In a win for science, NASA told to use House budget as shutdown looms

The situation with the fiscal year 2026 budget for the United States is, to put it politely, kind of a mess.

The White House proposed a budget earlier this year with significant cuts for a number of agencies, including NASA. In the months since then, through the appropriations process, both the House and Senate have proposed their own budget templates. However, Congress has not passed a final budget, and the new fiscal year begins on October 1.

As a result of political wrangling over whether to pass a “continuing resolution” to fund the government before a final budget is passed, a government shutdown appears to be increasingly likely.

Science saved, sort of

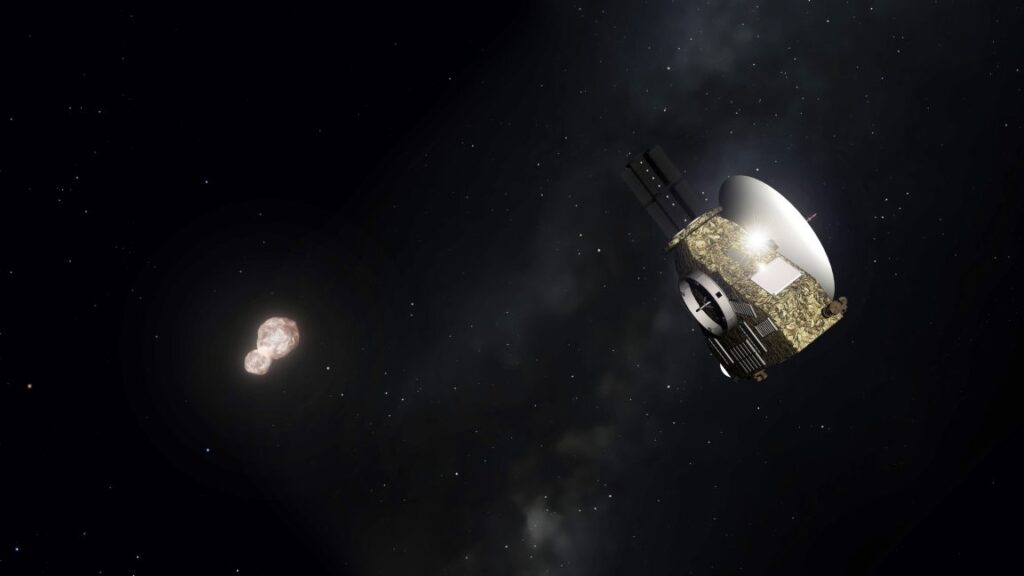

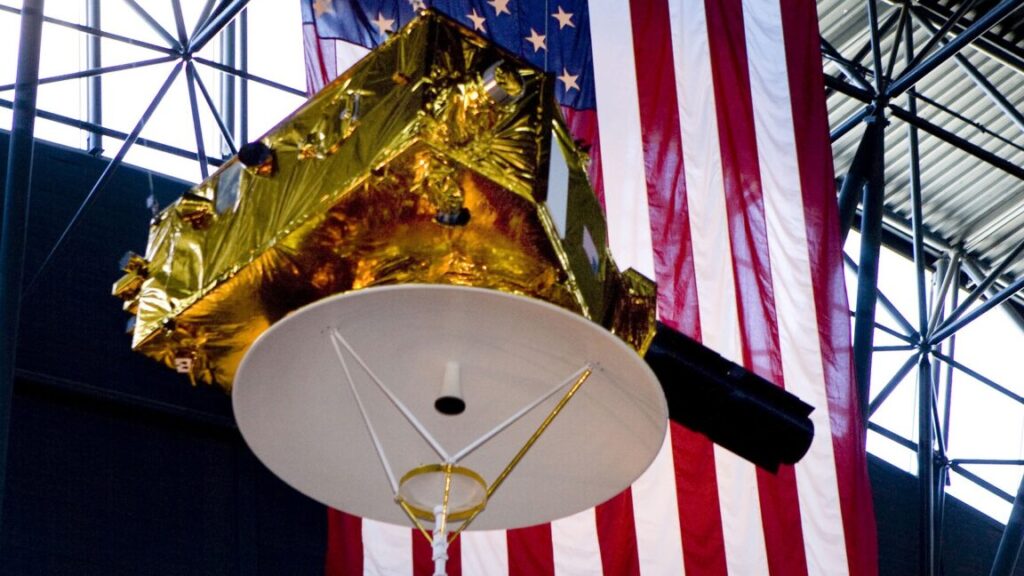

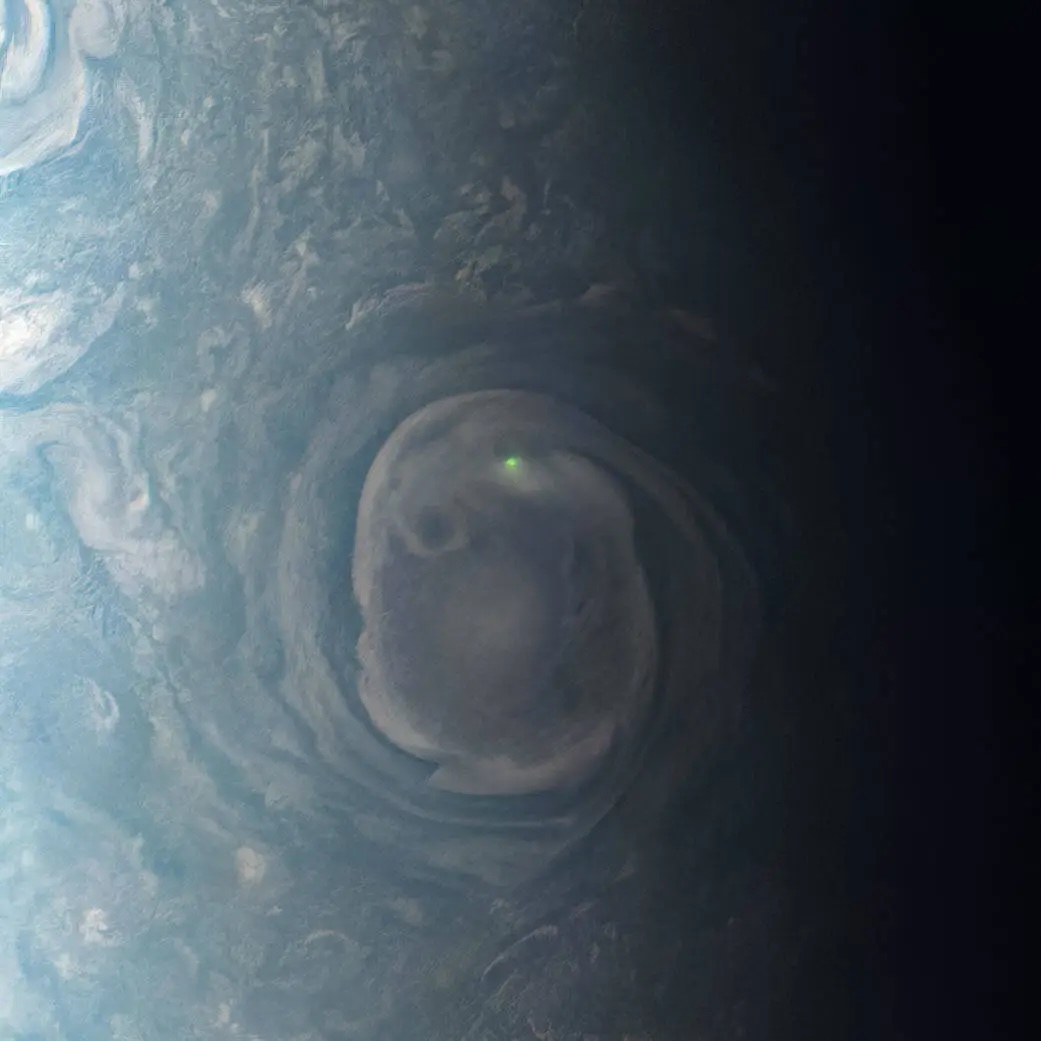

In the event of a shutdown, there has been much uncertainty about what would happen to NASA’s budget and the agency’s science missions. Earlier this summer, for example, the White House directed science mission leaders to prepare “closeout plans” for about two dozen spacecraft.

These science missions were targeted for cancellation under the president’s budget request for fiscal year 2026, and the development of these closeout plans indicated that, in the absence of a final budget from Congress, the White House could seek to end these (and other) programs beginning October 1.

However, two sources confirmed to Ars on Friday afternoon that interim NASA Administrator Sean Duffy has now directed the agency to work toward the budget level established in the House Appropriations Committee’s budget bill for the coming fiscal year. This does not support full funding for NASA’s science portfolio, but it is far more beneficial than the cuts sought by the White House.

In a win for science, NASA told to use House budget as shutdown looms Read More »