Trade wars muzzle allied talks on Trump’s Golden Dome missile shield

“International partners, I have not been allowed to talk to yet because of the trade wars.”

President Donald Trump speaks in the Oval Office at the White House on May 20, 2025. Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Gen. Michael Guetlein, the senior officer in charge of the US military’s planned Golden Dome missile defense shield, has laid out an audacious schedule for deploying a network of space-based sensors and interceptors by the end of President Donald Trump’s term in the White House.

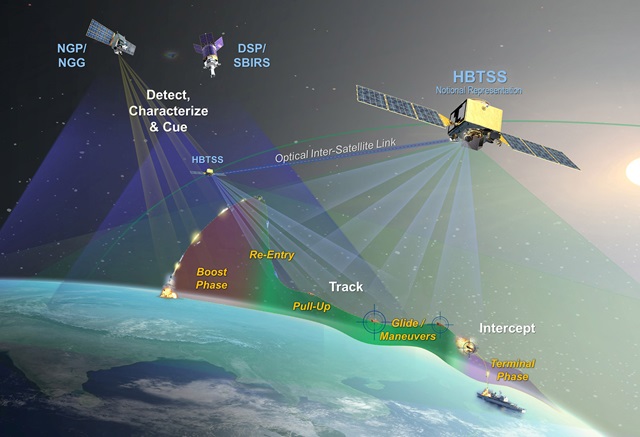

The three-year timeline is aggressive, with little margin for error in the event of budget or technological setbacks. The shield is designed to defend the US homeland against a range of long-range weapons, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), cruise missiles, and newer threats like hypersonic weapons and drones.

“By the summer of ’28, we will be able to defend the entire nation against ballistic missiles, as well as other generation aerial threats, and we will continue to grow that architecture through 2035,” Guetlein said Friday in a presentation to representatives from the US defense industry.

Supporters of Golden Dome say it is necessary to defend the United States against emerging threats from potential adversaries like Russia and China, each of which has a vast arsenal of ballistic missiles and more maneuverable hypersonic missiles that are difficult to detect and even harder to track and shoot down. Critics cite Golden Dome’s high cost and its potential to disrupt the global order, an eventuality they say would make the US homeland more prone to attack.

Guetlein’s team is moving fast in many areas. The Pentagon has inked deals with companies to develop prototypes for space-based missile interceptors, and Golden Dome is underpinned by billions of dollars of preexisting investment in sensor technology, reusable launchers, and mass-produced satellites.

These investments give Golden Dome a head start that former President Ronald Reagan’s similarly scoped Strategic Defense Initiative lacked in the 1980s. The initiative, nicknamed “Star Wars,” was drastically downsized as the Cold War wound down and the government struggled with ballooning costs and technical roadblocks.

Consequences to the chaos

But progress in at least one important area has stalled on the Golden Dome program. The Pentagon will need cooperation, if not tangible contributions, from allies to create the best possible version of the missile defense shield. Fundamentally, it comes down to geography. Places like the Canadian Arctic and Greenland are well-positioned to detect incoming missiles coming over the horizon from Russia or China. They might also be useful for hosting next-gen ground-based interceptors, which today are based in Alaska and California.

Guetlein said his interactions with allies have been limited. It’s the consequence of another of the Trump administration’s core policies: tariffs.

“International partners, I have not been allowed to talk to yet because of the trade wars,” Guetlein said. “The administration wants to get all that laying flat before I start having conversations with our allied partners. But everything we are doing is allied by design.”

Without detailed discussions with allies, the Pentagon’s Golden Dome appears to be one-sided.

“We are already planning on how to integrate our allied partners into our architecture,” Guetlein said. [We’re] already understanding what they can bring to the fight, whether that be capability, whether that be through FMS (foreign military sales), or whether that be territory that we need to access to put sensors, or what have you.”

Canada and Denmark, which count Greenland as an autonomous territory, are longtime allies of the United States. Both nations are members of NATO, and Canada is part of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), an organization whose mission is already aligned with that of the Golden Dome. However, the Trump administration has targeted both nations for high tariffs, apparently in a bid to achieve the White House’s trade and security objectives.

Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule Air Base, with the domes of the Thule Tracking Station, is pictured in northern Greenland on October 4, 2023. Credit: Thomas Traasdahl/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images

Trump’s obsession with acquiring Greenland, where the Space Force already has a military base, soured US relations with Denmark over the last year. The White House threatened additional tariffs on Denmark and other European countries until Denmark agreed to sell Greenland to the United States.

Then, after strong European pushback, Trump suddenly reversed course last week at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He withdrew threats to take Greenland by force and announced an unspecified “framework” with NATO for a future deal regarding the island. Trump told CNBC the framework involved partnerships on missile defense and mining: “They’re going to be involved in the Golden Dome, and they’re going to be involved in mineral rights, and so are we.”

In a statement, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen responded to Trump signaling an openness to a “constructive dialogue” on Arctic security, including the Golden Dome, “provided that this is done with respect for our territorial integrity.”

The White House’s backpedaling may have lowered the temperature of US relations with Denmark, at least for now. But Canada is still in Trump’s crosshairs. In a social media post on Friday, Trump claimed Canada was “against” plans to include Greenland in the Golden Dome program. Kirsten Hillman, Canada’s ambassador to the United States, told CBS News she didn’t know what Trump was talking about.

The back-and-forth followed Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s rebuke of Trump’s foreign policy during a speech at Davos last week. In another sign of the withering US-Canada partnership, Trump threatened in a social media post Saturday to impose a 100 percent tariff on Canada if it follows through on a trade deal with China.

Canadian officials last year disclosed they were in talks to participate in the Golden Dome. In an interview with The War Zone published earlier this month, the operational commander of NORAD’s Canadian region advocated for “integrated missile defense” and “ground-based effectors” but said Canada’s role in a space-based layer would be a “political decision.”

“We look at it as Continental Shield,” said Royal Canadian Air Force Maj. Gen. Chris McKenna. “Golden Dome is the US brand on it. From our point of view, it’s great air missile defense and what we will put on the table to defend the continent with. And so I think there are ongoing negotiations between our governments with respect to what the specific investments will be.”

A roadmap to something

Guetlein’s comments on Golden Dome last week were part of an “industry day” hosted by Space Systems Command, the Los Angeles-based unit charged with procurement for most of the Space Force’s major programs. Asked what his top priority is this year, Guetlein said his emphasis is on the shield’s command and control system, the “glue layer” that ties together everything else necessary to make Golden Dome work. His deadline to demonstrate the command-and-control system is this summer.

The kinetic, or hit-to-kill, elements of the missile shield will come next. “In the summer of ’27, I have to integrate the interceptors, and in ’28 I have to demonstrate operational capability that is fielded against credible threats,” Guetlein said.

This would bring some version of Golden Dome into service before President Trump leaves the White House, a timetable used for several other programs, including NASA’s Artemis mission to land astronauts on the Moon. Officials are willing to trade perfection for speed. Guetlein’s intention is to “rapidly get an 85 percent product in the field.”

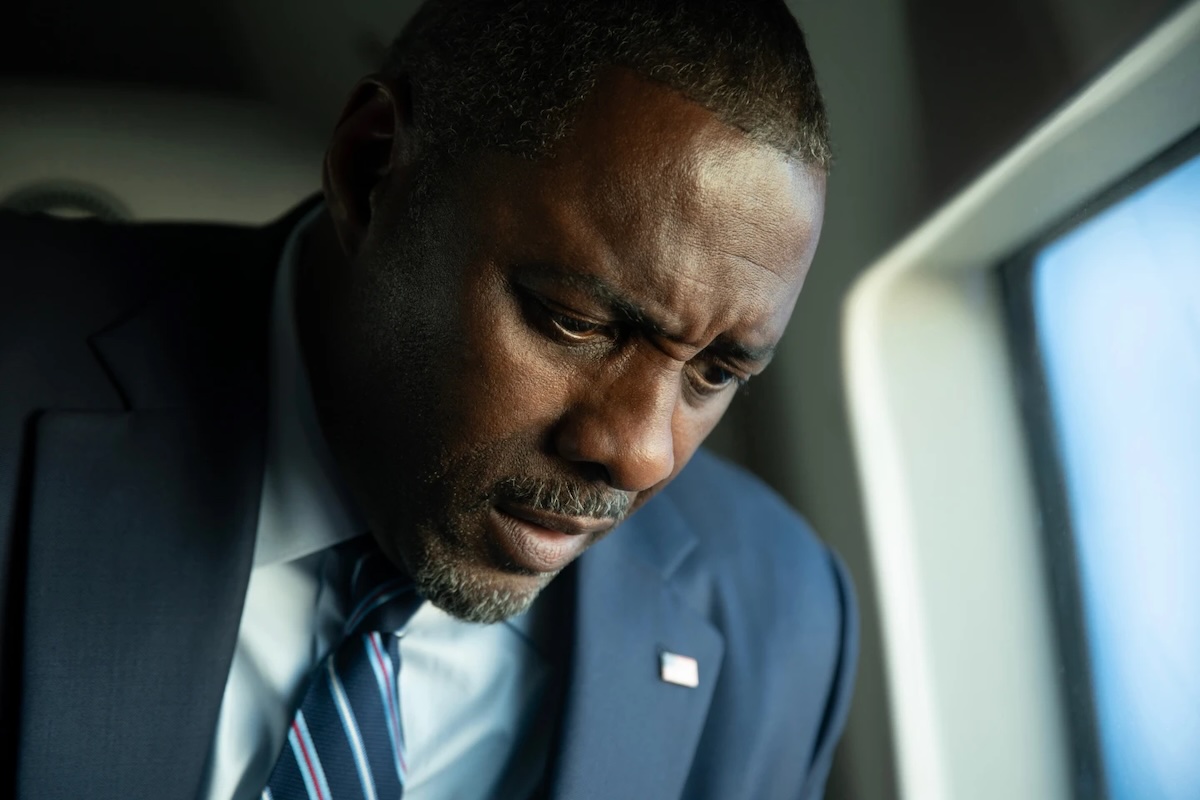

Gen. Michael Guetlein, overseeing the development of the Golden Dome missile defense system, looks on as President Donald Trump speaks in the Oval Office of the White House on May 20, 2025, in Washington, DC. Credit: Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

But a comprehensive missile defense shield, if economically and technically feasible, would take many more years to complete. Some pieces of what could become Golden Dome already exist, such as ground-based midcourse interceptors and an array of missile detection sensors on land, at sea, and in space.

Other elements were well along in development before Trump’s second term in the White House. These include a constellation of low-Earth-orbit satellites to better track hypersonic missiles and relay data to help US and allied forces shoot them down. This network, led by the Space Development Agency, began launching in 2023 but is not yet operational.

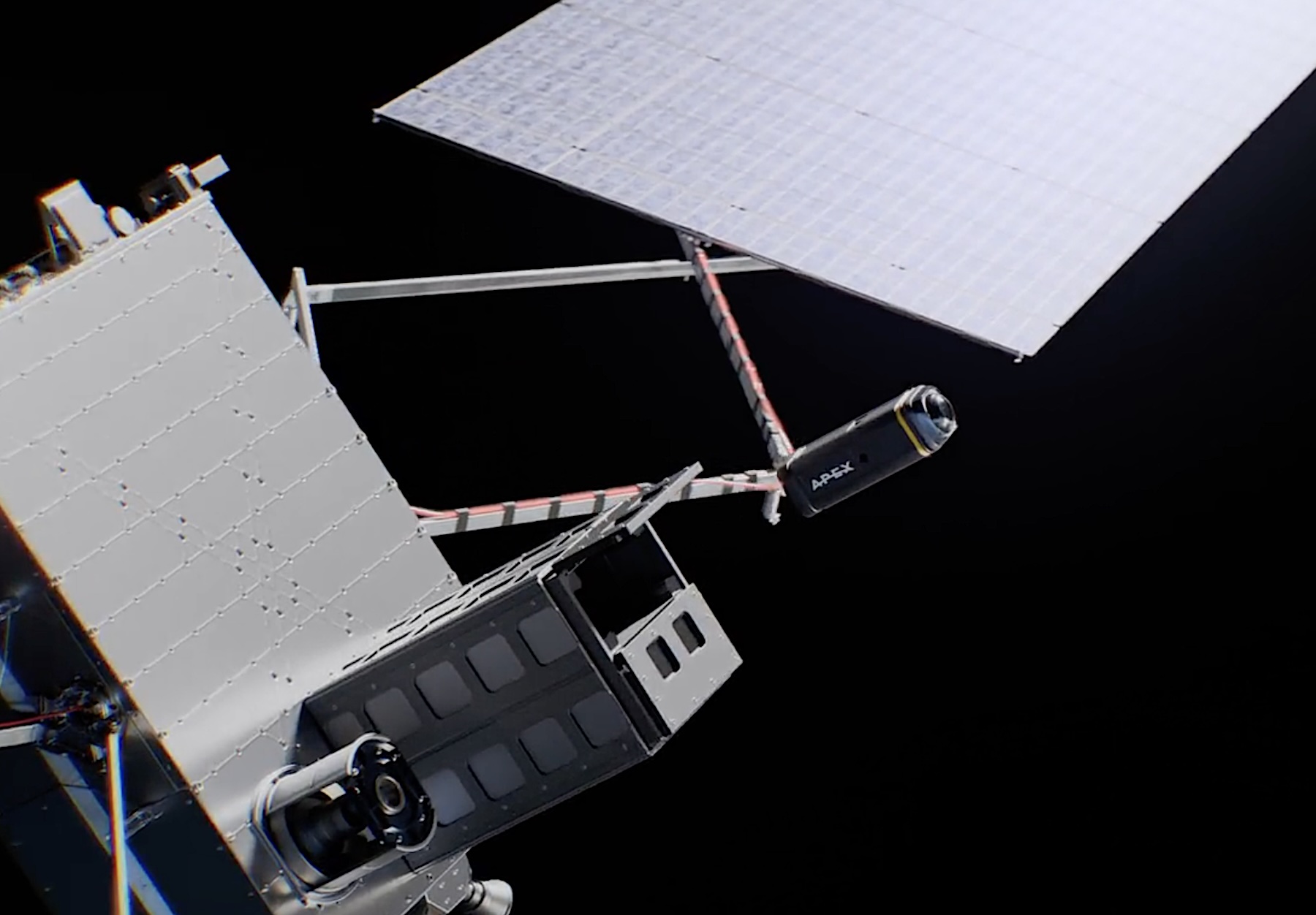

The Pentagon has already kicked off the preliminary steps to buy space-based interceptors. The shield will need hundreds or thousands of orbiting platforms on alert to shoot down a ballistic missile in flight. The Defense Department also aims to field modernized ground-based interceptors and Golden Dome’s command and control network, the system Guetlein identified as his top priority for this year.

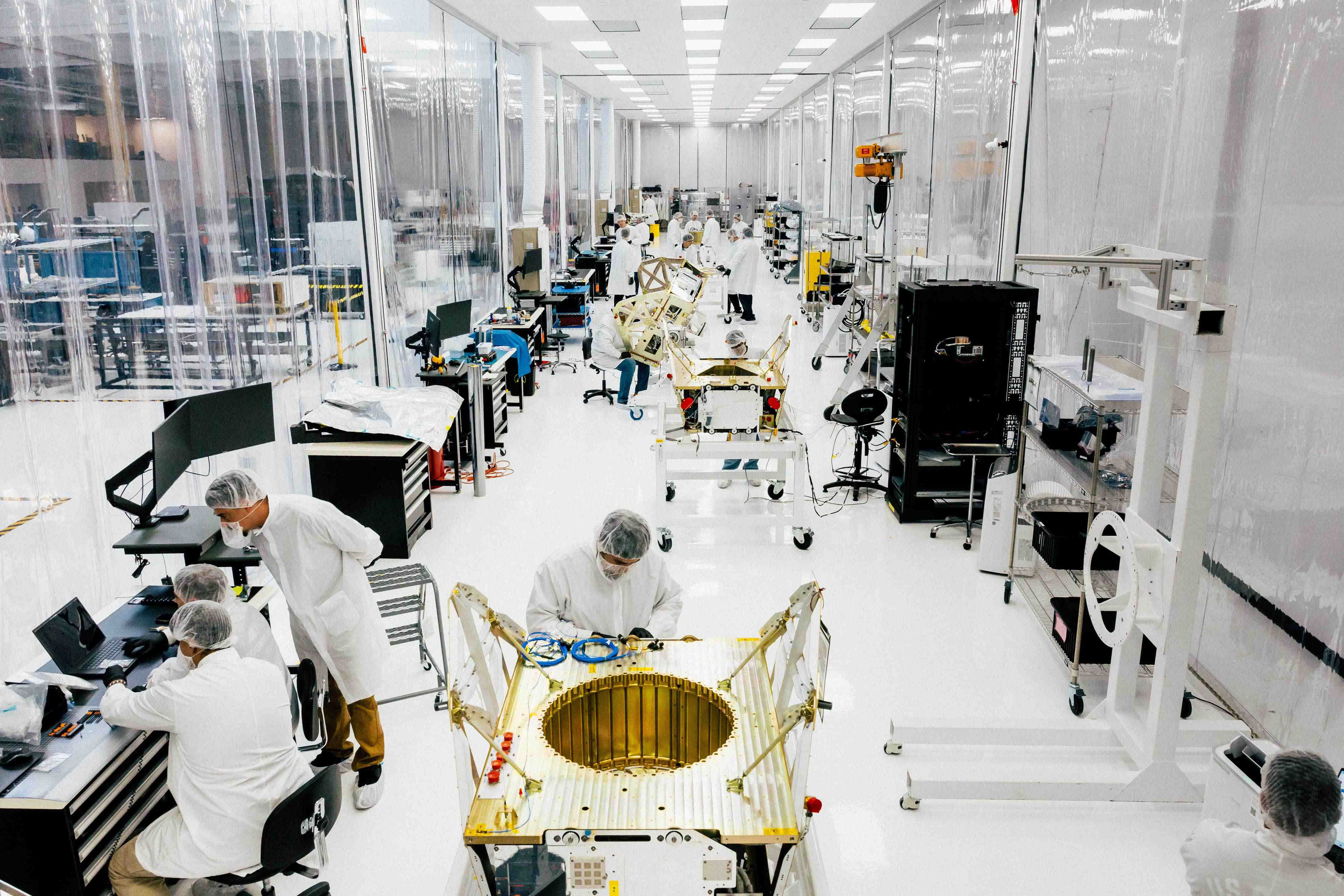

Satellites are getting cheaper and easier to build. SpaceX has manufactured and launched approximately 11,000 Starlink satellites in less than seven years. No other company comes close to this number, but there are businesses looking at building standardized satellites that could be integrated with a range of payloads, including Earth-viewing cameras, radars, communication antennas, or perhaps, a missile interceptor.

But the interceptors themselves are brand new. Nothing like them has ever been put into space and tested before. Last year, the Space Force asked companies to submit their ideas for space-based interceptor (SBI) prototypes. The military awarded 18 companies small prototype development deals in November. The Space Force did not identify the winners, and the value of each contract fell below the $9 million public disclosure threshold for Pentagon programs.

These 18 awards are focused on boost-phase SBIs, weapons that can take out a missile soon after it leaves its silo. From a physics perspective, this is one of the most difficult things to ask an interceptor to do, because the weapon must account for atmospheric disturbances and reentry heating to reach its target. In December, the Space Force issued a follow-up request for prototype proposals looking at space-based midcourse interceptors capable of destroying a ballistic missile while it is coasting through space.

The Pentagon has not said how many SBIs it will need for Golden Dome, or what they will look like. Essentially, an orbiting interceptor will be a flying fuel tank with a rocket and a sensor package to home in on its target. But the Space Force and its prospective Golden Dome contractors, which include industry giants Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin, have not disclosed the interceptors’ design specs or how many the shield will need.

A Standard Missile 3 Block IIA launches from the Aegis Ashore Missile Defense Test Complex at the Pacific Missile Range Facility in Kauai, Hawaii, on December 10, 2018, during a test to intercept an intermediate-range ballistic missile target in space. Credit: Mark Wright/DOD

“I can move money around at will”

Guetlein said Pentagon leaders have empowered him with “unprecedented authorities” on the Golden Dome program. He said Friday his office has full authority over the program’s technical aspects, along with Golden Dome’s procurement, contracting, hiring, security, and budget.

President Trump directed the military to start the Golden Dome program in an executive order last January and nominated Guetlein to head the effort. The Senate confirmed him for the job in a voice vote last July. After the initial pomp of Golden Dome’s announcement, including multiple Oval Office photo ops, military officials went quiet. Guetlein cited security concerns for the Pentagon’s silence on one of Trump’s marquee defense programs.

“I was confirmed on the 18th of July. On the 19th of July, I popped No. 1 on the intel collect list for our adversaries,” Guetlein said. “On the 20th of July, they started hacking our defense industrial base, and the Secretary (of Defense) asked us to go silent. So, we have been quiet. I have not been talking to industry consortiums. I have not been talking to the press. I have not been talking to the think tanks. And it wasn’t until September that I was allowed to even start talking to the Hill (Congress).”

Despite this absence of dialogue, lawmakers approved $23 billion in a down payment for Golden Dome last summer. The final cost of the system is anyone’s guess, but the deployment and sustainment of Golden Dome will certainly cost hundreds of billions of dollars over multiple decades. Just getting the missile shield through a partial activation will cost $175 billion over three years, according to the White House.

Guetlein is off and running with the one-time infusion of $23 billion Congress gave him last year. “The budget authority… for the first $23 billion, it has no strings, no color, no year,” he said. “I can move that money around at will.”

He’s about to receive another $13.4 billion in this year’s defense budget, pending the appropriation bill’s final passage in the Senate and President Trump’s signature.

“I’ve got the Space Force buying SBIs. I’ve got the Army buying munitions and sensors. I’ve got the Navy buying munitions. I’ve got the Missile Defense Agency buying next-generation interceptors, glide phase interceptors, and a whole host of other capabilities,” Guetlein said.

Despite their willingness to fund Golden Dome, lawmakers still aren’t satisfied with the information they are getting from the Pentagon. In a document adjoining this year’s defense budget bill, members of the House and Senate defense appropriations subcommittees wrote they were “unable to effectively assess resources available” and unable to “conduct oversight” of the Golden Dome program “due to insufficient budgetary information” provided by the Department of Defense.

The lawmakers wrote that they “support the operational objectives of Golden Dome” and directed the Pentagon to “provide a comprehensive spend plan” for the missile shield within 60 days of the budget bill becoming law.

“Unfortunately because of the intel threat, we can only brief you at the classified level on what the architecture is,” Guetlein said.

Trade wars muzzle allied talks on Trump’s Golden Dome missile shield Read More »