Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket came back home after taking aim at Mars

“Never before in history has a booster this large nailed the landing on the second try.”

Blue Origin’s 320-foot-tall (98-meter) New Glenn rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. Credit: Blue Origin

The rocket company founded a quarter-century ago by billionaire Jeff Bezos made history Thursday with the pinpoint landing of an 18-story-tall rocket on a floating platform in the Atlantic Ocean.

The on-target touchdown came nine minutes after the New Glenn rocket, built and operated by Bezos’ company Blue Origin, lifted off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, at 3: 55 pm EST (20: 55 UTC). The launch was delayed from Sunday, first due to poor weather at the launch site in Florida, then by a solar storm that sent hazardous radiation toward Earth earlier this week.

“We achieved full mission success today, and I am so proud of the team,” said Dave Limp, CEO of Blue Origin. “It turns out Never Tell Me The Odds (Blue Origin’s nickname for the first stage) had perfect odds—never before in history has a booster this large nailed the landing on the second try. This is just the beginning as we rapidly scale our flight cadence and continue delivering for our customers.”

The two-stage launcher set off for space carrying two NASA science probes on a two-year journey to Mars, marking the first time any operational satellites flew on Blue Origin’s new rocket, named for the late NASA astronaut John Glenn. The New Glenn hit its marks on the climb into space, firing seven BE-4 main engines for nearly three minutes on a smooth ascent through blue skies over Florida’s Space Coast.

Seven BE-4 engines power New Glenn downrange from Florida’s Space Coast. Credit: Blue Origin

The engines consumed super-cold liquified natural gas and liquid oxygen, producing more than 3.8 million pounds of thrust at full power. The BE-4s shut down, and the first stage booster released the rocket’s second stage, with dual hydrogen-fueled BE-3U engines, to continue the mission into orbit.

The booster soared to an altitude of 79 miles (127 kilometers), then began a controlled plunge back into the atmosphere, targeting a landing on Blue Origin’s offshore recovery vessel named Jacklyn. Moments later, three of the booster’s engines reignited to slow its descent in the upper atmosphere. Then, moments before reaching the Atlantic, the rocket again lit three engines and extended its landing gear, sinking through low-level clouds before settling onto the football field-size deck of Blue Origin’s recovery platform 375 miles (600 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral.

A pivotal moment

The moment of touchdown appeared electric at several Blue Origin facilities around the country, which had live views of cheering employees piped in to the company’s webcast of the flight. This was the first time any company besides SpaceX has propulsively landed an orbital-class rocket booster, coming nearly 10 years after SpaceX recovered its first Falcon 9 booster intact in December 2015.

Blue Origin’s New Glenn landing also came almost exactly a decade after the company landed its smaller suborbital New Shepard rocket for the first time in West Texas. Just like Thursday’s New Glenn landing, Blue Origin successfully recovered the New Shepard on its second-ever attempt.

Blue Origin’s heavy-lifter launched successfully for the first time in January. But technical problems prevented the booster from restarting its engines on descent, and the first stage crashed at sea. Engineers made “propellant management and engine bleed control improvements” to resolve the problems, and the fixes appeared to work Thursday.

The rocket recovery is a remarkable achievement for Blue Origin, which has long lagged dominant SpaceX in the commercial launch business. SpaceX has now logged 532 landings with its Falcon booster fleet. Now, with just a single recovery in the books, Blue Origin sits at second in the rankings for propulsive landings of orbit-class boosters. Bezos’ company has amassed 34 landings of the suborbital New Shepard model, which lacks the size and doesn’t reach the altitude and speed of the New Glenn booster.

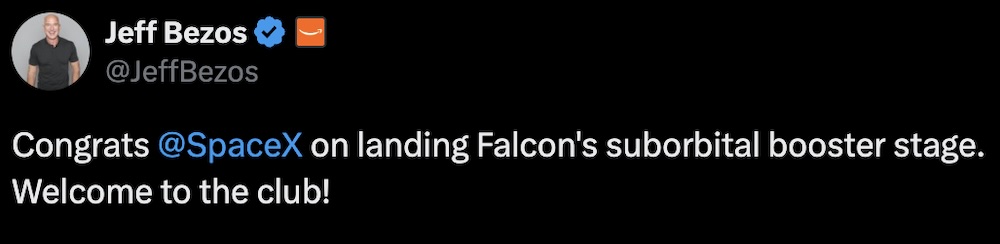

Blue Origin landed a New Shepard returning from space for the first time in November 2015, a few weeks before SpaceX first recovered a Falcon 9 booster. Bezos threw shade on SpaceX with a post on Twitter, now called X, after the first Falcon 9 landing: “Welcome to the club!”

Jeff Bezos, Blue Origin’s founder and owner, wrote this message on Twitter following SpaceX’s first Falcon 9 landing on December 21, 2015. Credit: X/Jeff Bezos

Finally, after Thursday, Blue Origin officials can say they are part of the same reusable rocket club as SpaceX. Within a few days, Blue Origin’s recovery vessel is expected to return to Port Canaveral, Florida, where ground crews will offload the New Glenn booster and move it to a hangar for inspections and refurbishment.

“Today was a tremendous achievement for the New Glenn team, opening a new era for Blue Origin and the industry as we look to launch, land, repeat, again and again,” said Jordan Charles, the company’s vice president for the New Glenn program, in a statement. “We’ve made significant progress on manufacturing at rate and building ahead of need. Our primary focus remains focused on increasing our cadence and working through our manifest.”

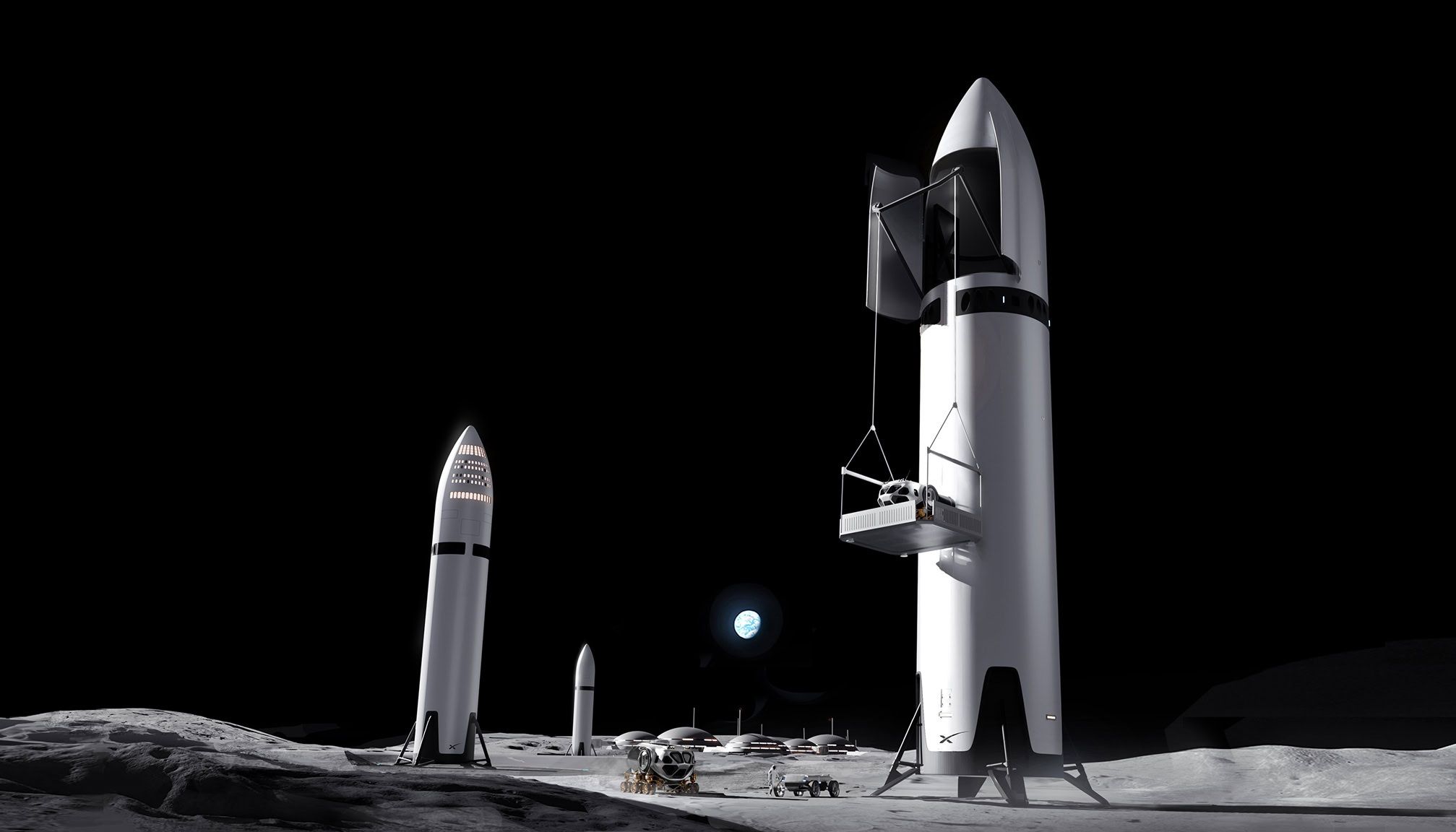

Blue Origin plans to reuse the same booster next year for the first launch of the company’s Blue Moon Mark 1 lunar cargo lander. This mission is currently penciled in to be next on Blue Origin’s New Glenn launch schedule. Eventually, the company plans to have a fleet of reusable boosters, like SpaceX has with the Falcon 9, that can each be flown up to 25 times.

New Glenn is a core element in Blue Origin’s architecture for NASA’s Artemis lunar program. The rocket will eventually launch human-rated lunar landers to the Moon to provide astronauts with rides to and from the surface of the Moon.

The US Space Force will also examine the results of Thursday’s launch to assess New Glenn’s readiness to begin launching military satellites. The military selected Blue Origin last year to join SpaceX and United Launch Alliance as a third launch provider for the Defense Department.

Blue Origin’s New Glenn booster, 23 feet (7 meters) in diameter, on the deck of the company’s landing platform in the Atlantic Ocean.

Slow train to Mars

The mission wasn’t over with the buoyant landing in the Atlantic. New Glenn’s second stage fired its engines twice to propel itself on a course toward deep space, setting up for deployment of NASA’s two ESCAPADE satellites a little more than a half-hour after liftoff.

The identical satellites were released from their mounts on top of the rocket to begin their nearly two-year journey to Mars, where they will enter orbit to survey how the solar wind interacts with the rarefied uppermost layers of the red planet’s atmosphere. Scientists believe radiation from the Sun gradually stripped away Mars’ atmosphere, driving runaway climate change that transitioned the planet from a warm, habitable world to the global inhospitable desert seen today.

“I’m both elated and relieved to see NASA’s ESCAPADE spacecraft healthy post-launch and looking forward to the next chapter of their journey to help us understand Mars’ dynamic space weather environment,” said Rob Lillis, the mission’s principal investigator from the University of California, Berkeley.

Scientists want to understand the environment at the top of the Martian atmosphere to learn more about what drove this change. With two instrumented spacecraft, ESCAPADE will gather data from different locations around Mars, providing a series of multipoint snapshots of solar wind and atmospheric conditions. Another NASA spacecraft, named MAVEN, has collected similar data since arriving in orbit around Mars in 2014, but it is only a single observation post.

ESCAPADE, short for Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers, was developed and launched on a budget of about $80 million, a bargain compared to all of NASA’s recent Mars missions. The spacecraft were built by Rocket Lab, and the project is managed on behalf of NASA by the University of California, Berkeley.

The two spacecraft for NASA’s ESCAPADE mission at Rocket Lab’s factory in Long Beach, California. Credit: Rocket Lab

NASA paid Blue Origin about $20 million for the launch of ESCAPADE, significantly less than it would have cost to launch it on any other dedicated rocket. The space agency accepted the risk of launching on the relatively unproven New Glenn rocket, which hasn’t yet been certified by NASA or the Space Force for the government’s marquee space missions.

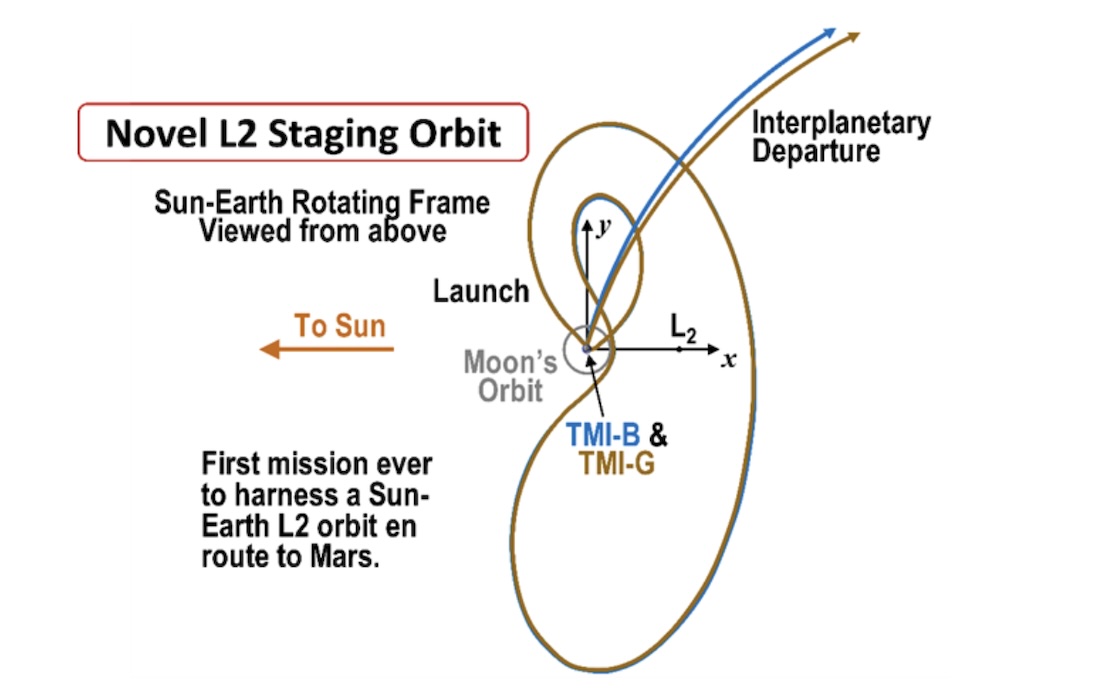

The mission was supposed to launch last year, when Earth and Mars were in the right positions to enable a direct trip between the planets. But Blue Origin delayed the launch, forcing a yearlong wait until the company’s second New Glenn was ready to fly. Now, the ESCAPADE satellites, each about a half-ton in mass fully fueled, will loiter in a unique orbit more than a million miles from Earth until next November, when they will set off for the red planet. ESCAPADE will arrive at Mars in September 2027 and begin its science mission in 2028.

Rocket Lab ground controllers established communication with the ESCAPADE satellites late Thursday night.

“The ESCAPADE mission is part of our strategy to understand Mars’ past and present so we can send the first astronauts there safely,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “Understanding Martian space weather is a top priority for future missions because it helps us protect systems, robots, and most importantly, humans, in extreme environments.”

Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket came back home after taking aim at Mars Read More »