The $4.3 billion space telescope Trump tried to cancel is now complete

“We’re going to be making 3D movies of what is going on in the Milky Way galaxy.”

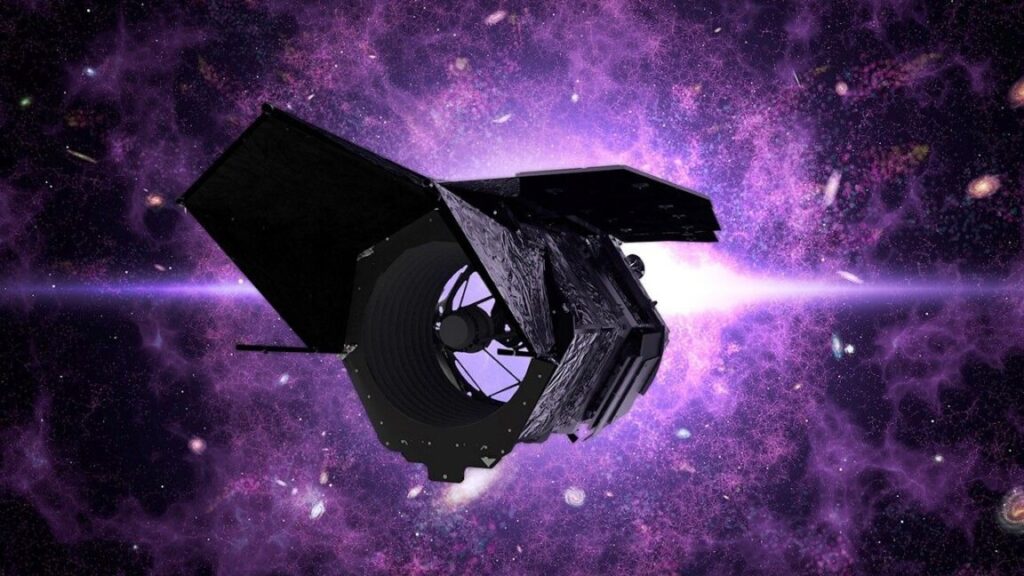

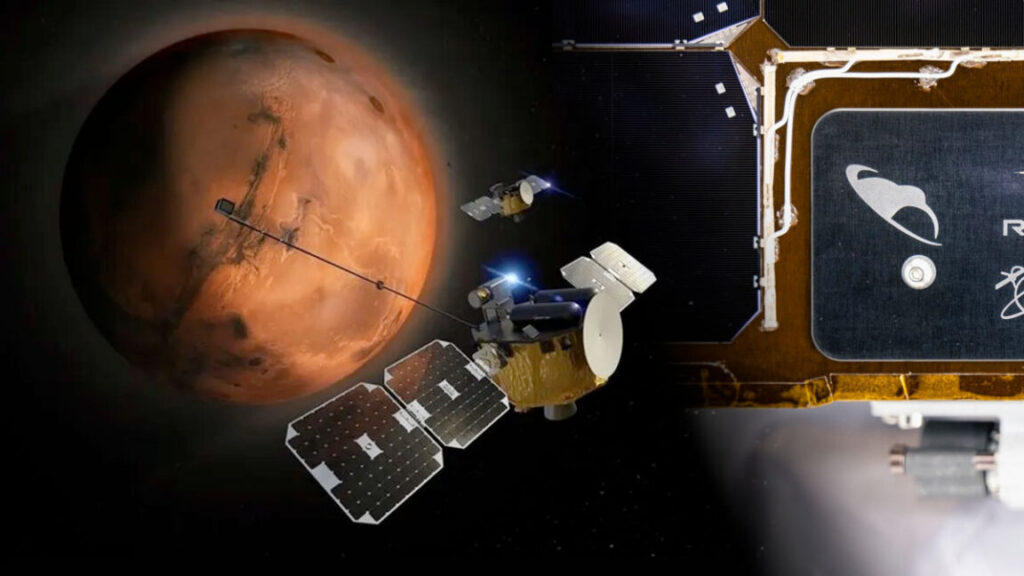

Artist’s concept of the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

A few weeks ago, technicians inside a cavernous clean room in Maryland made the final connection to complete assembly of NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

Parts of this new observatory, named for NASA’s first chief astronomer, recently completed a spate of tests to ensure it can survive the shaking and intense sound of a rocket launch. Engineers placed the core of the telescope inside a thermal vacuum chamber, where it withstood the airless conditions and extreme temperature swings it will see in space.

Then, on November 25, teams at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, joined the inner and outer portions of the Roman Space Telescope. With this milestone, NASA declared the observatory complete and on track for launch as soon as fall 2026.

“The team is ecstatic,” said Jackie Townsend, the observatory’s deputy project manager at Goddard, in a recent interview with Ars. “It has been a long road, but filled with lots of successes and an ordinary amount of challenges, I would say. It’s just so rewarding to get to this spot.”

An ordinary amount of challenges is not something you usually hear a NASA official say about a one-of-a-kind space mission. NASA does hard things, and they usually take more time than originally predicted. Astronomers endured more than 10 years of delays, fixes, and setbacks before the James Webb Space Telescope finally launched in 2021.

Webb is the largest telescope ever put into space. After launch, Webb had to perform a sequence of more than 50 major deployment steps, with 178 release mechanisms that had to work perfectly. Any one of the more than 300 single points of failure could have doomed the mission. In the end, Webb unfolded its giant segmented mirror and delicate sunshield without issue. After a quarter-century of development and more than $11 billion spent, the observatory is finally delivering images and science results. And they’re undeniably spectacular.

The completed Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, seen here with its solar panels deployed inside a clean room at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. Credit: NASA/Jolearra Tshiteya

Seeing far and wide

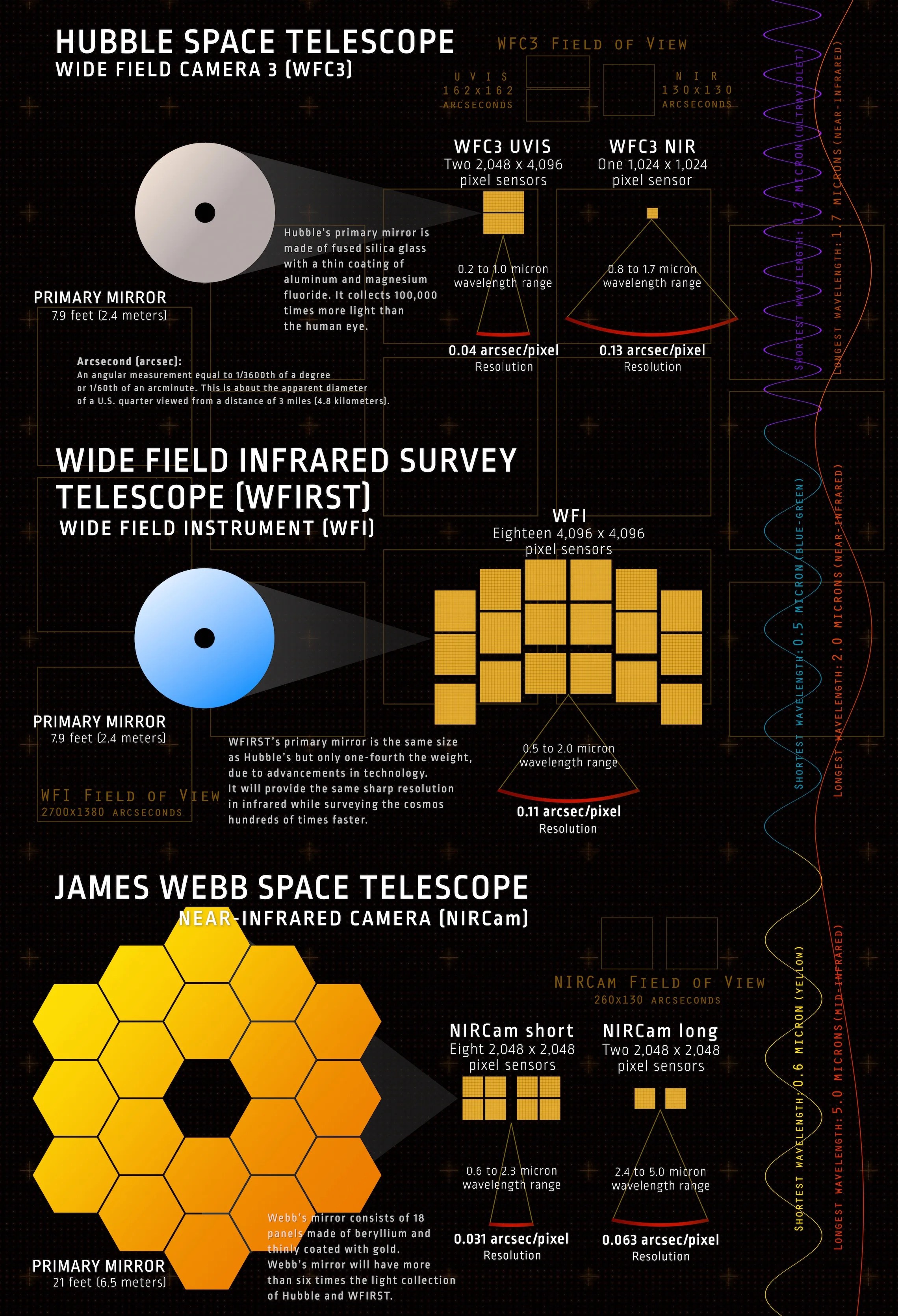

Roman is far less complex, with a 7.9-foot (2.4-meter) primary mirror that is nearly three times smaller than Webb’s. While it lacks Webb’s deep vision, Roman will see wider swaths of the sky, enabling a cosmic census of billions of stars and galaxies near and far (on the scale of the Universe). This broad vision will support research into dark matter and dark energy, which are thought to make up about 95 percent of the Universe. The rest of the Universe is made of regular atoms and molecules that we can see and touch.

It is also illustrative to compare Roman with the Hubble Space Telescope, which has primary mirrors of the same size. This means Roman will produce images with similar resolution to Hubble. The distinction lies deep inside Roman, where technicians have delicately laid an array of detectors to register the faint infrared light coming through the telescope’s aperture.

“Things like night vision goggles will use the same basic detector device, just tuned to a different wavelength,” Townsend said.

These detectors are located in Roman’s Wide Field Instrument, the mission’s primary imaging camera. There are 18 of them, each 4,096×4,096 pixels wide, combining to form a roughly 300-megapixel camera sensitive to visible and near-infrared light. Teledyne, the company that produced the detectors, says this is the largest infrared focal plane ever made.

The near-infrared channel on Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, which covers much the same part of the spectrum as Roman, has a single 1,024-pixel detector.

“That’s how you get to a much higher field-of-view for the Roman Space Telescope, and it was one of the key enabling technologies,” Townsend told Ars. “That was one place where Roman invested significant dollars, even before we started as a mission, to mature that technology so that it was ready to infuse into this mission.”

With these detectors in its bag, Roman will cover much more cosmic real estate than Hubble. For example, Roman will be able to re-create Hubble’s famous Ultra Deep Field image with the same sharpness, but expand it to show countless stars and galaxies over an area of the sky at least 100 times larger.

This infographic illustrates the differences between the sizes of the primary mirrors and detectors on the Hubble, Roman, and Webb telescopes. Credit: NASA

Roman has a second instrument, the Roman Coronagraph, with masks, filters, and adaptive optics to block out the glare from stars and reveal the faint glow from objects around them. It is designed to photograph planets 100 million times fainter than their stars, or 100 to 1,000 times better than similar instruments on Webb and Hubble. Roman can also detect exoplanets using the tried-and-true transit method, but scientists expect the new telescope will find a lot more than past space missions, thanks to its wider vision.

“With Roman’s construction complete, we are poised at the brink of unfathomable scientific discovery,” said Julie McEnery, Roman’s senior project scientist at NASA Goddard, in a press release. “In the mission’s first five years, it’s expected to unveil more than 100,000 distant worlds, hundreds of millions of stars, and billions of galaxies. We stand to learn a tremendous amount of new information about the universe very rapidly after Roman launches.”

Big numbers are crucial for learning how the Universe works, and Roman will feed vast volumes of data down to astronomers on Earth. “So much of what physics is trying to understand about the nature of the Universe today needs large number statistics in order to understand,” Townsend said.

In one of Roman’s planned sky surveys, the telescope will cover in nine months what would take Hubble between 1,000 and 2,000 years. In another survey, Roman will cover an area equivalent to 3,455 full moons in about three weeks, then go back and observe a smaller portion of that area repeatedly over five-and-a-half days—jobs that Hubble and Webb can’t do.

“We will do fundamentally different science,” Townsend said. “In some subset of our observations, we’re going to be making 3D movies of what is going on in the Milky Way galaxy and in distant galaxies. That is just something that’s never happened before.”

Getting here and getting there

Roman’s promised scientific bounty will come at a cost of $4.3 billion, including expenses for development, manufacturing, launch, and five years of operations.

This is about $300 million more than NASA expected when it formally approved Roman for development in 2020, an overrun the agency blamed on complications related to the coronavirus pandemic. Otherwise, Roman’s budget has been stable since NASA officials finalized the mission’s architecture in 2017, when it was still known by a bulky acronym: WFIRST, the Wide Field InfraRed Survey Telescope.

At that time, the agency reclassified the Roman Coronagraph as a technology demonstration, allowing managers to relax their requirements for the instrument and stave off concerns about cost growth.

Roman survived multiple attempts by the first Trump administration to cancel the mission. Each time, Congress restored funding to keep the observatory on track for launch in the mid-2020s. With Donald Trump back in the White House, the administration’s budget office earlier this year again wanted to cancel Roman. Eventually, the Trump administration released its fiscal year 2026 budget request in May, calling for a drastic cut to Roman, but not total cancellation.

Once again, both houses of Congress signaled their opposition to the cuts, and the mission remains on track for launch next year, perhaps as soon as September. This is eight months ahead of the schedule NASA has publicized for Roman for the last few years.

Townsend told Ars the mission escaped the kind of crippling cost overruns and delays that afflicted Webb through careful planning and execution. “Roman was under a cost cap, and we operated to that,” she said. “We went through reasonable efforts to preclude those kinds of highly complex deployments that lead you to having trouble in integration and test.”

The outer barrel section of the Roman Space Telescope inside a thermal vacuum chamber at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Maryland. Credit: NASA/Sydney Rohde

There are only a handful of mechanisms that must work after Roman’s launch. They include a deployable cover designed to shield the telescope’s mirror during launch and solar array wings that will unfold once Roman is in space. The observatory will head to an observing post about a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

“We don’t have moments of terror for the deployment,” Townsend said. “Obviously, launch is always a risk, the tip-off rates that you have when you separate from the launch vehicle… Then, obviously, getting the aperture door open so that it’s deployed is another one. But these feel like normal aerospace risks, not unusual, harrowing moments for Roman.”

It also helps that Roman will use a primary mirror gifted to NASA by the National Reconnaissance Office, the US government’s spy satellite agency. The NRO originally ordered the mirror for a telescope that would peer down on the Earth, but the spy agency no longer needed it. Before NASA got its hands on the surplus mirror in 2012, scientists working on the preliminary design for what became Roman were thinking of a smaller telescope.

The larger telescope will make Roman a more powerful tool for science, and the NRO’s donation eliminated the risk of a problem or delay manufacturing a new mirror. But the upside meant NASA had to build a more massive spacecraft and use a bigger rocket to accommodate it, adding to the observatory’s cost.

Tests of Roman’s components have gone well this year. Work on Roman continued at Goddard through the government shutdown in the fall. On Webb, engineers uncovered one problem after another as they tried to verify the observatory would perform as intended in space. There were leaky valves, tears in the Webb’s sunshield, a damaged transducer, and loose screws. With Roman, engineers so far have found no “significant surprises” during ground testing, Townsend said.

“What we always hope when you’re doing this final round of environmental tests is that you’ve wrung out the hardware at lower levels of assembly, and it looks like, in Roman’s case, we did a spectacular job at the lower level,” she said.

With Roman now fully assembled, attention at Goddard will turn to an end-to-end functional test of the observatory early next year, followed by electromagnetic interference testing, and another round of acoustic and vibration tests. Then, perhaps around June of next year, NASA will ship the observatory to Kennedy Space Center, Florida, to prepare for launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket.

“We’re really down to the last stretch of environmental testing for the system,” Townsend said. “It’s definitely already seen the worst environment until we get to launch.”

The $4.3 billion space telescope Trump tried to cancel is now complete Read More »