US spy satellite agency declassifies high-flying Cold War listening post

The National Reconnaissance Office, the agency overseeing the US government’s fleet of spy satellites, has declassified a decades-old program used to eavesdrop on the Soviet Union’s military communication signals.

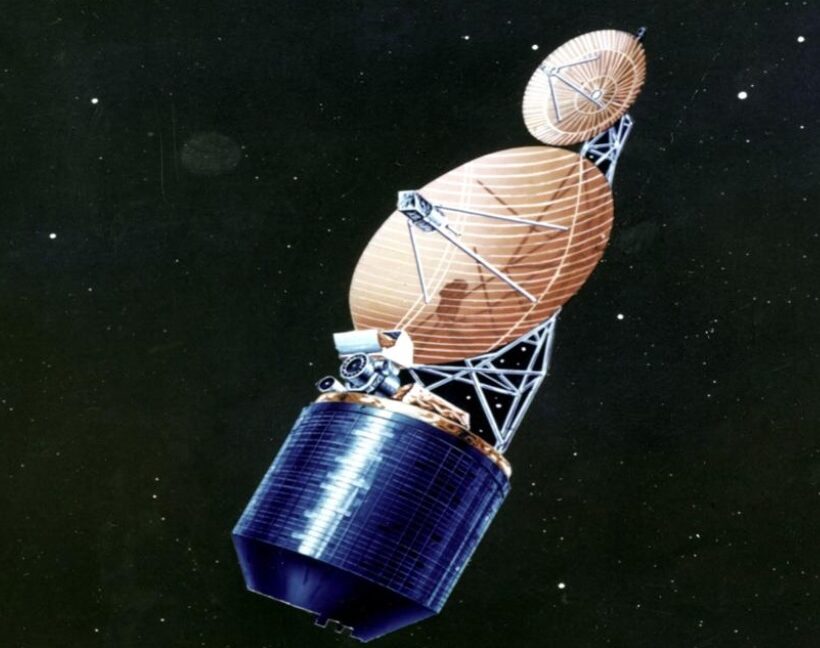

The program was codenamed Jumpseat, and its existence was already public knowledge through leaks and contemporary media reports. What’s new is the NRO’s description of the program’s purpose and development and pictures of the satellites themselves.

In a statement, the NRO called Jumpseat “the United States’ first-generation, highly elliptical orbit (HEO) signals-collection satellite.”

Scooping up signals

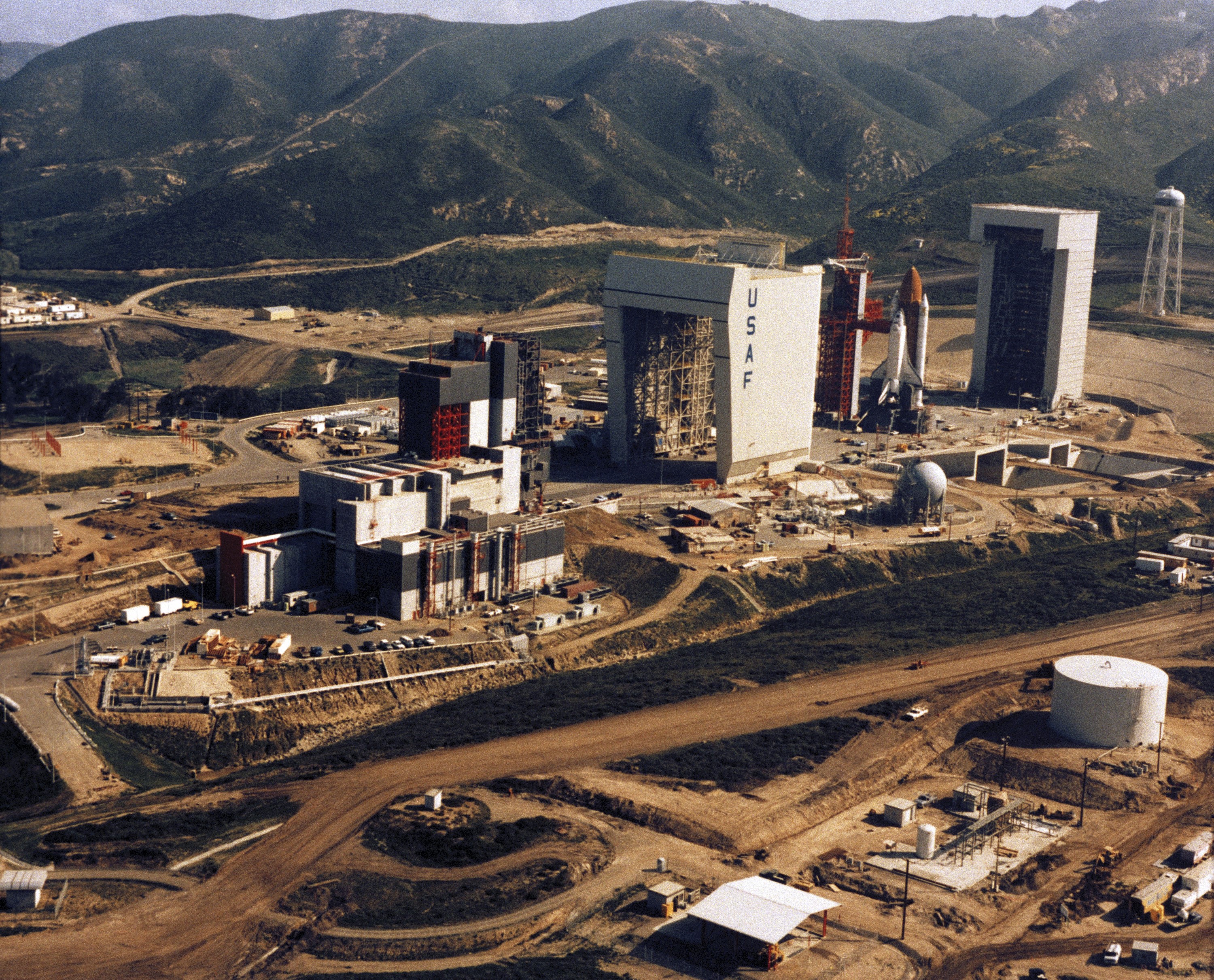

Eight Jumpseat satellites launched from 1971 through 1987, when the US government considered the very existence of the National Reconnaissance Office a state secret. Jumpseat satellites operated until 2006. Their core mission was “monitoring adversarial offensive and defensive weapon system development,” the NRO said. “Jumpseat collected electronic emissions and signals, communication intelligence, as well as foreign instrumentation intelligence.”

Data intercepted by the Jumpseat satellites flowed to the Department of Defense, the National Security Agency, and “other national security elements,” the NRO said.

The Soviet Union was the primary target for Jumpseat intelligence collections. The satellites flew in highly elliptical orbits ranging from a few hundred miles up to 24,000 miles (39,000 kilometers) above the Earth. The satellites’ flight paths were angled such that they reached apogee, the highest point of their orbits, over the far Northern Hemisphere. Satellites travel slowest at apogee, so the Jumpseat spacecraft loitered high over the Arctic, Russia, Canada, and Greenland for most of the 12 hours it took them to complete a loop around the Earth.

This trajectory gave the Jumpseat satellites persistent coverage over the Arctic and the Soviet Union, which first realized the utility of such an orbit. The Soviet government began launching communication and early warning satellites into the same type of orbit a few years before the first Jumpseat mission launched in 1971. The Soviets called the orbit Molniya, the Russian word for lightning.

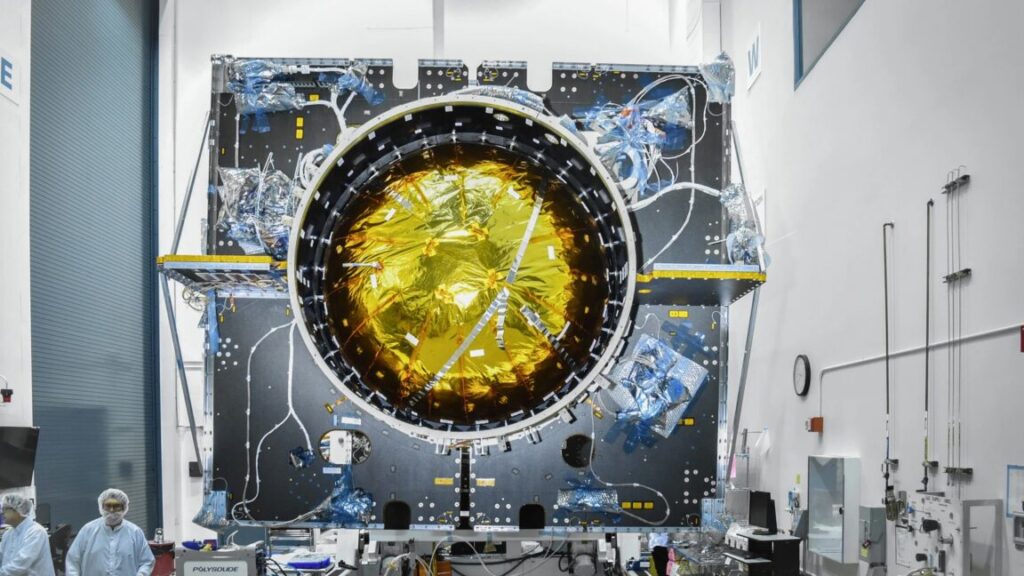

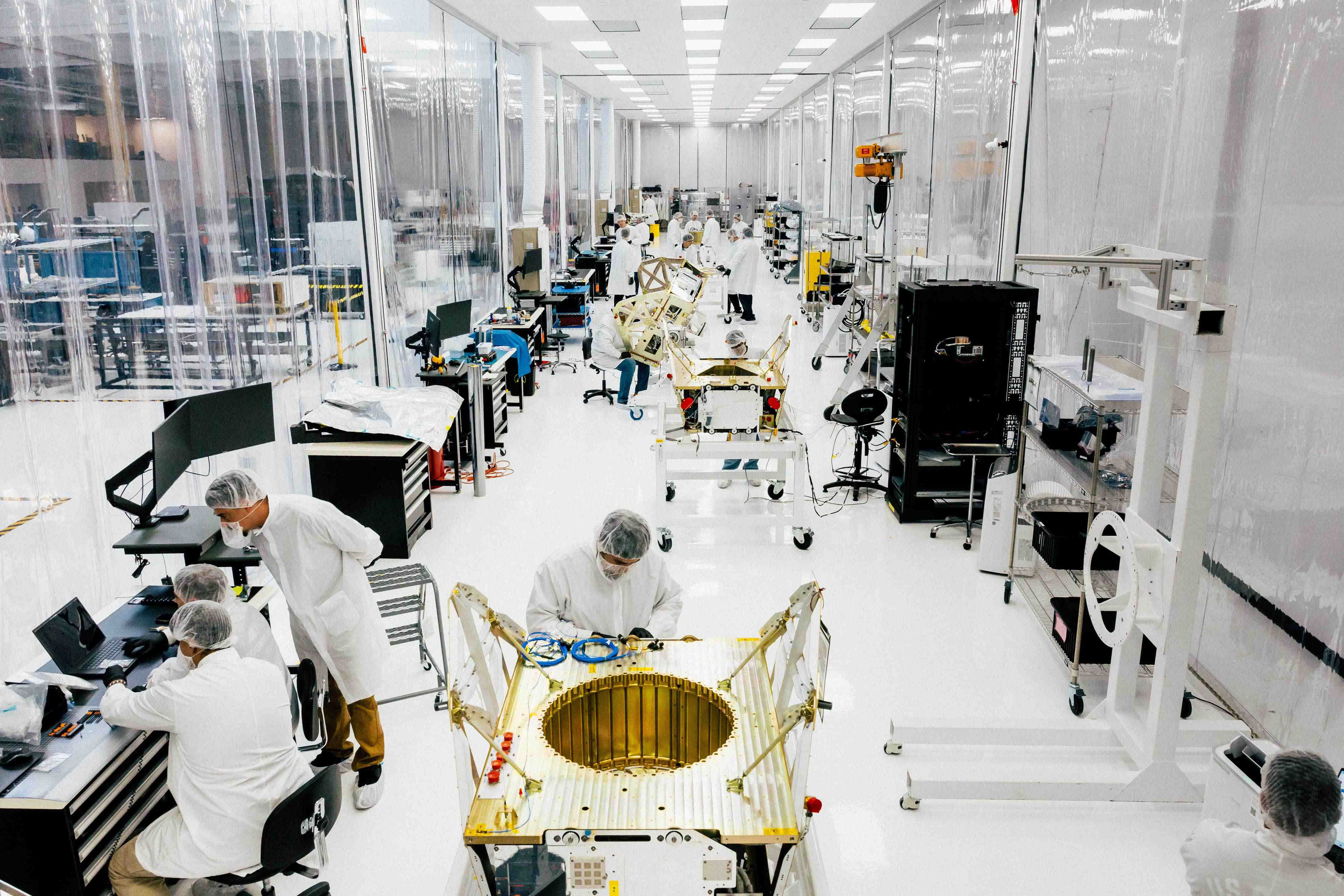

A Jumpseat satellite before launch. Credit: National Reconnaissance Office

The name Jumpseat was first revealed in a 1986 book by the investigative journalist Seymour Hersh on the Soviet Union’s 1983 shoot-down of Korean Air Lines Flight 007. Hersh wrote that the Jumpseat satellites could “intercept all kinds of communications,” including voice messages between Soviet ground personnel and pilots.

US spy satellite agency declassifies high-flying Cold War listening post Read More »