Lawmaker: Trump’s Golden Dome will end the madness, and that’s not a good thing

“The underlying issue here is whether US missile defense should remain focused on the threat from rogue states and… accidental launches, and explicitly refrain from countering missile threats from China or Russia,” DesJarlais said. He called the policy of Mutually Assured Destruction “outdated.”

President Donald Trump speaks alongside Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth in the Oval Office at the White House on May 20, 2025, in Washington, DC. President Trump announced his plans for the Golden Dome, a national ballistic and cruise missile defense system. Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Moulton’s amendment on nuclear deterrence failed to pass the committee in a voice vote, as did another Moulton proposal that would have tapped the brakes on developing space-based interceptors.

But one of Moulton’s amendments did make it through the committee. This amendment, if reconciled with the Senate, would prohibit the Pentagon from developing a privatized or subscription-based missile defense intercept capability. The amendment says the US military can own and operate such a system.

Ultimately, the House Armed Services Committee voted 55–2 to send the NDAA to a vote on the House floor. Then, lawmakers must hash out the differences between the House version of the NDAA with a bill written in the Senate before sending the final text to the White House for President Trump to sign into law.

More questions than answers

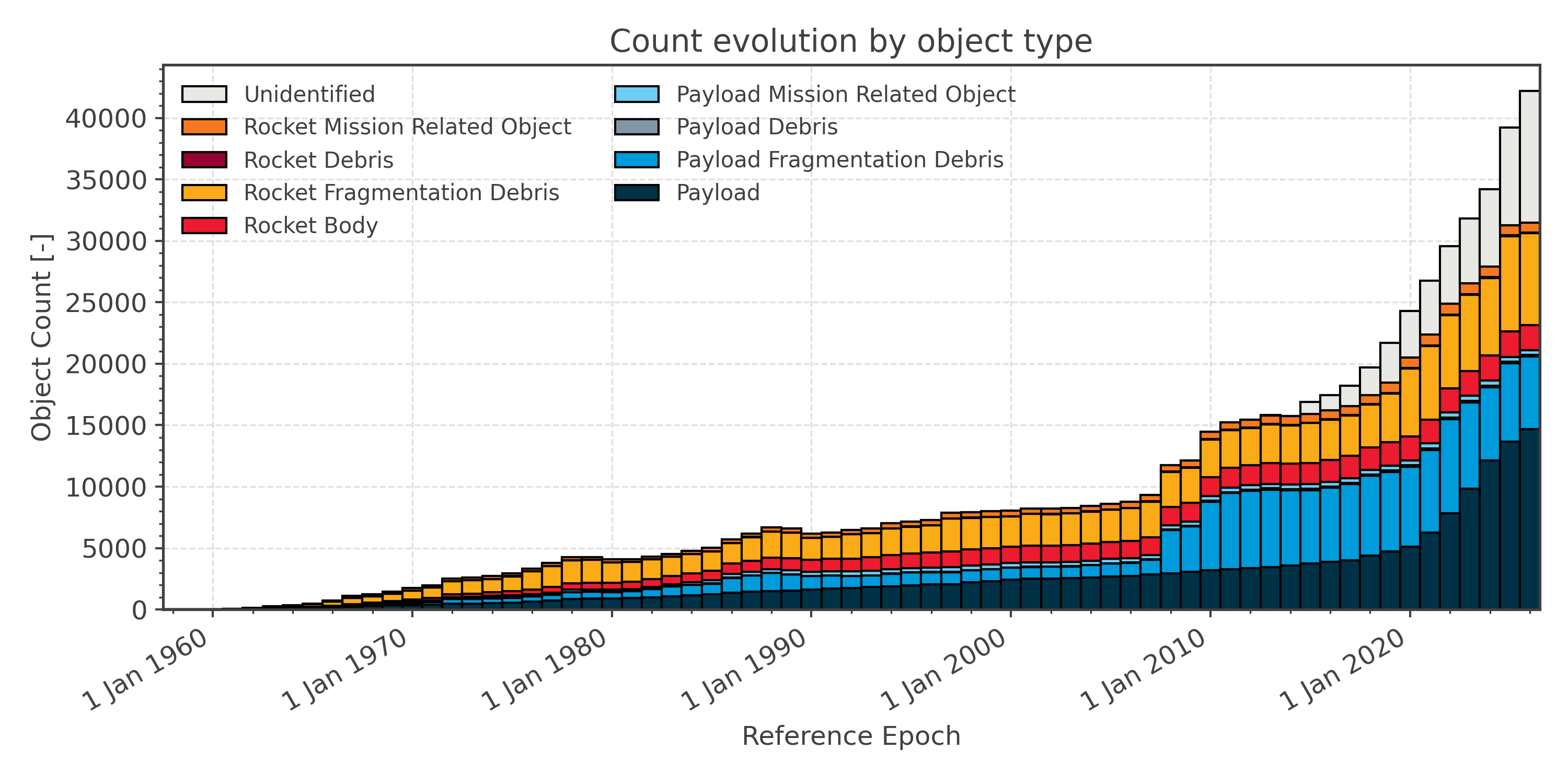

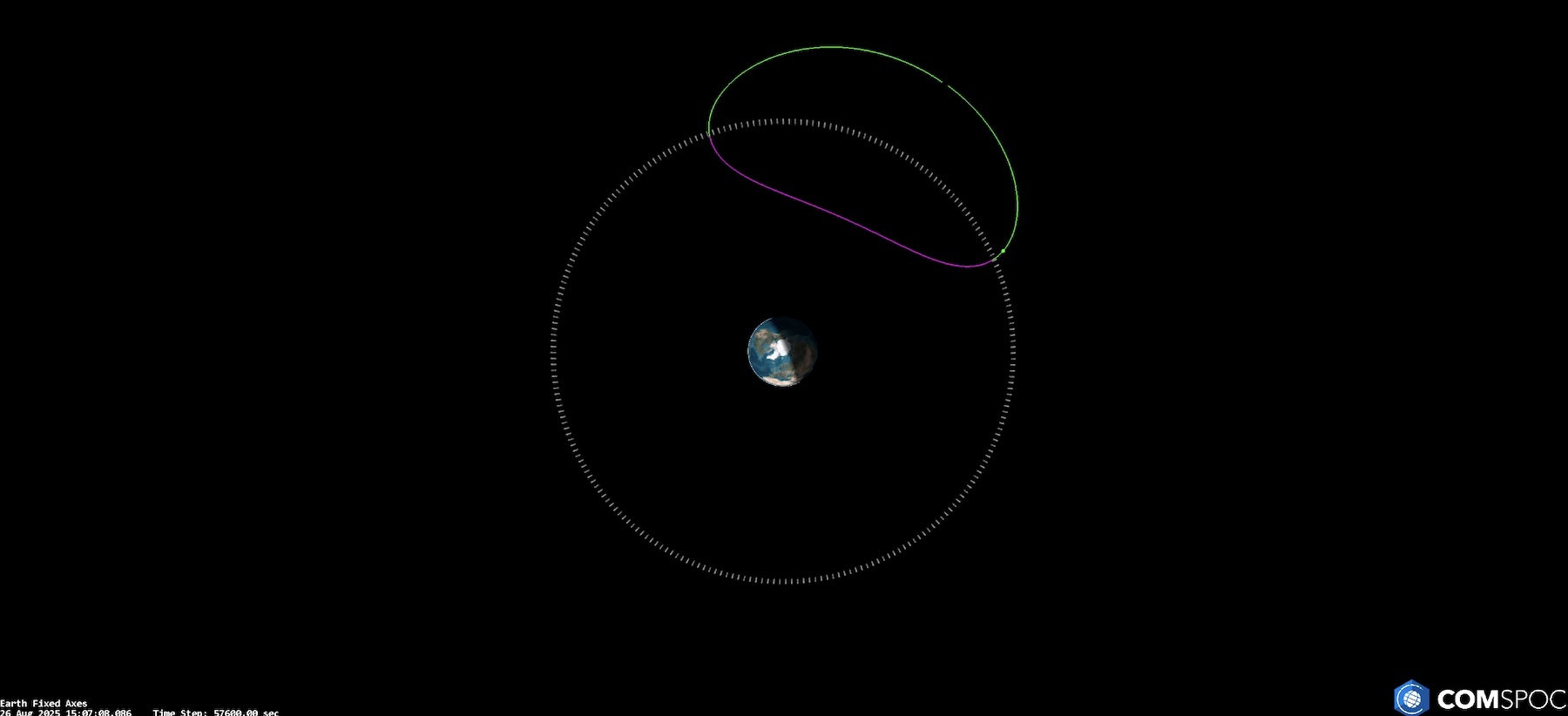

The White House says the missile shield will cost $175 billion over the next three years. But that’s just to start. A network of space-based missile sensors and interceptors, as prescribed in Trump’s executive order, will eventually number thousands of satellites in low-Earth orbit. The Congressional Budget Office reported in May that the Golden Dome program may ultimately cost up to $542 billion over 20 years.

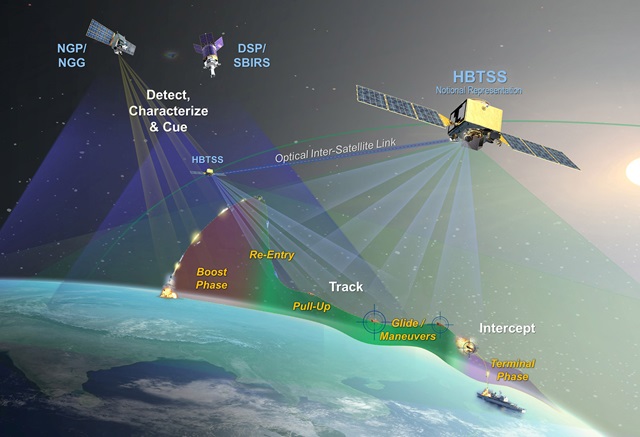

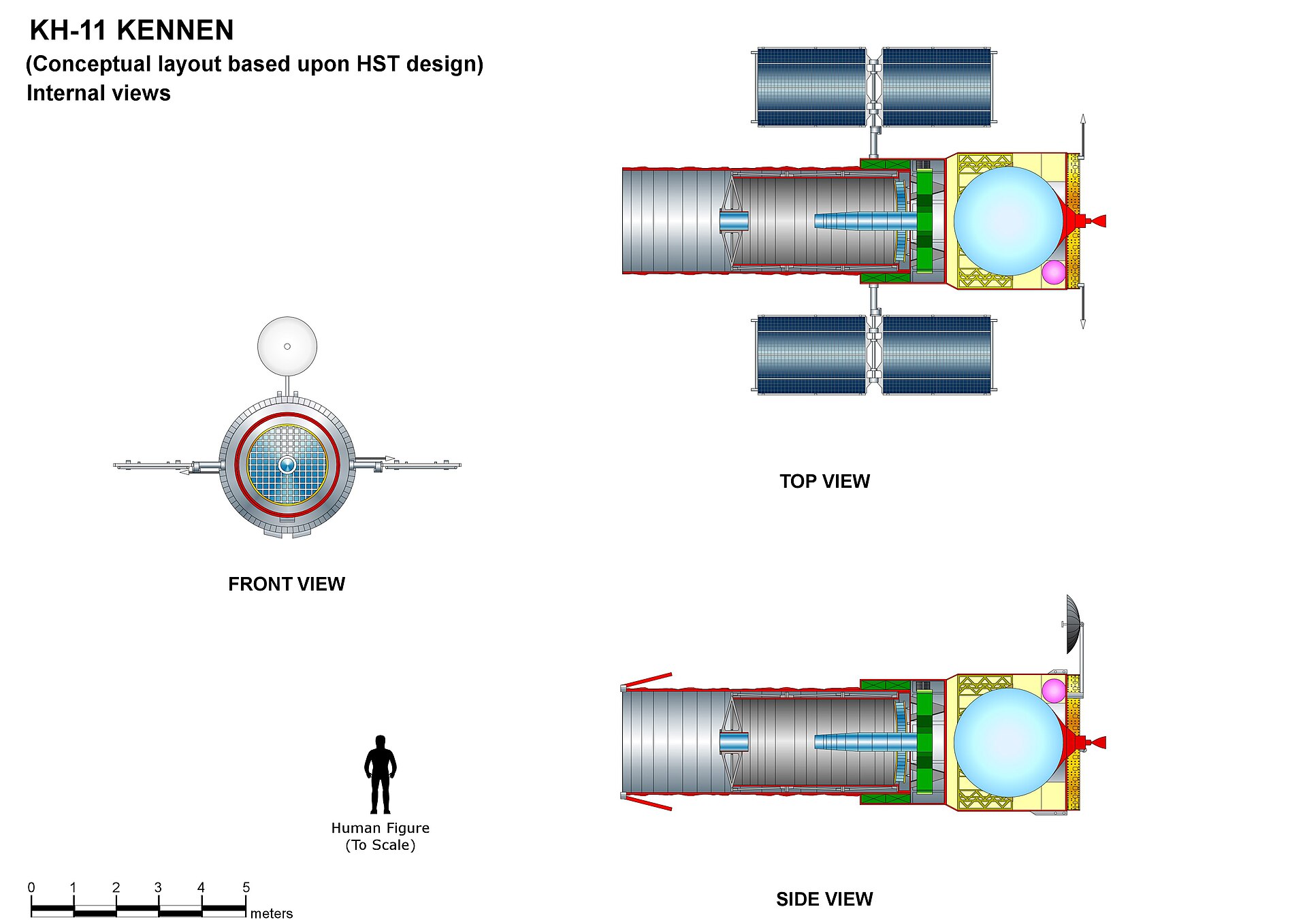

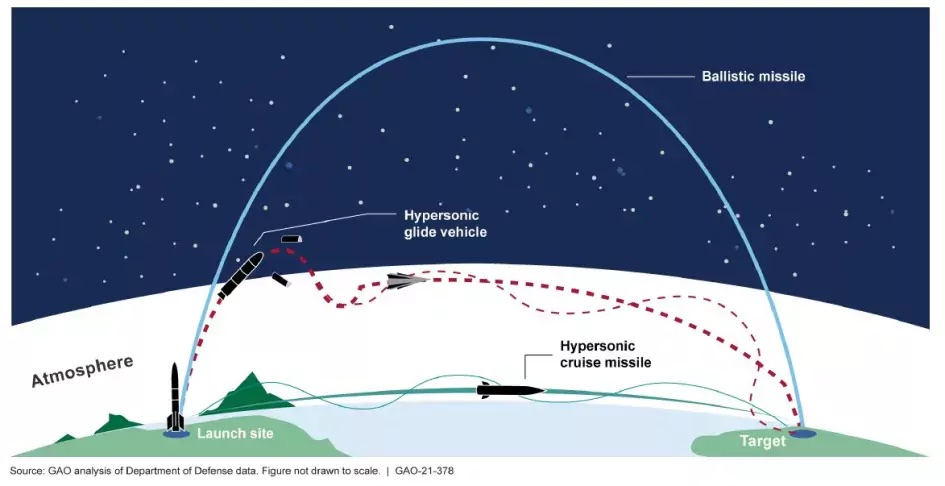

The problem with all of the Golden Dome cost estimates is that the Pentagon has not settled on an architecture. We know the system will consist of a global network of satellites with sensors to detect and track missile launches, plus numerous interceptors in orbit to take out targets in space and during their “boost phase” when they’re moving relatively slowly through the atmosphere.

The Pentagon will order more sea- and ground-based interceptors to destroy missiles, drones, and aircraft as they near their targets within the United States. All of these weapons must be interconnected with a sophisticated command and control network that doesn’t yet exist.

Will Golden Dome’s space-based interceptors use kinetic kill vehicles to physically destroy missiles targeting the United States? Or will the interceptors rely on directed energy weapons like lasers or microwave signals to disable their targets? How many interceptors are actually needed?

These are all questions without answers. Despite the lack of detail, congressional Republicans approved $25 billion for the Pentagon to get started on the Golden Dome program as part of the Trump-backed One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The bill passed Congress with a party-line vote last month.

Israel’s Iron Dome aerial defense system intercepts a rocket launched from the Gaza Strip on May 11, 2021. Credit: Jack Guez/AFP via Getty Images

Moulton earned a bachelor’s degree in physics and master’s degrees in business and public administration from Harvard University. He served as a Marine Corps platoon leader in Iraq and was part of the first company of Marines to reach Baghdad during the US invasion of 2003. Moulton ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020 but withdrew from the race before the first primary contest.

The text of our interview with Moulton is published below. It is lightly edited for length and clarity.

Ars: One of your amendments that passed committee would prevent the DoD from using a subscription or pay-for-service model for the Golden Dome. What prompted you to write that amendment?

Moulton: There were some rumors we heard that this is a model that the administration was pursuing, and there was reporting in mid-April suggesting that SpaceX was partnering with Anduril and Palantir to offer this kind of subscription service where, basically, the government would pay to access the technology rather than own the system. This isn’t an attack on any of these companies or anything. It’s a reassertion of the fundamental belief that these are responsibilities of our government. The decision to engage an intercontinental ballistic missile is a decision that the government must make, not some contractors working at one of these companies.

Ars: Basically, the argument you’re making is that war-fighting should be done by the government and the armed forces, not by contractors or private companies, right?

Moulton: That’s right, and it’s a fundamental belief that I’ve had for a long time. I was completely against contractors in Iraq when I was serving there as a younger Marine, but I can’t think of a place where this is more important than when you’re talking about nuclear weapons.

Ars: One of the amendments that you proposed, but didn’t pass, was intended to reaffirm the nation’s strategy of nuclear deterrence. What was the purpose of this amendment?

Moulton: Let’s just start by saying this is fundamentally why we have to have a theory that forms a foundation for spending hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars. Golden Dome has no clear design, no real cost estimate, and no one has explained how this protects or enhances strategic stability. And there’s a lot of evidence that it would make strategic stability worse because our adversaries would no longer have confidence in Mutual Assured Destruction, and that makes them potentially much more likely to initiate a strike or overreact quickly to some sort of confrontation that has the potential to go nuclear.

In the case of the Russians, it means they could activate their nuclear weapon in space and just take out our Golden Dome interceptors if they think we might get into a nuclear exchange. I mean, all these things are horrific consequences.

Like I said in our hearing, there are two explanations for Golden Dome. The first is that every nuclear theorist for the last 75 years was wrong, and thank God, Donald Trump came around and set us right because in his first administration and every Democratic and Republican administration, we’ve all been wrong—and really the future of nuclear deterrence is nuclear defeat through defense and not Mutually Assured Destruction.

The other explanation, of course, is that Donald Trump decided he wants the golden version of something his friend has. You can tell me which one’s more likely, but literally no one has been able to explain the theory of the case. It’s dangerous, it’s wasteful… It might be incredibly dangerous. I’m happy to be convinced that Golden Dome is the right solution. I’m happy to have people explain why this makes sense and it’s a worthwhile investment, but literally nobody has been able to do that. If the Russians attack us… we know that this system is not going to be 100 percent effective. To me, that doesn’t make a lot of sense. I don’t want to gamble on… which major city or two we lose in a scenario like that. I want to prevent a nuclear war from happening.

Several Chinese DF-5B intercontinental ballistic missiles, each capable of delivering up to 10 independently maneuverable nuclear warheads, are seen during a parade in Beijing on September 3, 2015. Credit: Xinhua/Pan Xu via Getty Images

Ars: What would be the way that an administration should propose something like the Golden Dome? Not through an executive order? What process would you like to see?

Moulton: As a result of a strategic review and backed up by a lot of serious theory and analysis. The administration proposes a new solution and has hearings about it in front of Congress, where they are unafraid of answering tough questions. This administration is a bunch of cowards who can who refuse to answer tough questions in Congress because they know they can’t back up their president’s proposals.

Ars: I’m actually a little surprised we haven’t seen any sort of architecture yet. It’s been six months, and the administration has already missed a few of Trump’s deadlines for selecting an architecture.

Moulton: It’s hard to develop an architecture for something that doesn’t make sense.

Ars: I’ve heard from several retired military officials who think something like the Golden Dome is a good idea, but they are disappointed in the way the Trump administration has approached it. They say the White House hasn’t stated the case for it, and that risks politicizing something they view as important for national security.

Moulton: One idea I’ve had is that the advent of directed energy weapons (such as lasers and microwave weapons) could flip the cost curve and actually make defense cheaper than offense, whereas in the past, it’s always been cheaper to develop more offensive capabilities rather than the defensive means to shoot at them.

And this is why the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in the early 1970s was so effective, because there was this massive arms race where we were constantly just creating a new offensive weapon to get around whatever defenses our adversary proposed. The reason why everyone would just quickly produce a new offensive weapon before that treaty was put into place is because it was easy to do.

My point is that I’ve even thrown them this bone, and I’m saying, ‘Here, maybe that’s your reason, right?” And they just look at me dumbfounded because obviously none of them are thinking about this. They’re just trying to be lackeys for the president, and they don’t recognize how dangerous that is.

Ars: I’ve heard from a chorus of retired and even current active duty military leaders say the same thing about directed energy weapons. You essentially can use one platform in space take take numerous laser shots at a missile instead of expending multiple interceptors for one kill.

Moulton: Yes, that’s basically the theory of the case. Now, my hunch is that if you actually did the serious analysis, you would determine that it still decreases state strategic stability. So in terms of the overall safety and security of the United States, whether it’s directed energy weapons or kinetic interceptors, it’s still a very bad plan.

But I’m even throwing that out there to try to help them out here. “Maybe this is how you want to make your case.” And they just look at me like deer in the headlights because, obviously, they’re not thinking about the national security of the United States.

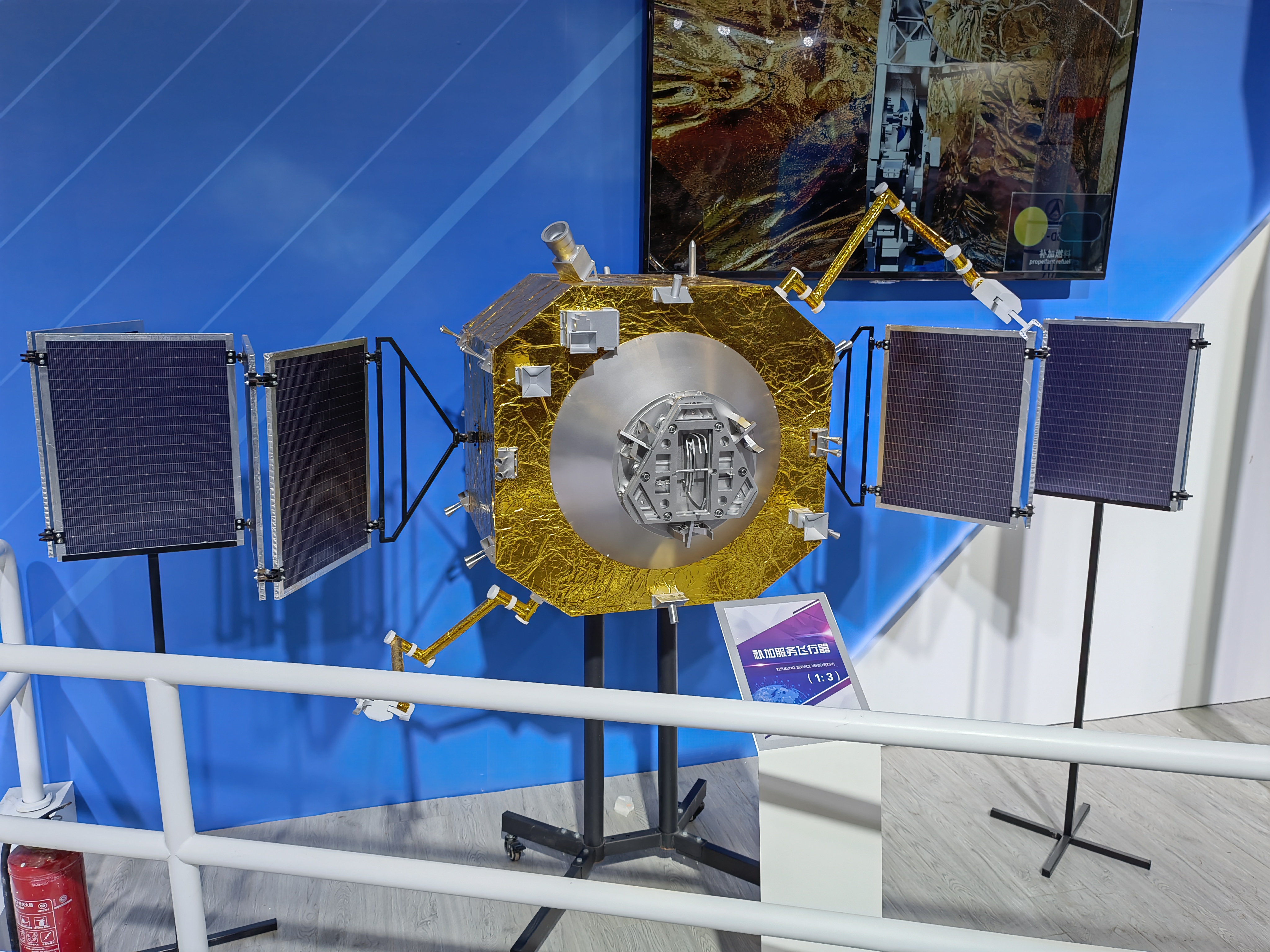

Ars: I also wanted to ask about the Space Force’s push to develop weapons to use against other satellites in orbit. They call these counter-space capabilities. They could be using directed energy, jamming, robotic arms, anti-satellite missiles. This could take many different forms, and the Space Force, for the first time, is talking more openly about these issues. Are these kinds of weapons necessary, in your view, or are they too destabilizing?

Moulton: I certainly wish we could go back to a time when the Russians and Chinese were not developing space weapons—or were not weaponizing space, I should say, because that was the international agreement. But the reality of the world we live in today is that our adversaries are violating that agreement. We have to be prepared to defend the United States.

Ars: Are there any other space policy issues on your radar or things you have concerns about?

Moulton: There’s a lot. There’s so much going on with space, and that’s the reason I chose this subcommittee, even though people would expect me to serve on the subcommittee dealing with the Marine Corps, because I just think space is incredibly important. We’re dealing with everything from promotion policy in the Space Force to acquisition reform to rules of engagement, and anything in between. There’s an awful lot going on there, but I do think that one of the most important things to talk about right now is how dangerous the Golden Dome could be.

Lawmaker: Trump’s Golden Dome will end the madness, and that’s not a good thing Read More »