Astronomers are filling in the blanks of the Kuiper Belt

Are you out there, Planet X?

Next-generation telescopes are mapping this outer frontier.

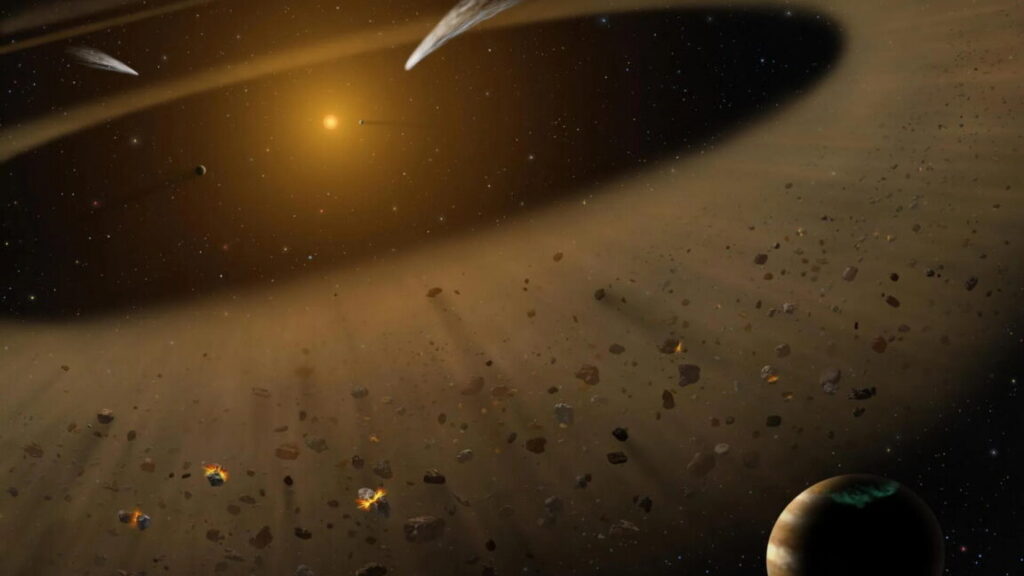

Credit: NASA/SOFIA/Lynette Cook

Out beyond the orbit of Neptune lies an expansive ring of ancient relics, dynamical enigmas, and possibly a hidden planet—or two.

The Kuiper Belt, a region of frozen debris about 30 to 50 times farther from the sun than the Earth is—and perhaps farther, though nobody knows—has been shrouded in mystery since it first came into view in the 1990s.

Over the past 30 years, astronomers have cataloged about 4,000 Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs), including a smattering of dwarf worlds, icy comets, and leftover planet parts. But that number is expected to increase tenfold in the coming years as observations from more advanced telescopes pour in. In particular, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will illuminate this murky region with its flagship project, the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), which began operating last year. Other next-generation observatories, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will also help to bring the belt into focus.

“Beyond Neptune, we have a census of what’s out there in the solar system, but it’s a patchwork of surveys, and it leaves a lot of room for things that might be there that have been missed,” says Renu Malhotra, who serves as Louise Foucar Marshall Science Research Professor and Regents Professor of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona.

“I think that’s the big thing that Rubin is going to do—fill out the gaps in our knowledge of the contents of the solar system,” she adds. “It’s going to greatly advance our census and our knowledge of the contents of the solar system.”

As a consequence, astronomers are preparing for a flood of discoveries from this new frontier, which could shed light on a host of outstanding questions. Are there new planets hidden in the belt, or lurking beyond it? How far does this region extend? And are there traces of cataclysmic past encounters between worlds—both homegrown or from interstellar space—imprinted in this largely pristine collection of objects from the deep past?

“I think this will become a very hot field very soon, because of LSST,” says Amir Siraj, a graduate student at Princeton University who studies the Kuiper Belt.

The Kuiper Belt is a graveyard of planetary odds and ends that were scattered far from the sun during the messy birth of the solar system some 4.6 billion years ago. Pluto was the first KBO ever spotted, more than a half-century before the belt itself was discovered.

Since the 1990s, astronomers have found a handful of other dwarf planets in the belt, such as Eris and Sedna, along with thousands of smaller objects. While the Kuiper Belt is not completely static, it is, for the most part, an intact time capsule of the early solar system that can be mined for clues about planet formation.

For example, the belt contains weird structures that may be signatures of past encounters between giant planets, including one particular cluster of objects, known as a “kernel,” located at about 44 astronomical units (AU), where one AU is the distance between Earth and the sun (about 93 million miles).

While the origin of this kernel is still unexplained, one popular hypothesis is that its constituent objects—which are known as cold classicals—were pulled along by Neptune’s outward migration through the solar system more than 4 billion years ago, which may have been a bumpy ride.

The idea is that “Neptune got jiggled by the rest of the gas giants and did a bit of a jump; it’s called the ‘jumping Neptune’ scenario,” says Wes Fraser, an astronomer at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, National Research Council of Canada, who studies the Kuiper Belt, noting that astronomer David Nesvorný came up with the idea.

“Imagine a snowplow driving along a highway, and lifting up the plow. It leaves a clump of snow behind,” he adds. “That same sort of idea is what left the clump of cold classicals behind. That is the kernel.”

In other words, Neptune tugged these objects along with it as it migrated outward, but then broke its gravitational hold over them when it “jumped,” leaving them to settle into the Kuiper Belt in the distinctive Neptune-sculpted kernel pattern that remains intact to this day.

Last year, Siraj and his advisers at Princeton set out to look for other hidden structures in the Kuiper Belt with a new algorithm that analyzed 1,650 KBOs—about 10 times as many objects as the 2011 study, led by Jean-Robert Petit, that first identified the kernel.

The results consistently confirmed the presence of the original kernel, while also revealing a possibly new “inner kernel” located at about 43 AU, though more research is needed to confirm this finding, according to the team’s 2025 study.

“You have these two clumps, basically, at 43 and 44 AU,” Siraj explains. “It’s unclear whether they’re part of the same structure,” but “either way, it’s another clue about, perhaps, Neptune’s migration, or some other process that formed these clumps.”

As Rubin and other telescopes discover thousands more KBOs in the coming years, the nature and possible origin of these mysterious structures in the belt may become clearer, potentially opening new windows into the tumultuous origins of our solar system.

In addition to reconstructing the early lives of the known planets, astronomers who study the Kuiper Belt are racing to spot unknown planets. The most famous example is the hypothetical giant world known as Planet Nine or Planet X, first proposed in 2016. Some scientists have suggested that the gravitational influence of this planet, if it exists, might explain strangely clustered orbits within the Kuiper Belt, though this speculative world would be located well beyond the belt, at several hundred AU.

Siraj and his colleagues have also speculated about the possibility of a Mercury- or Mars-sized world, dubbed Planet Y, that may be closer to the belt, at around 80 to 200 AU, according to their 2025 study. Rubin is capable of spotting these hypothetical worlds, though it may be challenging to anticipate the properties of planets that lurk this far from the sun.

“We know nothing about the atmospheres and surfaces of gas giant or ice giant type planets at 200, 300, or 400 AU,” Fraser says. “We know nothing about their chemistry. Every single time we look at an exoplanet, it behaves differently than what our models predict.”

“I think Planet Nine might very well just be a tar ball that is so dark that we can’t see it, and that’s why it hasn’t been discovered yet,” he adds. “If we found that, I wouldn’t be too surprised. And who knows what an Earth [in the belt] would look like? Certainly the compositional makeup will be different than a Mars, or an Earth, or a Venus, in the inner solar system.”

Observatories like Rubin and JWST may fill in these tantalizing gaps in our knowledge of the Kuiper Belt, and perhaps pinpoint hidden planets. But even if these telescopes reveal an absence of planets, it would be a breakthrough.

“There’s a lot of room for discovery of large bodies,” says Malhotra. “That would be awesome, but if we don’t find any, that would tell us something as well.”

“Not finding them up to some distance would give us estimates of how efficient or inefficient the planet formation process was,” she adds. “It would fill in some of the uncertainties that we have in our models.”

One other major open question about the Kuiper Belt is the extent of its boundaries. The belt suddenly tapers off at about 50 AU, an edge called the Kuiper cliff. This is a puzzling feature, because it suggests that our solar system has an anomalously small debris belt compared with other systems.

“The solar system looks kind of weird,” Fraser says. “The Kuiper cliff is a somewhat sharp delineation. Beyond that, we have no evidence that there was a disk of material. And yet, if you look at other stellar systems that have debris disks, the vast majority of those are significantly larger.”

“If we were to find a debris disk at, say, 100 AU, that would immediately make the solar system not weird, and quite average at that point,” he notes.

In 2024, Fraser and his colleagues presented hints of a possible undiscovered population of objects that may exist at about 100 AU—though he emphasizes that these are candidate detections, and are not yet confirmed to be a hidden outer ring.

However, even Rubin may not be able to resolve the presence of the tiny and distant objects that could represent a new outer limit of the Kuiper Belt. Time will tell.

As astronomers gear up for this major step change in our understanding of the Kuiper Belt, answers to some of our most fundamental questions hang in the balance. With its immaculate record of the early solar system, this region preserves secrets from the deep past. Here there are probably not dragons, but there may well be hidden planets, otherworldly structures, and discoveries that haven’t yet been imagined.

“I’d say the big question is, what’s out there?” Malhotra says. “What are we missing?”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

Astronomers are filling in the blanks of the Kuiper Belt Read More »