Rocket Report: Russia pledges quick fix for Soyuz launch pad; Ariane 6 aims high

South Korean rocket startup Innospace is poised to debut a new nano-launcher.

The fifth Ariane 6 rocket climbs away from Kourou, French Guiana, with two European Galileo navigation satellites. Credit: ESA-CNES-Arianespace

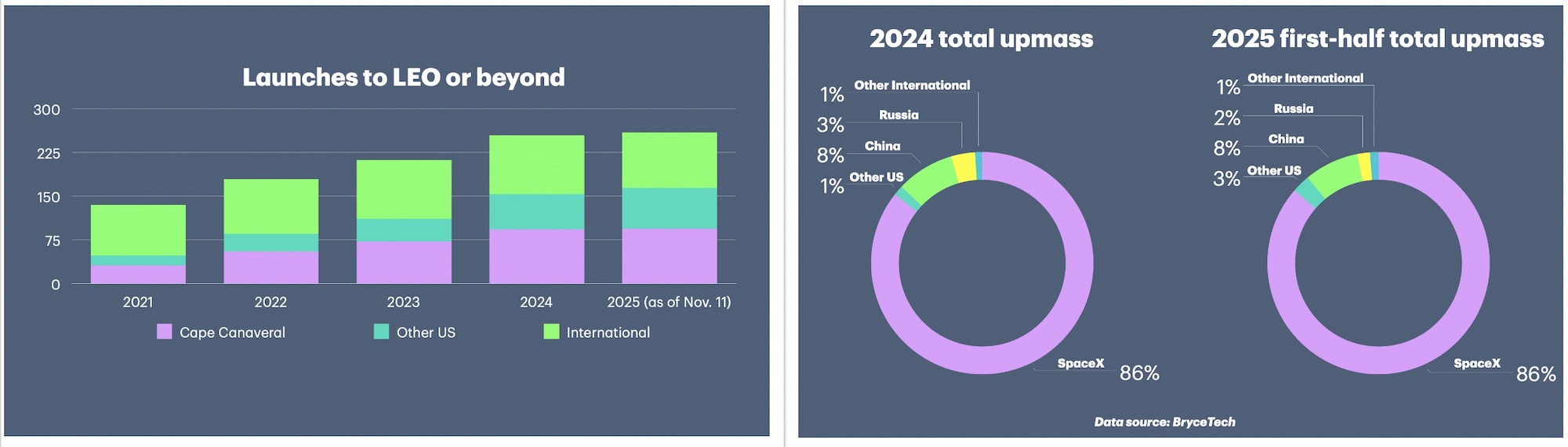

Welcome to Edition 8.23 of the Rocket Report! Several new rockets made their first flights this year. Blue Origin’s New Glenn was the most notable debut, with a successful inaugural launch in January followed by an impressive second flight in November, culminating in the booster’s first landing on an offshore platform. Second on the list is China’s Zhuque-3, a partially reusable methane-fueled rocket developed by the quasi-commercial launch company LandSpace. The medium-lift Zhuque-3 successfully reached orbit on its first flight earlier this month, and its booster narrowly missed landing downrange. We could add China’s Long March 12A to the list if it flies before the end of the year. This will be the final Rocket Report of 2025, but we’ll be back in January with all the news that’s fit to lift.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Rocket Lab delivers for Space Force and NASA. Four small satellites rode a Rocket Lab Electron launch vehicle into orbit from Virginia early Thursday, beginning a government-funded technology demonstration mission to test the performance of a new spacecraft design, Ars reports. The satellites were nestled inside a cylindrical dispenser on top of the 59-foot-tall (18-meter) Electron rocket when it lifted off from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility. A little more than an hour later, the rocket’s upper stage released the satellites one at a time at an altitude of about 340 miles (550 kilometers). The launch was the starting gun for a proof-of-concept mission to test the viability of a new kind of satellite called DiskSats, designed by the Aerospace Corporation.

Stack ’em high… “DiskSat is a lightweight, compact, flat disc-shaped satellite designed for optimizing future rideshare launches,” the Aerospace Corporation said in a statement. The DiskSats are 39 inches (1 meter) wide, about twice the diameter of a New York-style pizza, and measure just 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) thick. Made of composite carbon fiber, each satellite carries solar cells, control avionics, reaction wheels, and an electric thruster to change and maintain altitude. The flat design allows DiskSats to be stacked one on top of the other for launch. The format also has significantly more surface area than other small satellites with comparable mass, making room for more solar cells for high-power missions or large-aperture payloads like radar imaging instruments or high-bandwidth antennas. NASA and the US Space Force cofunded the development and launch of the DiskSat demo mission.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

SpaceX warns of dangerous Chinese launch. China’s recent deployment of nine satellites occurred dangerously close to a Starlink satellite, SpaceX’s vice president of Starlink engineering said. Michael Nicolls wrote in a December 12 social media post that there was a 200-meter close approach between a satellite launched December 10 on a Chinese Kinetica-1 rocket and SpaceX’s Starlink-6079 spacecraft at 560 kilometers (348 miles) altitude, Aviation Week and Space Technology reports. “Most of the risk of operating in space comes from the lack of coordination between satellite operators—this needs to change,” Nicolls wrote.

Blaming the customer... The company in charge of the Kinetica-1 rocket, CAS Space, responded to Nicolls’ post on X saying it would “work on identifying the exact details and provide assistance.” In a follow-up post on December 13, CAS Space said the close call, if confirmed, occurred nearly 48 hours after the satellite separated from the Kinetica-1 rocket, by which time the launch mission had long concluded. “CAS Space will coordinate with satellite operators to proceed.”

A South Korean startup is ready to fly. Innospace, a South Korean space startup, will launch its independently developed commercial rocket, Hanbit-Nano, as soon as Friday, the Maeil Business Newspaper reports. The rocket will lift off from the Alcântara Space Center in Brazil. The small launcher will attempt to deliver eight small payloads, including five deployable satellites, into low-Earth orbit. The launch was delayed two days to allow time for technicians to replace components of the first stage oxidizer supply cooling system.

Hybrid propulsion… This will be the first launch of Innospace’s Hanbit-Nano rocket. The launcher has two stages and stands 71 feet (21.7 meters) tall with a diameter of 4.6 feet (1.4 meters). Hanbit-Nano is a true micro-launcher, capable of placing up to 200 pounds (90 kilograms) of payload mass into Sun-synchronous orbit. It has a unique design, with hybrid engines consuming a mix of paraffin as the fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer.

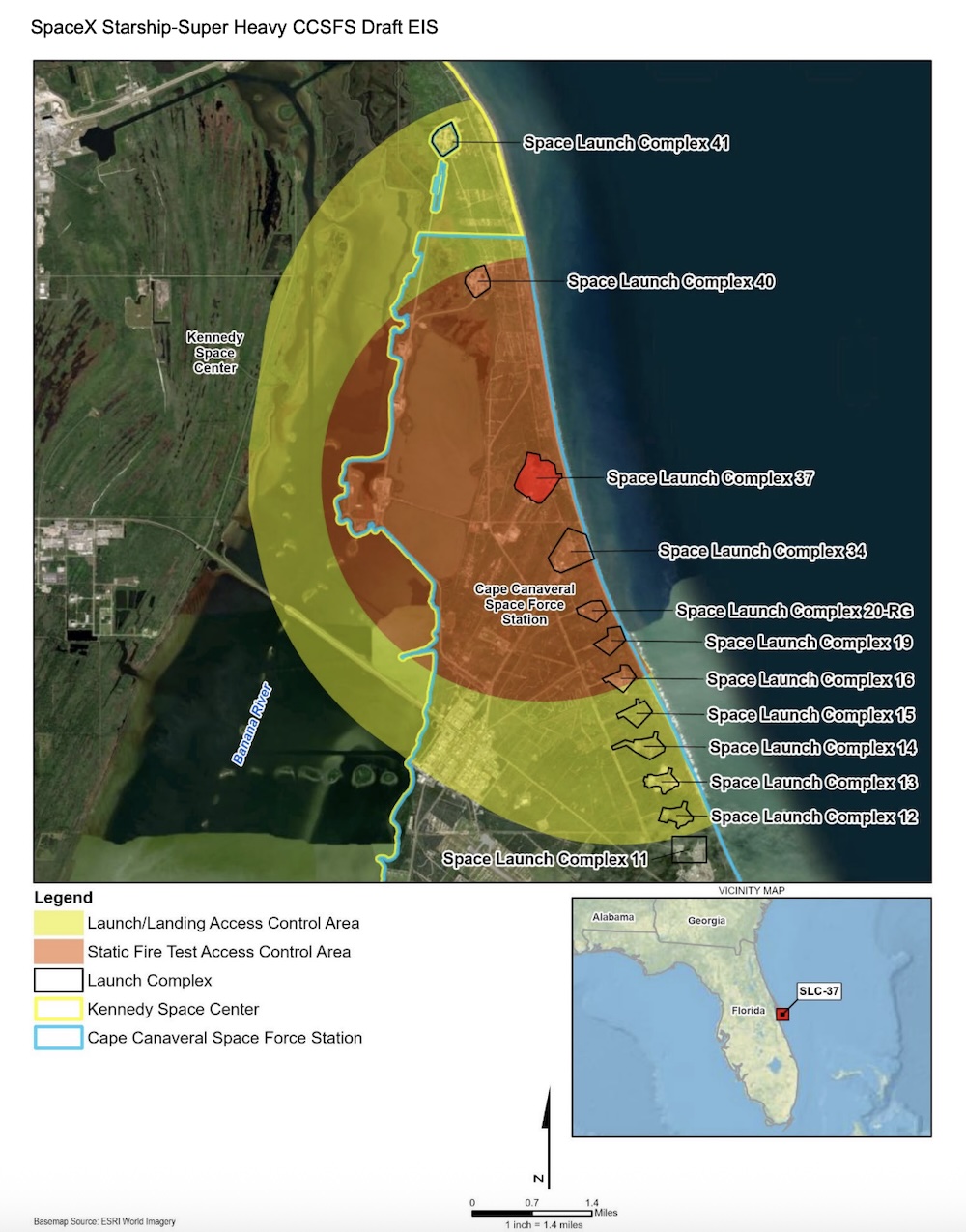

Ten years since a milestone in rocketry. On December 21, 2015, SpaceX launched the Orbcomm-2 mission on an upgraded version of its Falcon 9 rocket. That night, just days before Christmas, the company successfully landed the first stage for the first time. Ars has reprinted a slightly condensed chapter from the book Reentry, authored by Senior Space Editor Eric Berger and published in 2024. The chapter begins in June 2015 with the failure of a Falcon 9 rocket during launch of a resupply mission to the International Space Station and ends with a vivid behind-the-scenes recounting of the historic first landing of a Falcon 9 booster to close out the year.

First-person account… I have my own memory of SpaceX’s first rocket landing. I was there, covering the mission for another publication, as the Falcon 9 lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. In an abundance of caution, Air Force officials in charge of the Cape Canaveral spaceport closed large swaths of the base for the Falcon 9’s return to land. The decision shunted VIPs and media representatives to viewing locations outside the spaceport’s fence, so I joined SpaceX’s official press room at the top of a seven-floor tower near the Port Canaveral cruise terminals. The view was tremendous. We all knew to expect a sonic boom as the rocket came back to Florida, but its arrival was a jolt. The next morning, I joined SpaceX and a handful of reporters and photographers on a chartered boat to get a closer look at the Falcon 9 standing proudly after returning from space.

Roscosmos targets quick fix to Soyuz launch pad. Russian space agency Roscosmos says it expects a damaged launch pad critical to International Space Station operations to be fixed by the end of February, Aviation Week and Space Technology reports. “Launch readiness: end of February 2026,” Roscosmos said in a statement Tuesday. Russia had been scrambling to assess the extent of repairs needed to Pad 31 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan after the November 27 flight of a Soyuz-2.1a rocket damaged key elements of the infrastructure. The pad is the only one capable of supporting Russian launches to the ISS.

Best-case scenario… A quick repair to the launch pad would be the best-case scenario for Roscosmos. A service structure underneath the rocket was unsecured during the launch of a three-man crew to the ISS last month. The structure fell into the launch pad’s flame trench, leaving the complex without the service cabin technicians use to work on the Soyuz rocket before liftoff. Roscosmos said a “complete service cabin replacement kit” has arrived at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, and more than 130 staff are working in two shifts to implement the repairs. A fix by the end of February would allow Russia to resume cargo flights to the ISS in March.

Atlas V closes out an up-and-down year for ULA. United Launch Alliance aced its final launch of 2025, a predawn flight of an Atlas V rocket Tuesday carrying 27 satellites for Amazon’s recently rebranded Leo broadband Internet service, Spaceflight Now reports. The rocket flew northeast from Cape Canaveral to place the Amazon Leo satellites into low-Earth orbit. This was ULA’s fourth launch for Amazon’s satellite broadband venture, previously known as Project Kuiper. ULA closes out 2025 with six launches, one more than the company achieved last year. But ULA’s new Vulcan rocket launched just once this year, disappointingly short of the company’s goal to fly Vulcan up to 10 times.

Taking stock of Amazon Leo… This year marked the start of the deployment of Amazon’s operational satellites. There are now 180 Amazon Leo satellites in orbit after Tuesday’s launch, well short of the FCC’s requirement for Amazon to deploy half of its planned 3,232 satellites by July 31, 2026. Amazon won’t meet the deadline, and it’s likely the retail giant will ask government regulators for a waiver or extension to the deadline. Amazon’s factory is hitting its stride producing and delivering Amazon Leo satellites. The real question is launch capacity. Amazon has contracts to launch satellites on ULA’s Atlas V and Vulcan rockets, Europe’s Ariane 6, and Blue Origin’s New Glenn. Early next year, a batch of 32 Amazon Leo satellites will launch on the first flight of Europe’s uprated Ariane 64 rocket from Kourou, French Guiana. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

A good year for Ariane 6. Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket launched four times this year after a debut test flight in 2024. The four successful missions deployed payloads for the French military, Europe’s weather satellite agency, the European Union’s Copernicus environmental monitoring network, and finally, on Wednesday, the European Galileo navigation satellite fleet, Space News reports. This is a strong showing for a new rocket flying from a new launch pad and a faster ramp-up of launch cadence than any medium- or heavy-lift rocket in recent memory. All five Ariane 6 launches to date have used the Ariane 62 configuration with two strap-on solid rocket boosters. The more powerful Ariane 64 rocket, with four strap-on motors, will make its first flight early next year.

Aiming high… This was the first launch using the Ariane 6 rocket’s ability to fly long-duration missions lasting several hours. The rocket’s cryogenic upper stage, with a restartable Vinci engine, took nearly four hours to inject two Galileo navigation satellites into an orbit more than 14,000 miles (nearly 23,000 kilometers) above the Earth. The flight profile put more stress on the Ariane 6 upper stage than any of the rocket’s previous missions, but the rocket released its payloads into an on-target orbit. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

ESA wants to do more with Ariane 6’s kick stage. The European Space Agency plans to adapt a contract awarded to ArianeGroup in 2021 for an Ariane 6 kick stage to cover its evolution into an orbital transfer vehicle, European Spaceflight reports. The original contract was for the development of the Ariane 6’s Astris kick stage, an optional addition for Ariane 6 missions to deploy payloads into multiple orbits or directly inject satellites into geostationary orbit. Last month, ESA’s member states committed approximately 100 million euros ($117 million) to refocus the Astris kick stage into a more capable Orbital Transfer Vehicle (OTV).

Strong support from Germany… ESA’s director of space transportation, Toni Tolker-Nielsen, said the performance of the Ariane 6 OTV will be “well beyond” that of the originally conceived Astris kick stage. The funding commitment obtained during last month’s ESA ministerial council meeting includes strong support from Germany, Tolker-Nielsen said. Under the new timeline, a protoflight mode of the OTV is expected to be ready for ground qualification by the end of 2028, with an inaugural flight following in 2029. (submitted EllPeaTea)

Another Starship clone in China. Every other week, it seems, a new Chinese launch company pops up with a rocket design and a plan to reach orbit within a few years. For a long time, the majority of these companies revealed designs that looked a lot like SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Now, Chinese companies are starting to introduce designs that appear quite similar to SpaceX’s newer, larger Starship rocket, Ars reports. The newest entry comes from a company called “Beijing Leading Rocket Technology.” This outfit took things a step further by naming its vehicle “Starship-1,” adding that the new rocket will have enhancements from AI and is billed as being a “fully reusable AI rocket.”

Starship prime… China has a long history of copying SpaceX. The country’s first class of reusable rockets, which began flying earlier this month, show strong similarities to the Falcon 9 rocket. Now, it’s Starship. The trend began with the Chinese government. In November 2024, the government announced a significant shift in the design of its super-heavy lift rocket, the Long March 9. Instead of the previous design, a fully expendable rocket with three stages and solid rocket boosters strapped to the sides, the country’s state-owned rocket maker revealed a vehicle that mimicked SpaceX’s fully reusable Starship. At least two more companies have announced plans for Starship-like rockets using SpaceX’s chopstick-style method for booster recovery. Many of these launch startups will not grow past the PowerPoint phase, of course.

Next three launches

Dec. 19: Hanbit-Nano | Spaceward | Alcântara Launch Center, Brazil | 18: 45 UTC

Dec. 20: Long March 5 | Unknown Payload | Wenchang Space Launch Site, China | 12: 30 UTC

Dec. 20: New Shepard | NS-37 crew mission | Launch Site One, Texas | 14: 00 UTC

Rocket Report: Russia pledges quick fix for Soyuz launch pad; Ariane 6 aims high Read More »