Quantum roundup: Lots of companies announcing new tech

More superposition, less supposition

IBM follows through on its June promises, plus more trapped ion news.

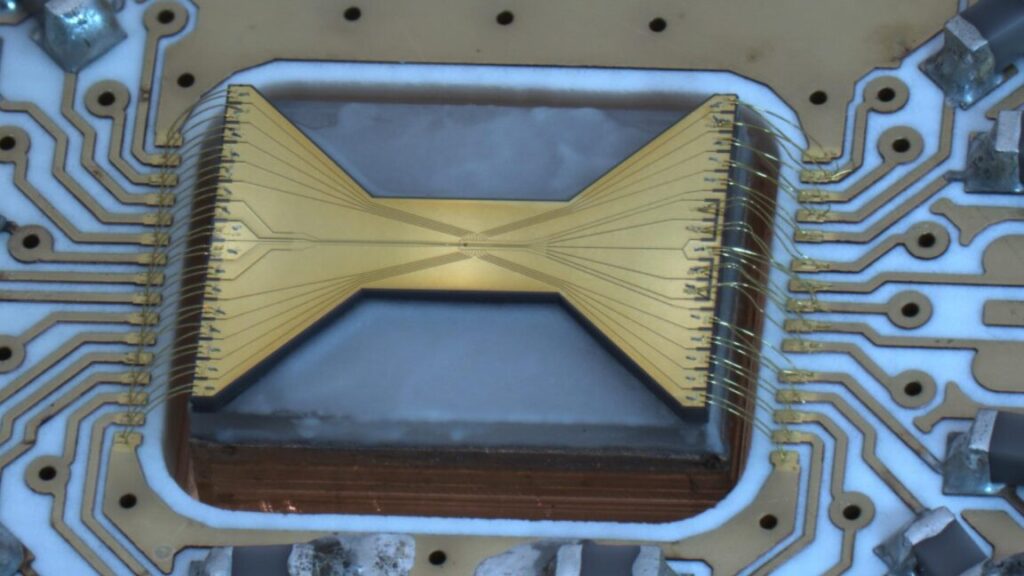

IBM has moved to large-scale manufacturing of its Quantum Loon chips. Credit: IBM

The end of the year is usually a busy time in the quantum computing arena, as companies often try to announce that they’ve reached major milestones before the year wraps up. This year has been no exception. And while not all of these announcements involve interesting new architectures like the one we looked at recently, they’re a good way to mark progress in the field, and they often involve the sort of smaller, incremental steps needed to push the field forward.

What follows is a quick look at a handful of announcements from the past few weeks that struck us as potentially interesting.

IBM follows through

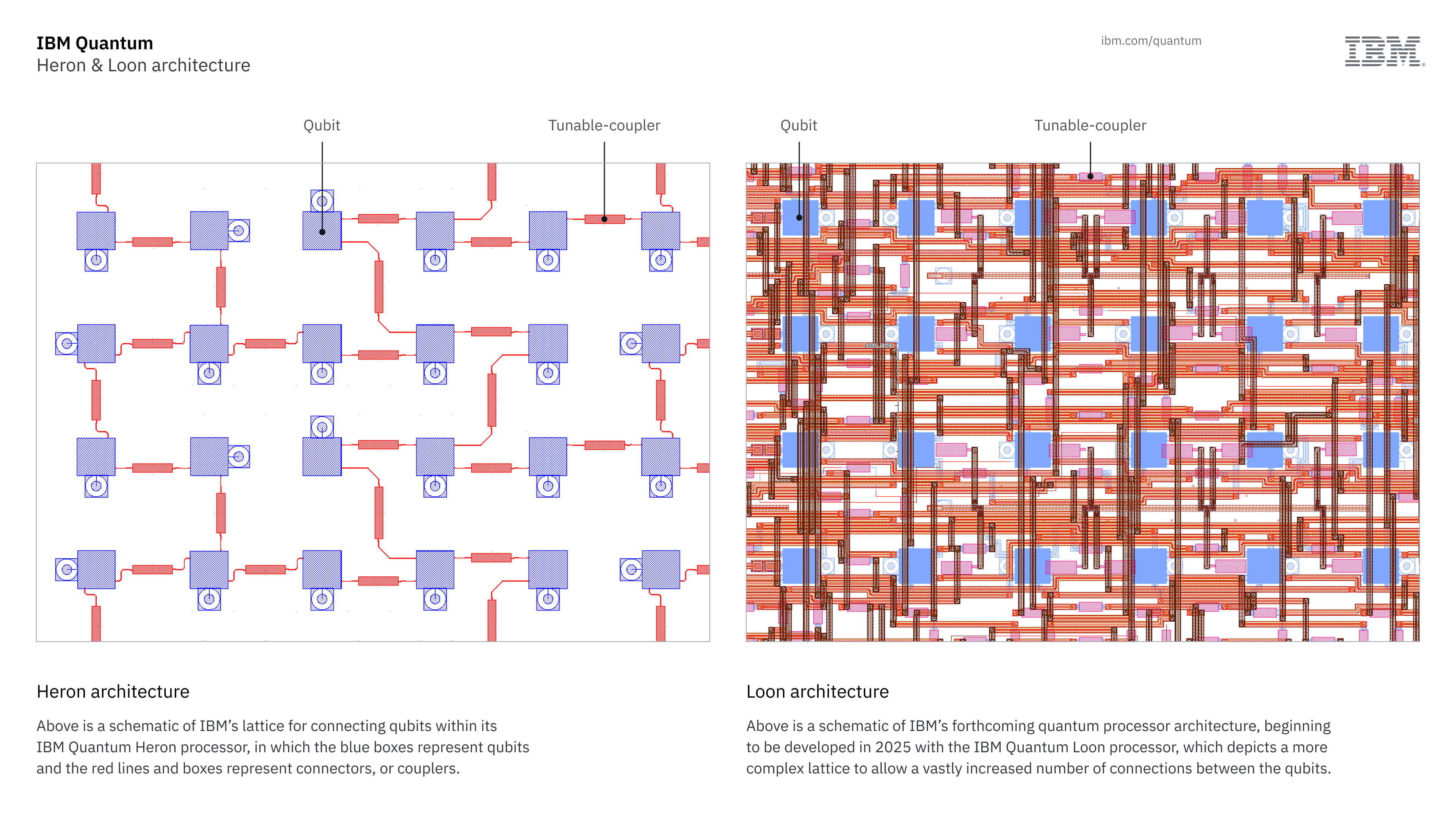

IBM is one of the companies announcing a brand new architecture this year. That’s not at all a surprise, given that the company promised to do so back in June; this week sees the company confirming that it has built the two processors it said it would earlier in the year. These include one called Loon, which is focused on the architecture that IBM will use to host error-corrected logical qubits. Loon represents two major changes for the company: a shift to nearest-neighbor connections and the addition of long-distance connections.

IBM had previously used what it termed the “heavy hex” architecture, in which alternating qubits were connected to either two or three of their neighbors, forming a set of overlapping hexagonal structures. In Loon, the company is using a square grid, with each qubit having connections to its four closest neighbors. This higher density of connections can enable more efficient use of the qubits during computations. But qubits in Loon have additional long-distance connections to other parts of the chip, which will be needed for the specific type of error correction that IBM has committed to. It’s there to allow users to test out a critical future feature.

The second processor, Nighthawk, is focused on the now. It also has the nearest-neighbor connections and a square grid structure, but it lacks the long-distance connections. Instead, the focus with Nighthawk is to get error rates down so that researchers can start testing algorithms for quantum advantage—computations where quantum computers have a clear edge over classical algorithms.

In addition, the company is launching a GitHub repository that will allow the community to deposit code and performance data for both classical and quantum algorithms, enabling rigorous evaluations of relative performance. Right now, those are broken down into three categories of algorithms that IBM expects are most likely to demonstrate a verifiable quantum advantage.

This isn’t the only follow-up to IBM’s June announcement, which also saw the company describe the algorithm it would use to identify errors in its logical qubits and the corrections needed to fix them. In late October, the company said it had confirmed that the algorithm could work in real time when run on an FPGA made in collaboration with AMD.

Record lows

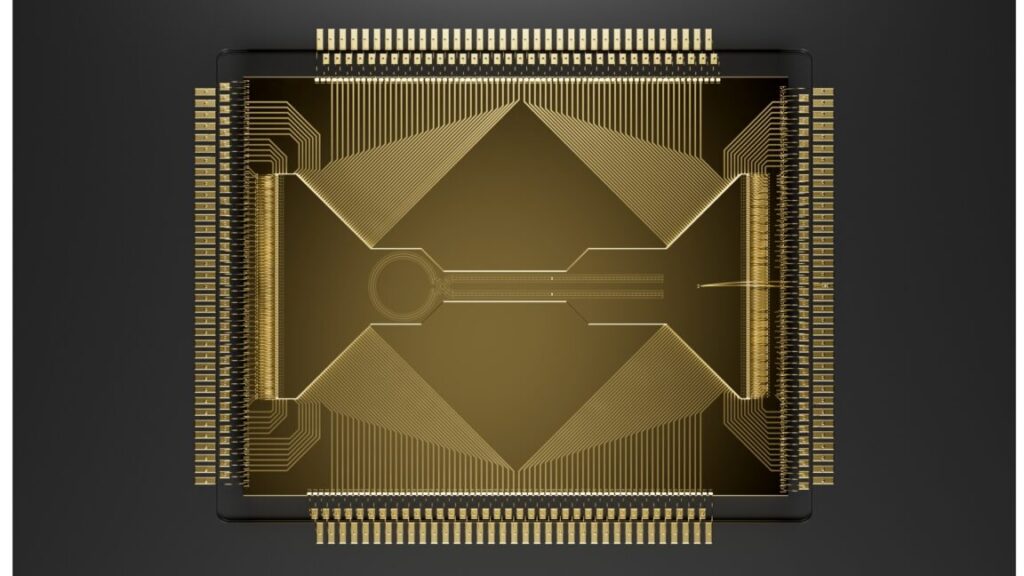

A few years back, we reported on a company called Oxford Ionics, which had just announced that it achieved a record low error rate in some qubit operations using trapped ions. Most trapped-ion quantum computers move qubits by manipulating electromagnetic fields, but they perform computational operations using lasers. Oxford Ionics figured out how to perform operations using electromagnetic fields, meaning more of their processing benefited from our ability to precisely manufacture circuitry (lasers were still needed for tasks like producing a readout of the qubits). And as we noted, it could perform these computational operations extremely effectively.

But Oxford Ionics never made a major announcement that would give us a good excuse to describe its technology in more detail. The company was ultimately acquired by IonQ, a competitor in the trapped-ion space.

Now, IonQ is building on what it gained from Oxford Ionics, announcing a new, record-low error rate for two-qubit gates: greater than 99.99 percent fidelity. That could be critical for the company, as a low error rate for hardware qubits means fewer are needed to get good performance from error-corrected qubits.

But the details of the two-qubit gates are perhaps more interesting than the error rate. Two-qubit gates involve bringing both qubits involved into close proximity, which often requires moving them. That motion pumps a bit of energy into the system, raising the ions’ temperature and leaving them slightly more prone to errors. As a result, any movement of the ions is generally followed by cooling, in which lasers are used to bleed energy back out of the qubits.

This process, which involves two distinct cooling steps, is slow. So slow that as much as two-thirds of the time spent in operations involves the hardware waiting around while recently moved ions are cooled back down. The new IonQ announcement includes a description of a method for performing two-qubit gates that doesn’t require the ions to be fully cooled. This allows one of the two cooling steps to be skipped entirely. In fact, coupled with earlier work involving one-qubit gates, it raises the possibility that the entire machine could operate with its ions at a still very cold but slightly elevated temperature, avoiding all need for one of the two cooling steps.

That would shorten operation times and let researchers do more before the limit of a quantum system’s coherence is reached.

State of the art?

The last announcement comes from another trapped-ion company, Quantum Art. A couple of weeks back, it announced a collaboration with Nvidia that resulted in a more efficient compiler for operations on its hardware. On its own, this isn’t especially interesting. But it’s emblematic of a trend that’s worth noting, and it gives us an excuse to look at Quantum Art’s technology, which takes a distinct approach to boosting the efficiency of trapped-ion computation.

First, the trend: Nvidia’s interest in quantum computing. The company isn’t interested in the quantum aspects (at least not publicly); instead, it sees an opportunity to get further entrenched in high-performance computing. There are three areas where the computational capacity of GPUs can play a role here. One is small-scale modeling of quantum processors so that users can perform an initial testing of algorithms without committing to paying for access to the real thing. Another is what Quantum Art is announcing: using GPUs as part of a compiler chain to do all the computations needed to find more efficient ways of executing an algorithm on specific quantum hardware.

Finally, there’s a potential role in error correction. Error correction involves some indirect measurements of a handful of hardware qubits to determine the most likely state that a larger collection (called a logical qubit) is in. This requires modeling a quantum system in real time, which is quite difficult—hence the computational demands that Nvidia hopes to meet. Regardless of the precise role, there has been a steady flow of announcements much like Quantum Art’s: a partnership with Nvidia that will keep the company’s hardware involved if the quantum technology takes off.

In Quantum Art’s case, that technology is a bit unusual. The trapped-ion companies we’ve covered so far are all taking different routes to the same place: moving one or two ions into a location where operations can be performed and then executing one- or two-qubit gates. Quantum Art’s approach is to perform gates with much larger collections of ions. At the compiler level, it would be akin to figuring out which qubits need a specific operation performed, clustering them together, and doing it all at once. Obviously, there are potential efficiency gains here.

The challenge would normally be moving so many qubits around to create these clusters. But Quantum Art uses lasers to “pin” ions in a row so they act to isolate the ones to their right from the ones to their left. Each cluster can then be operated on separately. In between operations, the pins can be moved to new locations, creating different clusters for the next set of operations. (Quantum Art is calling each cluster of ions a “core” and presenting this as multicore quantum computing.)

At the moment, Quantum Art is behind some of its competitors in terms of qubit count and performing interesting demonstrations, and it’s not pledging to scale quite as fast. But the company’s founders are convinced that the complexity of doing so many individual operations and moving so many ions around will catch up with those competitors, while the added efficiency of multiple qubit gates will allow it to scale better.

This is just a small sampling of all the announcements from this fall, but it should give you a sense of how rapidly the field is progressing—from technology demonstrations to identifying cases where quantum hardware has a real edge and exploring ways to sustain progress beyond those first successes.

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Quantum roundup: Lots of companies announcing new tech Read More »