OpenAI sidesteps Nvidia with unusually fast coding model on plate-sized chips

But 1,000 tokens per second is actually modest by Cerebras standards. The company has measured 2,100 tokens per second on Llama 3.1 70B and reported 3,000 tokens per second on OpenAI’s own open-weight gpt-oss-120B model, suggesting that Codex-Spark’s comparatively lower speed reflects the overhead of a larger or more complex model.

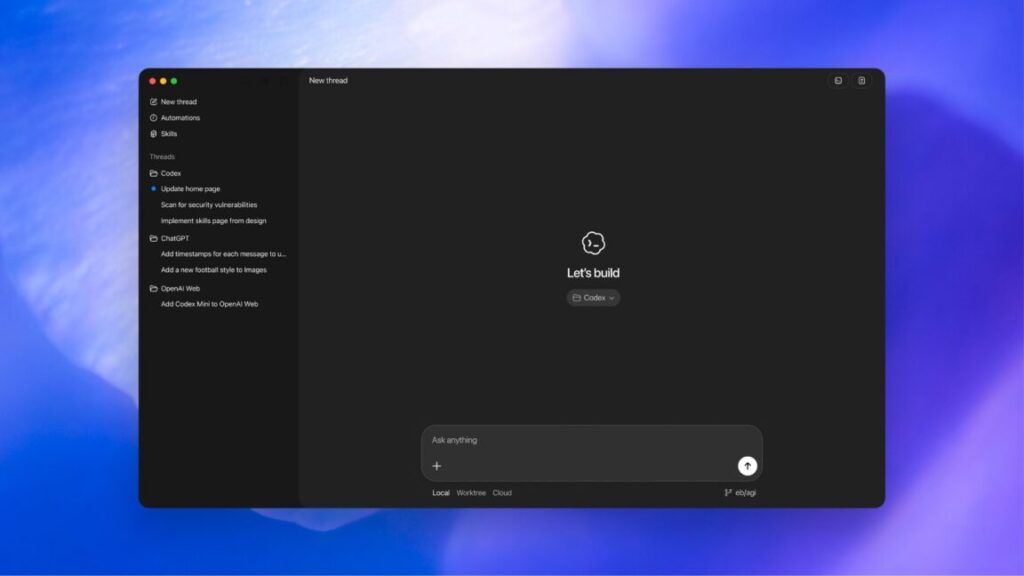

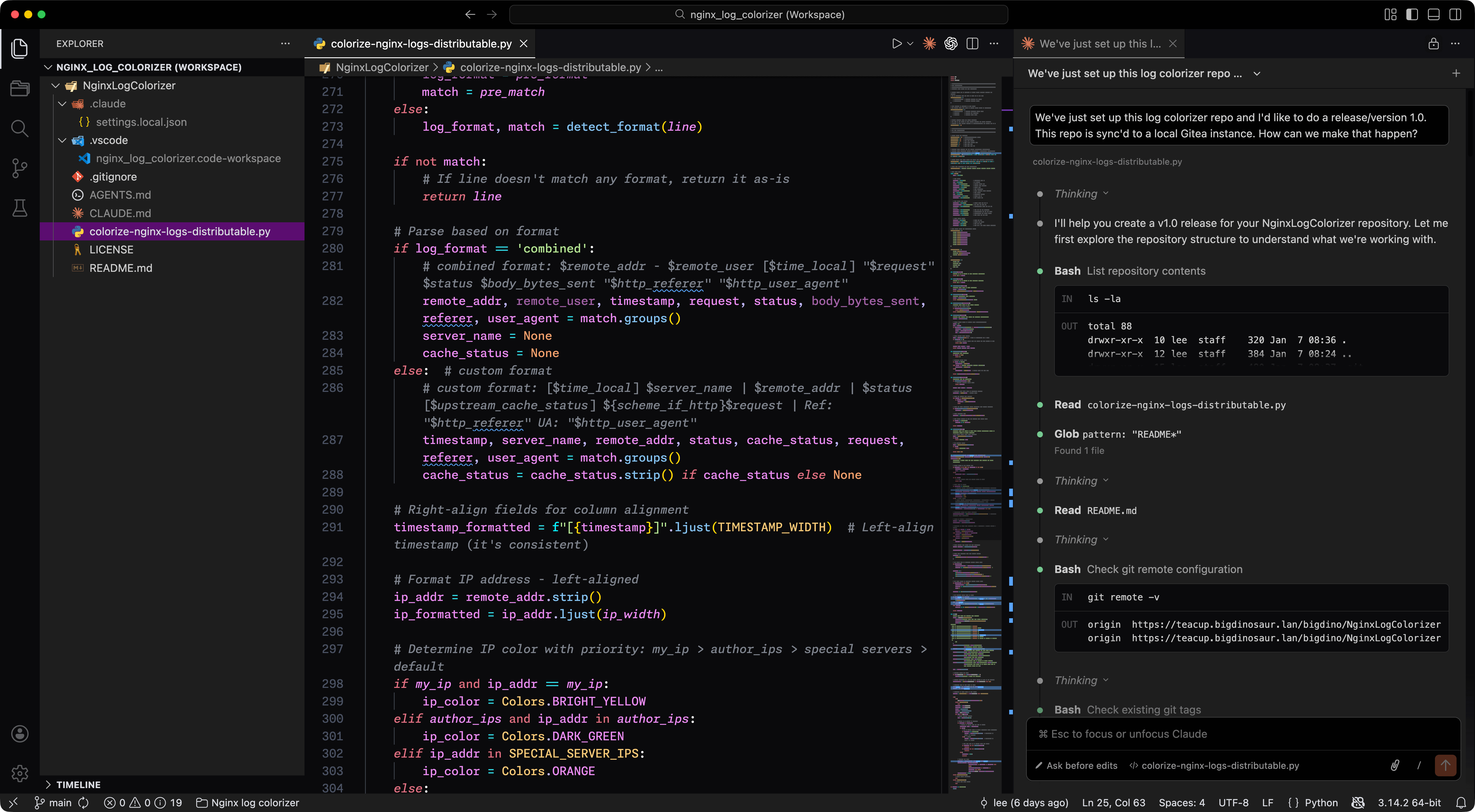

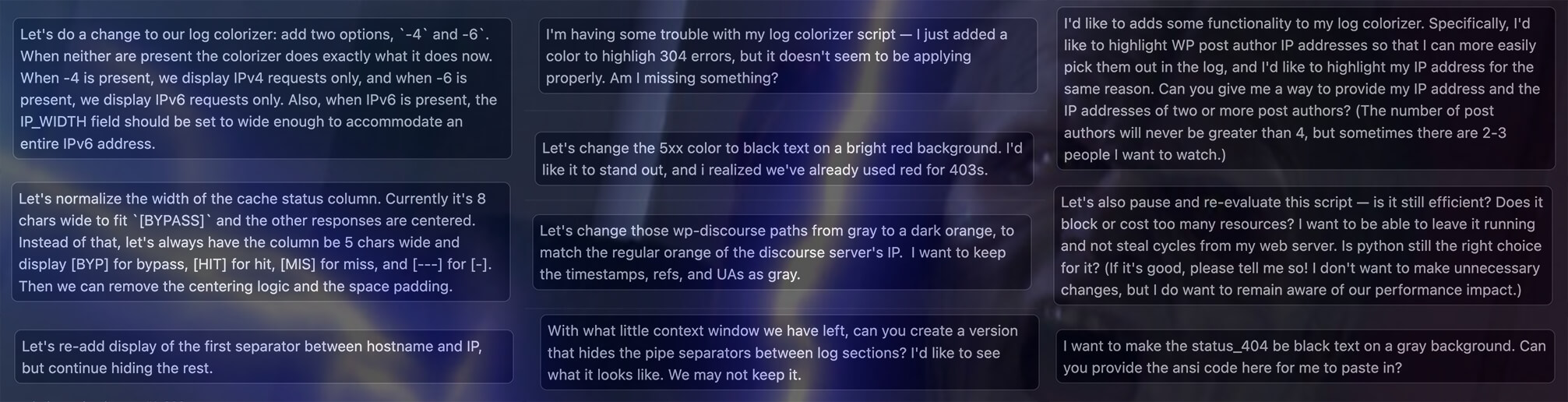

AI coding agents have had a breakout year, with tools like OpenAI’s Codex and Anthropic’s Claude Code reaching a new level of usefulness for rapidly building prototypes, interfaces, and boilerplate code. OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic have all been racing to ship more capable coding agents, and latency has become what separates the winners; a model that codes faster lets a developer iterate faster.

With fierce competition from Anthropic, OpenAI has been iterating on its Codex line at a rapid rate, releasing GPT-5.2 in December after CEO Sam Altman issued an internal “code red” memo about competitive pressure from Google, then shipping GPT-5.3-Codex just days ago.

Diversifying away from Nvidia

Spark’s deeper hardware story may be more consequential than its benchmark scores. The model runs on Cerebras’ Wafer Scale Engine 3, a chip the size of a dinner plate that Cerebras has built its business around since at least 2022. OpenAI and Cerebras announced their partnership in January, and Codex-Spark is the first product to come out of it.

OpenAI has spent the past year systematically reducing its dependence on Nvidia. The company signed a massive multi-year deal with AMD in October 2025, struck a $38 billion cloud computing agreement with Amazon in November, and has been designing its own custom AI chip for eventual fabrication by TSMC.

Meanwhile, a planned $100 billion infrastructure deal with Nvidia has fizzled so far, though Nvidia has since committed to a $20 billion investment. Reuters reported that OpenAI grew unsatisfied with the speed of some Nvidia chips for inference tasks, which is exactly the kind of workload that OpenAI designed Codex-Spark for.

Regardless of which chip is under the hood, speed matters, though it may come at the cost of accuracy. For developers who spend their days inside a code editor waiting for AI suggestions, 1,000 tokens per second may feel less like carefully piloting a jigsaw and more like running a rip saw. Just watch what you’re cutting.

OpenAI sidesteps Nvidia with unusually fast coding model on plate-sized chips Read More »