ChatGPT users shocked to learn their chats were in Google search results

Faced with mounting backlash, OpenAI removed a controversial ChatGPT feature that caused some users to unintentionally allow their private—and highly personal—chats to appear in search results.

Fast Company exposed the privacy issue on Wednesday, reporting that thousands of ChatGPT conversations were found in Google search results and likely only represented a sample of chats “visible to millions.” While the indexing did not include identifying information about the ChatGPT users, some of their chats did share personal details—like highly specific descriptions of interpersonal relationships with friends and family members—perhaps making it possible to identify them, Fast Company found.

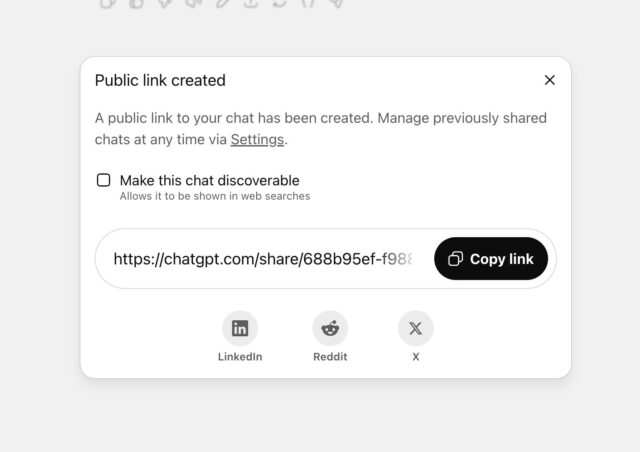

OpenAI’s chief information security officer, Dane Stuckey, explained on X that all users whose chats were exposed opted in to indexing their chats by clicking a box after choosing to share a chat.

Fast Company noted that users often share chats on WhatsApp or select the option to save a link to visit the chat later. But as Fast Company explained, users may have been misled into sharing chats due to how the text was formatted:

“When users clicked ‘Share,’ they were presented with an option to tick a box labeled ‘Make this chat discoverable.’ Beneath that, in smaller, lighter text, was a caveat explaining that the chat could then appear in search engine results.”

At first, OpenAI defended the labeling as “sufficiently clear,” Fast Company reported Thursday. But Stuckey confirmed that “ultimately,” the AI company decided that the feature “introduced too many opportunities for folks to accidentally share things they didn’t intend to.” According to Fast Company, that included chats about their drug use, sex lives, mental health, and traumatic experiences.

Carissa Veliz, an AI ethicist at the University of Oxford, told Fast Company she was “shocked” that Google was logging “these extremely sensitive conversations.”

OpenAI promises to remove Google search results

Stuckey called the feature a “short-lived experiment” that OpenAI launched “to help people discover useful conversations.” He confirmed that the decision to remove the feature also included an effort to “remove indexed content from the relevant search engine” through Friday morning.

ChatGPT users shocked to learn their chats were in Google search results Read More »