Space Force officials take secrecy to new heights ahead of key rocket launch

The Vulcan rocket checks off several important boxes for the Space Force. First, it relies entirely on US-made rocket engines. The Atlas V rocket it is replacing uses Russian-built main engines, and given the chilled relations between the two powers, US officials have long desired to stop using Russian engines to power the Pentagon’s satellites into orbit. Second, ULA says the Vulcan rocket will eventually provide a heavy-lift launch capability at a lower cost than the company’s now-retired Delta IV Heavy rocket.

Third, Vulcan provides the Space Force with an alternative to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, which have been the only rockets in their class available to the military since the last national security mission was launched on an Atlas V rocket one year ago.

Col. Jim Horne, mission director for the USSF-106 launch, said this flight marks a “pretty historic point in our program’s history. We officially end our reliance on Russian-made main engines with this launch, and we continue to maintain our assured access to space with at least two independent rocket service companies that we can leverage to get our capabilities on orbit.”

What’s onboard?

The Space Force has only acknowledged one of the satellites aboard the USSF-106 mission, but there are more payloads cocooned inside the Vulcan rocket’s fairing.

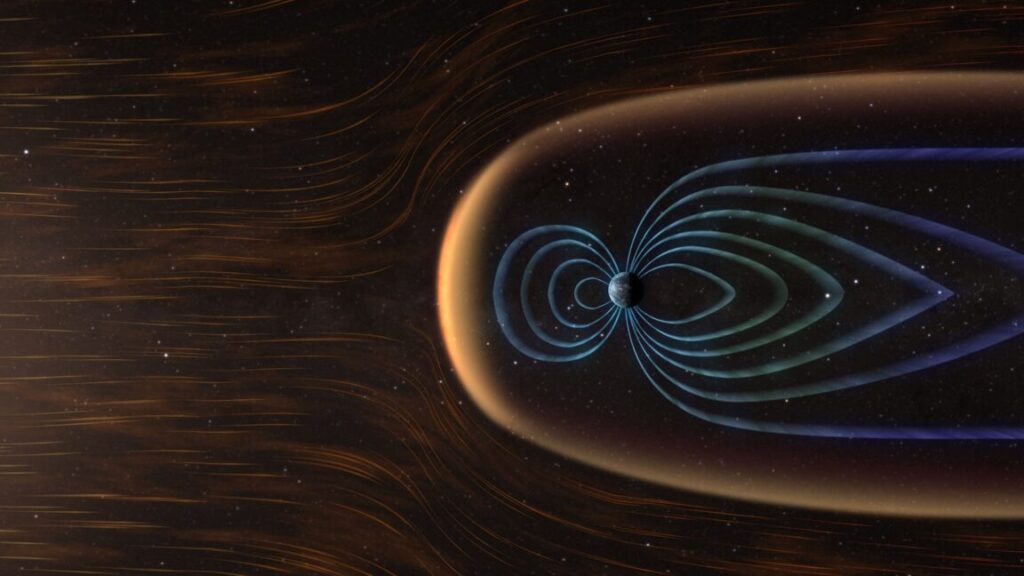

The $250 million mission that officials are willing to talk about is named Navigation Technology Satellite-3, or NTS-3. This experimental spacecraft will test new satellite navigation technologies that may eventually find their way on next-generation GPS satellites. A key focus for engineers who designed and will operate the NTS-3 satellite is to look at ways of overcoming GPS jamming and spoofing, which can degrade satellite navigation signals used by military forces, commercial airliners, and civilian drivers.

“We’re going to be doing, we anticipate, over 100 different experiments,” said Joanna Hinks, senior research aerospace engineer at the Air Force Research Laboratory’s space vehicles directorate, which manages the NTS-3 mission. “Some of the major areas we’re looking at—we have an electronically steerable phased array antenna so that we can deliver higher power to get through interference to the location that it’s needed.”

Arlen Biersgreen, then-program manager for the NTS-3 satellite mission at the Air Force Research Laboratory, presents a one-third scale model of the NTS-3 spacecraft to an audience in 2022. Credit: US Air Force/Andrea Rael

GPS jamming is especially a problem in and near war zones. Investigators probing the crash of Azerbaijan Airlines Flight 8243 last December determined GPS jamming, likely by Russian military forces attempting to counter a Ukrainian drone strike, interfered with the aircraft’s navigation as it approached its destination in the Russian republic of Chechnya. Azerbaijani government officials blamed a Russian surface-to-air missile for damaging the aircraft, ultimately leading to a crash in nearby Kazakhstan that killed 38 people.

“We have a number of different advanced signals that we’ve designed,” Hinks said. “One of those is the Chimera anti-spoofing signal… to protect civil users from spoofing that’s affecting so many aircraft worldwide today, as well as ships.”

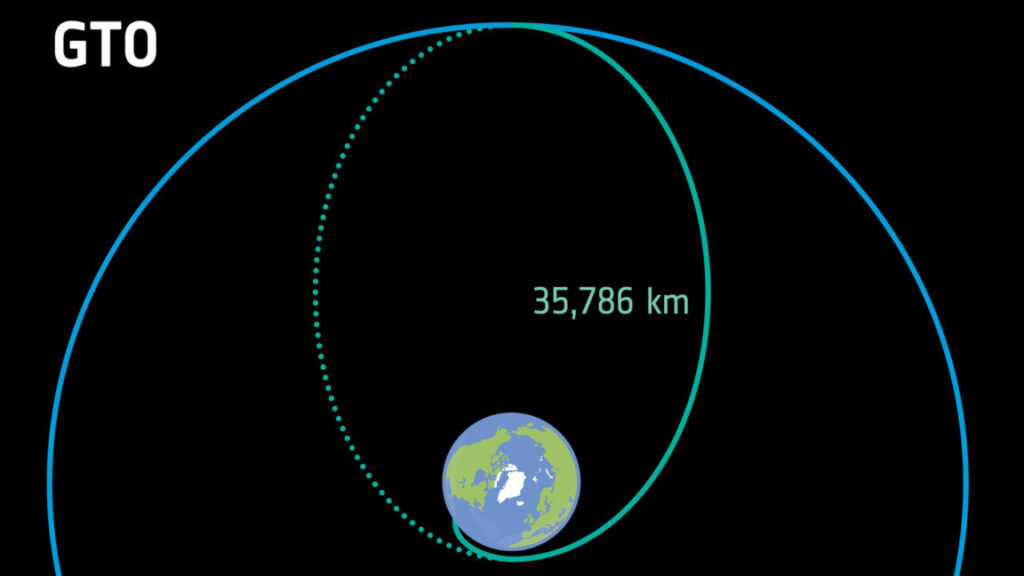

The NTS-3 spacecraft, developed by L3Harris and Northrop Grumman, only takes up a fraction of the Vulcan rocket’s capacity. The satellite weighs less than 3,000 pounds (about 1,250 kilograms), about a quarter of what this version of the Vulcan rocket can deliver to geosynchronous orbit.

Space Force officials take secrecy to new heights ahead of key rocket launch Read More »