Sixteen Claude AI agents working together created a new C compiler

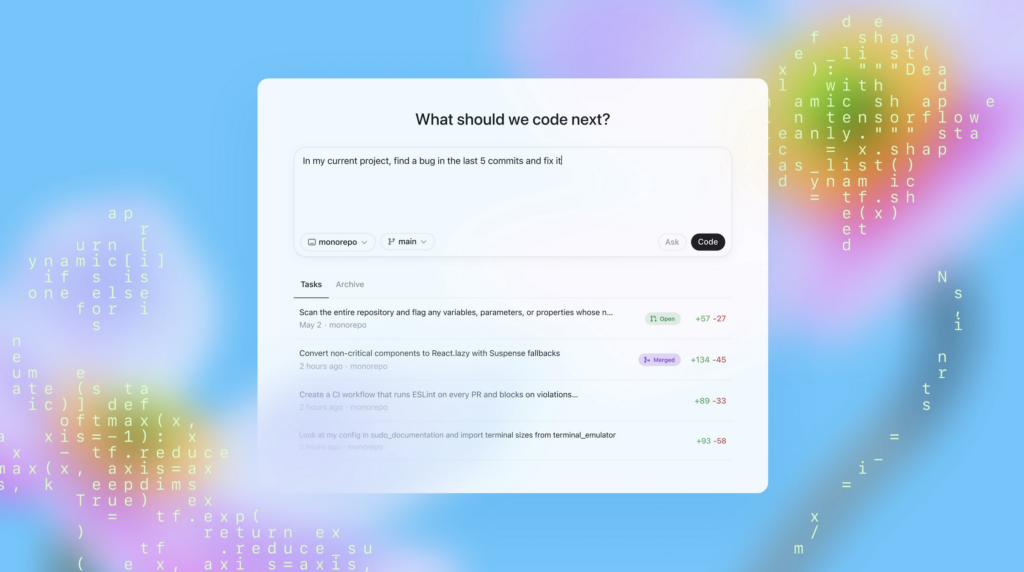

Amid a push toward AI agents, with both Anthropic and OpenAI shipping multi-agent tools this week, Anthropic is more than ready to show off some of its more daring AI coding experiments. But as usual with claims of AI-related achievement, you’ll find some key caveats ahead.

On Thursday, Anthropic researcher Nicholas Carlini published a blog post describing how he set 16 instances of the company’s Claude Opus 4.6 AI model loose on a shared codebase with minimal supervision, tasking them with building a C compiler from scratch.

Over two weeks and nearly 2,000 Claude Code sessions costing about $20,000 in API fees, the AI model agents reportedly produced a 100,000-line Rust-based compiler capable of building a bootable Linux 6.9 kernel on x86, ARM, and RISC-V architectures.

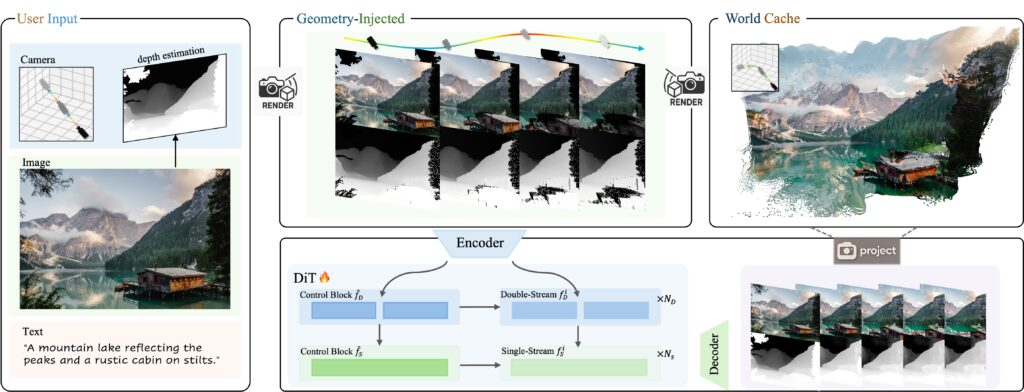

Carlini, a research scientist on Anthropic’s Safeguards team who previously spent seven years at Google Brain and DeepMind, used a new feature launched with Claude Opus 4.6 called “agent teams.” In practice, each Claude instance ran inside its own Docker container, cloning a shared Git repository, claiming tasks by writing lock files, then pushing completed code back upstream. No orchestration agent directed traffic. Each instance independently identified whatever problem seemed most obvious to work on next and started solving it. When merge conflicts arose, the AI model instances resolved them on their own.

The resulting compiler, which Anthropic has released on GitHub, can compile a range of major open source projects, including PostgreSQL, SQLite, Redis, FFmpeg, and QEMU. It achieved a 99 percent pass rate on the GCC torture test suite and, in what Carlini called “the developer’s ultimate litmus test,” compiled and ran Doom.

It’s worth noting that a C compiler is a near-ideal task for semi-autonomous AI model coding: The specification is decades old and well-defined, comprehensive test suites already exist, and there’s a known-good reference compiler to check against. Most real-world software projects have none of these advantages. The hard part of most development isn’t writing code that passes tests; it’s figuring out what the tests should be in the first place.

Sixteen Claude AI agents working together created a new C compiler Read More »