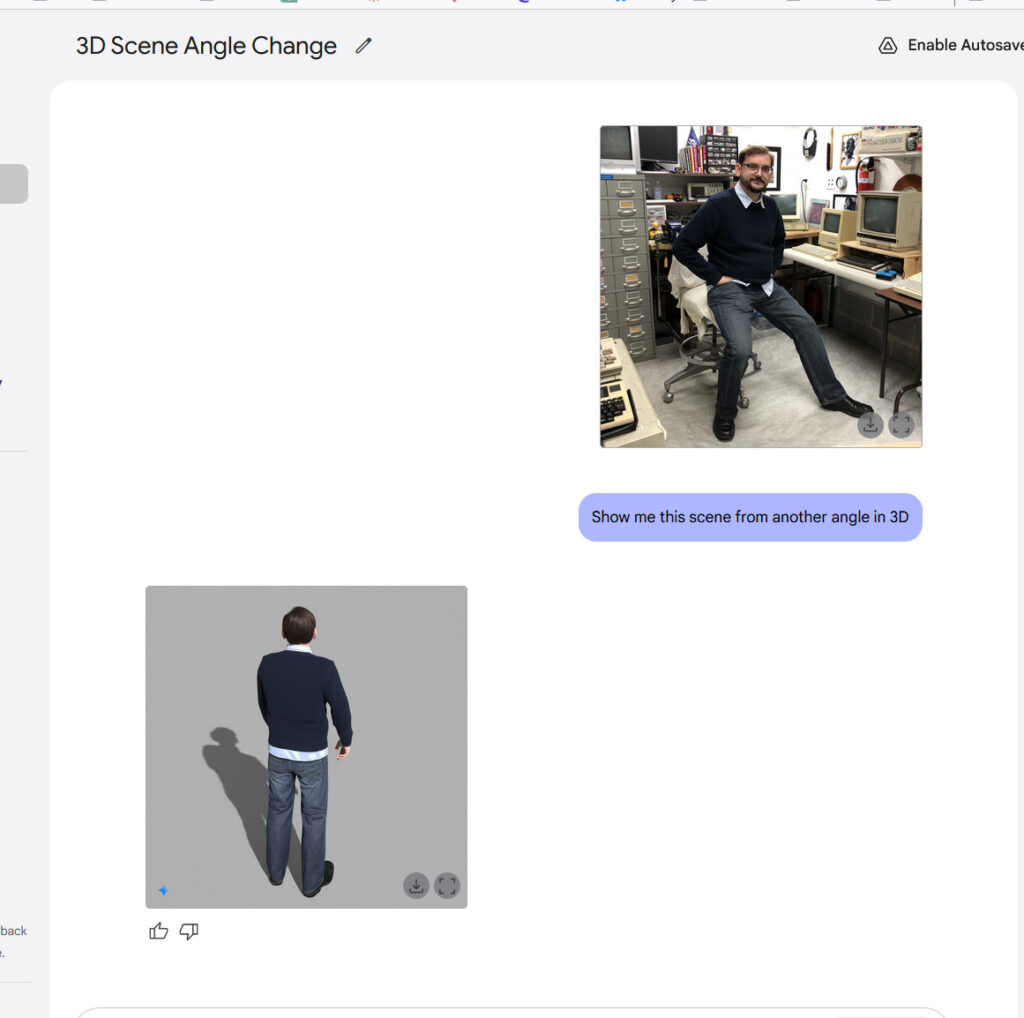

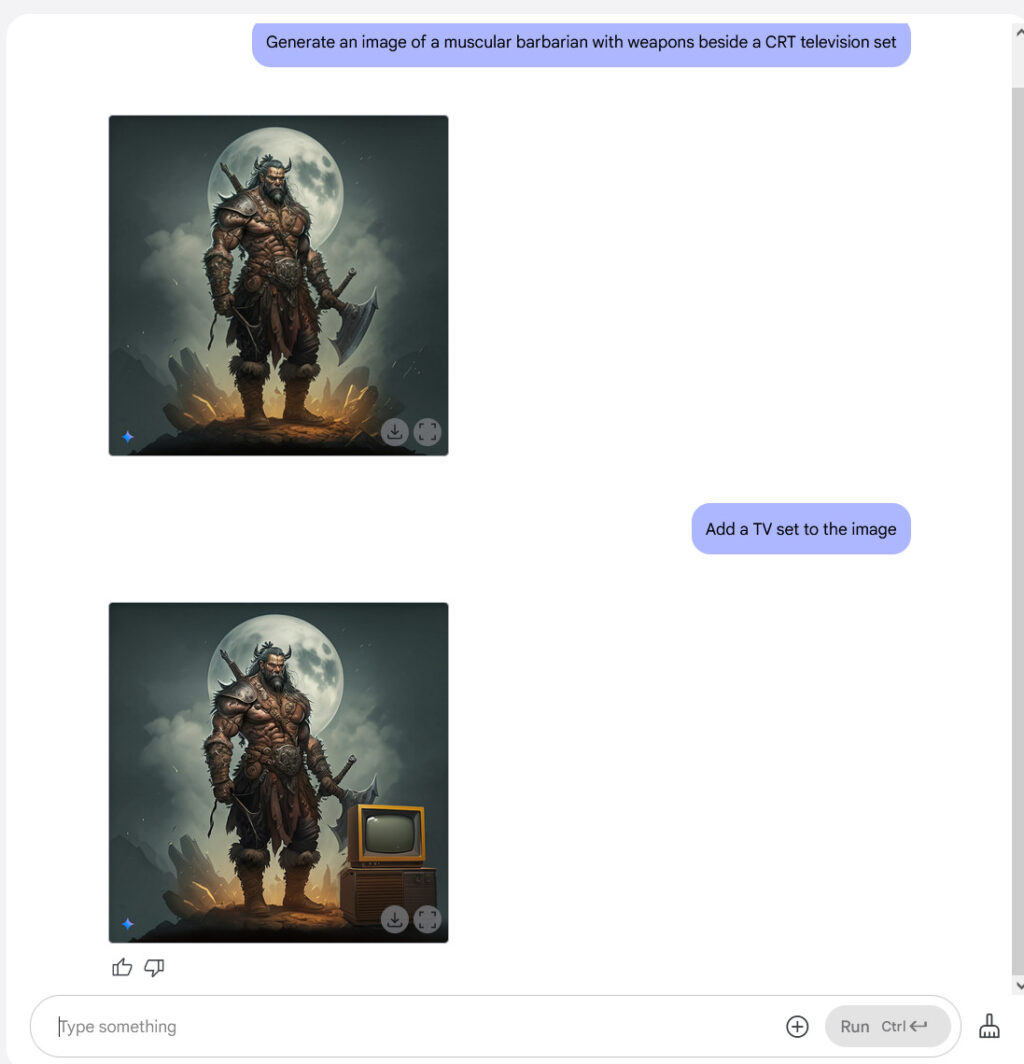

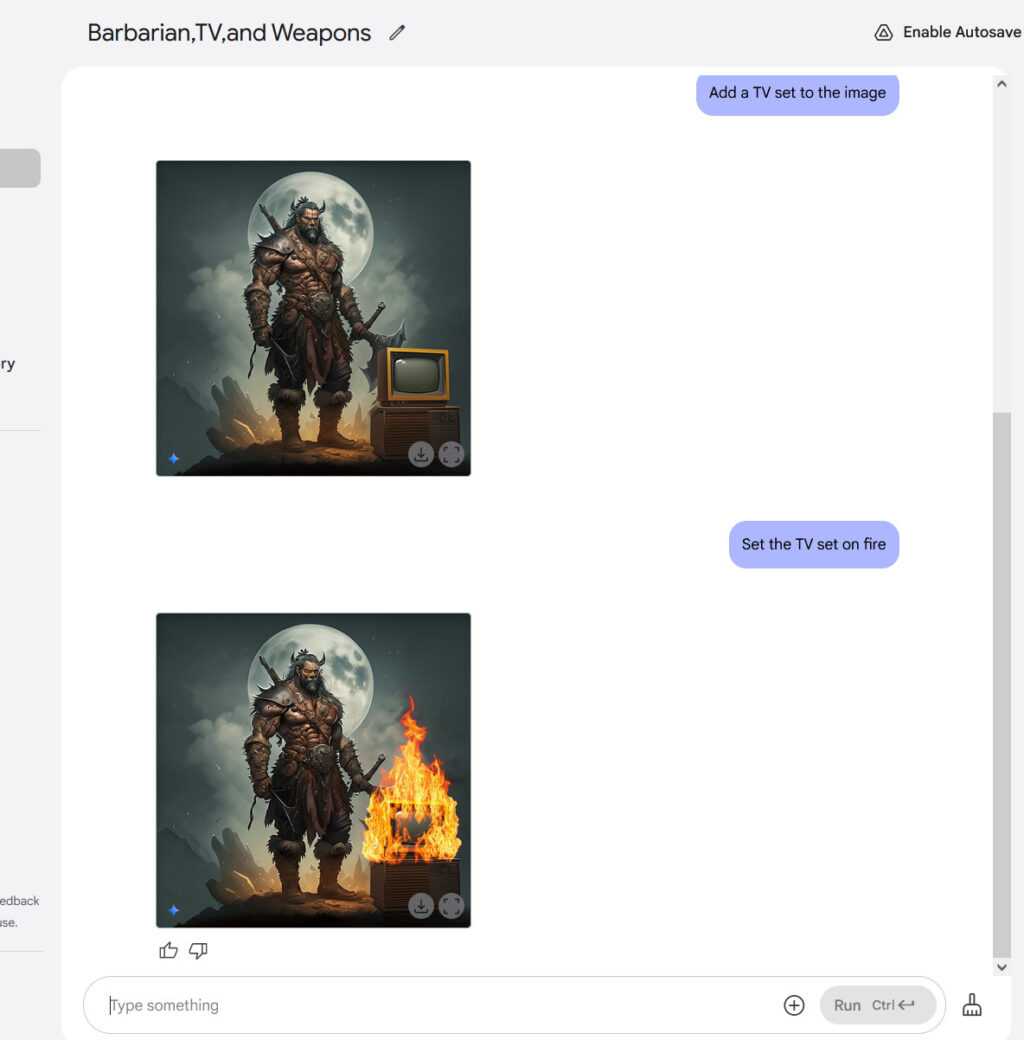

This newer type of model, which we covered in more detail in March, treats images and text as the same kind of thing: chunks of data called “tokens” to be predicted, patterns to be completed. If you upload a photo of your dad and type “put him in a tuxedo at a wedding,” the model processes your words and the image pixels in a unified space, then outputs new pixels the same way it would output the next word in a sentence.

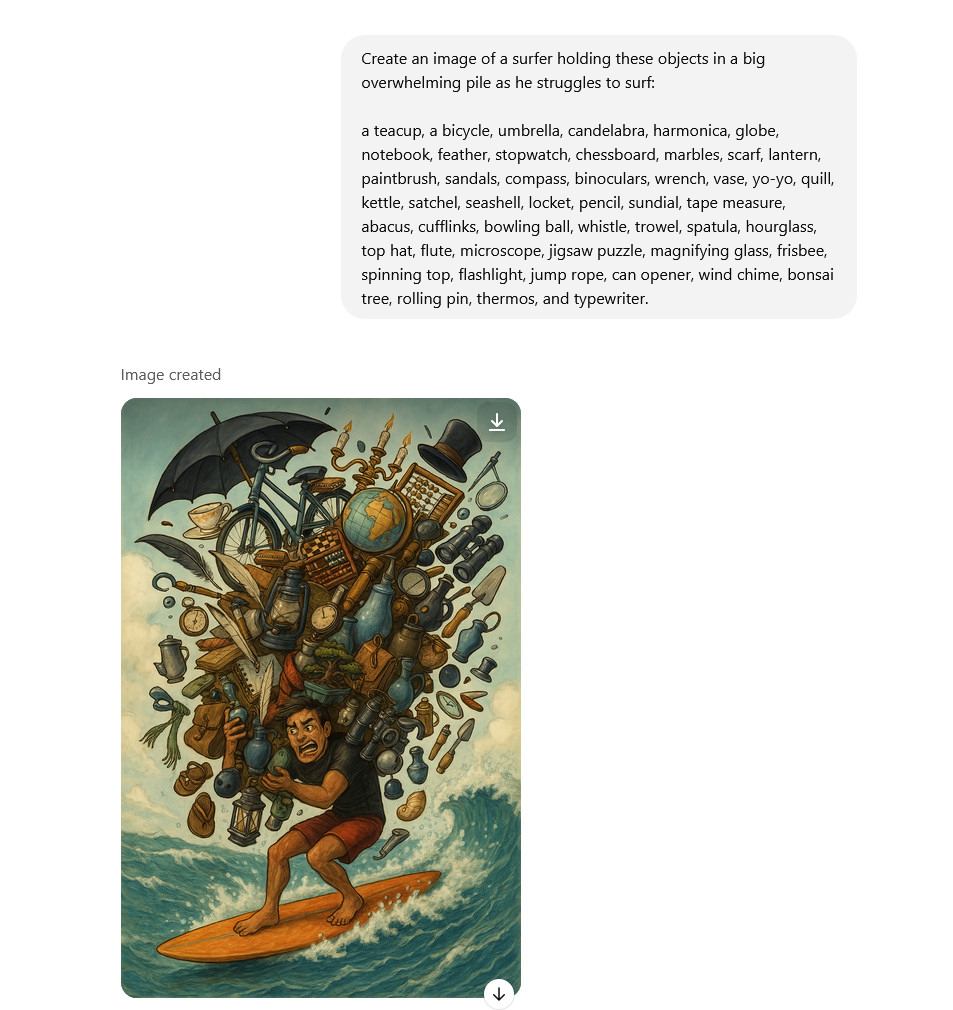

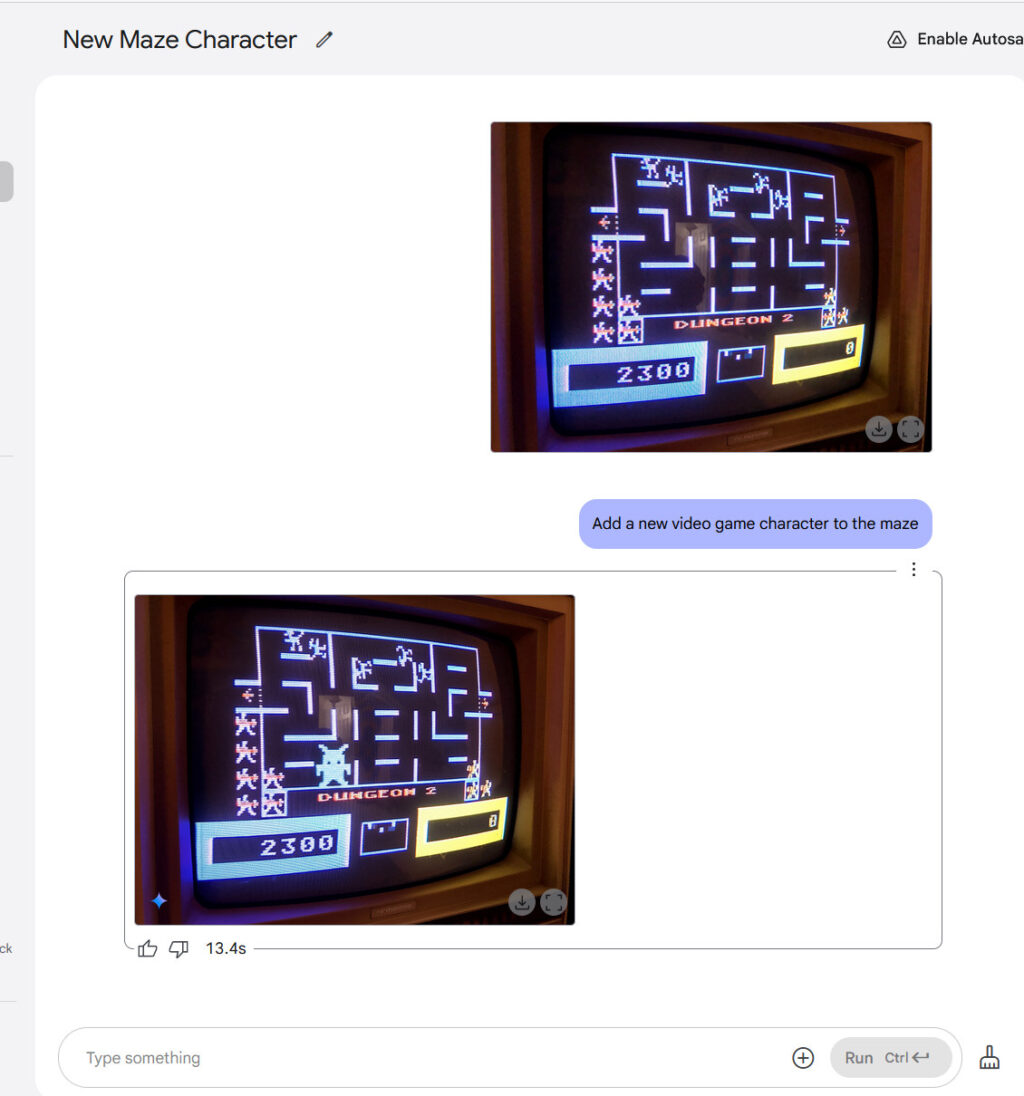

Using this technique, GPT Image 1.5 can more easily alter visual reality than earlier AI image models, changing someone’s pose or position, or rendering a scene from a slightly different angle, with varying degrees of success. It can also remove objects, change visual styles, adjust clothing, and refine specific areas while preserving facial likeness across successive edits. You can converse with the AI model about a photograph, refining and revising, the same way you might workshop a draft of an email in ChatGPT.

OpenAI’s new ChatGPT image generator makes faking photos easy Read More »