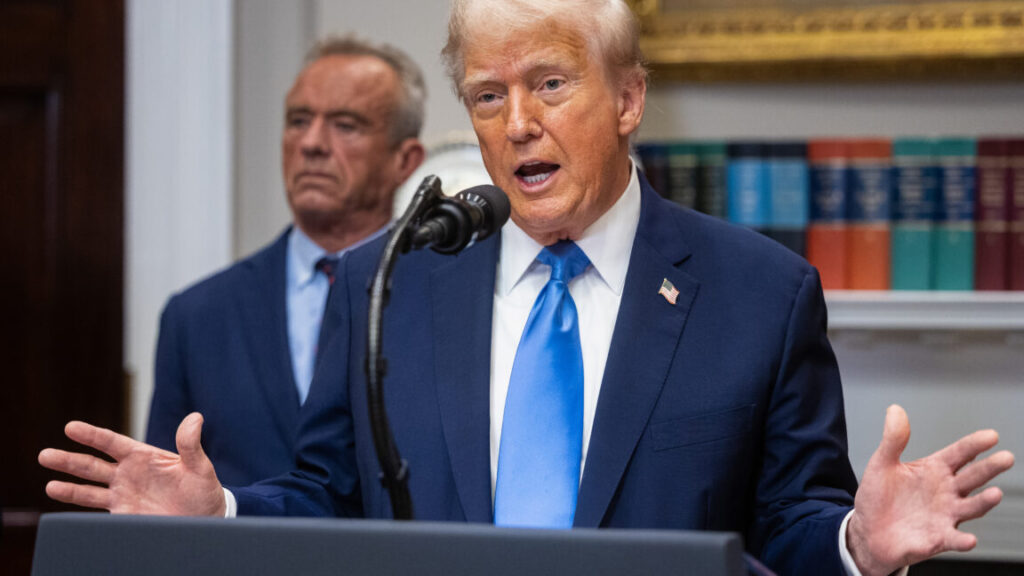

Controversial NIH director now in charge of CDC, too, in RFK Jr. shake-up

Insiders report that, as NIH director, Bhattacharya delegates most of his responsibilities for running the $47 billion agency to two top officials. Instead of a hands-on leader, Bhattacharya has become known for his many public interviews, earning him the nickname “Podcast Jay.”

“Malpractice”

Researchers expect that Bhattacharya will perform similarly at the helm of the CDC. Jenna Norton, an NIH program officer who spoke to the Guardian in her personal capacity, commented that Bhattacharya “won’t actually run the CDC. Just as he doesn’t actually run NIH.” His role for the administration, she added, “is largely as a propagandist.”

Jeremy Berg, former director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, echoed the sentiment to the Guardian. “Now, rather than largely ignoring the actual operations of one agency, he can largely ignore the actual operations of two,” he said.

Kayla Hancock, director of Public Health Watch, a nonprofit advocacy group, went further in a public statement, saying, “Jay Bhattacharya has overseen the most chaotic and rudderless era in NIH history, and for RFK Jr. to give him even more responsibility at the CDC is malpractice against the public health.”

Like other commenters, Hancock noted his apparent lack of involvement at the NIH and put it in the context of the current state of US public health. “This is the last person who should be overseeing the CDC at a time when preventable diseases like measles are roaring back under RFK Jr.’s deadly anti-vax agenda,” she said.

It is widely expected that Bhattacharya will, like O’Neill, act as a rubber-stamp for Kennedy’s relentless anti-vaccine agenda items. When Kennedy dramatically overhauled the CDC’s childhood vaccine schedule, slashing recommended vaccinations from 17 to 11 without scientific evidence, Bhattacharya was among the officials who signed off on the unprecedented change.

Ultimately, Bhattacharya will only be in the role for a short time, at least officially. The role of CDC director became a Senate-confirmed position in 2023, and, as such, an acting director can serve only 210 days from the date the role became vacant. That deadline comes up on March 25. President Trump has not nominated anyone to fill the director role.

Controversial NIH director now in charge of CDC, too, in RFK Jr. shake-up Read More »