Fiji’s ants might be the canary in the coal mine for the insect apocalypse

A new genetic technique lets museum samples track population dynamics.

In late 2017, a study by Krefeld Entomological Society looked at protected areas across Germany and discovered that two-thirds of the insect populations living in there had vanished over the last 25 years. The results spurred the media to declare we’re living through an “insect apocalypse,” but the reasons behind their absence were unclear. Now, a joint team of Japanese and Australian scientists have completed a new, multi-year study designed to get us some answers.

Insect microcosm

“In our work, we focused on ants because we have systematic ways for collecting them,” says Alexander Mikheyev, an evolutionary biologist at the Australian National University. “They are also a group with the right level of diversity, where you have enough species to do comparative studies.” Choosing the right location, he explained, was just as important. “We did it in Fiji, because Fiji had the right balance between isolation—which gave us a discrete group of animals to study—but at the same time was diverse enough to make comparisons,” Mikheyev adds.

Thus, the Fijian archipelago, with its 330 islands, became the model the team used to get some insights into insect population dynamics. A key difference from the earlier study was that Mikheyev and his colleagues could look at those populations across thousands of years, not just the last 25.

“Most of the previous studies looked at actual observational data—things we could come in and measure,” Mikheyev explains. The issue with those studies was that they could only account for the last hundred years or so, because that’s how long we have been systematically collecting insect samples. “We really wanted to understand what happened in the longer time frame,” Mikheyev says.

To do this, his team focused on community genomics—studying the collective genetic material of entire groups of organisms. The challenge is that this would normally require collecting thousands of ants belonging to hundreds of species across the entire Fijian archipelago. Given that only a little over 100 out of 330 islands in Fiji are permanently inhabited, this seemed like an insurmountable challenge.

To go around it, the team figured they could run its tests on ants already collected in Fijian museums. But that came with its own set of difficulties.

DNA pieces

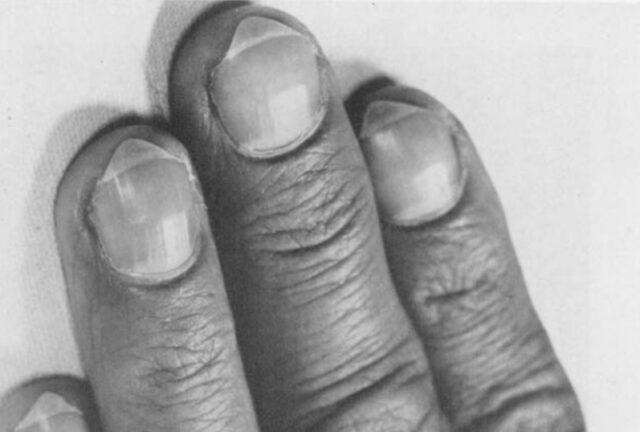

Unfortunately, the quality of DNA that could be obtained from museum collections was really bad. From the perspective of DNA preservation, the ants were obtained and stored in horrific conditions, since the idea was to showcase them for visitors, not run genetic studies. “People were catching them in malaise traps,” Mikheyev says. “A malaise trap is basically a bottle of alcohol that sits somewhere in Fiji for a month. Those samples had horribly fragmented, degraded DNA.”

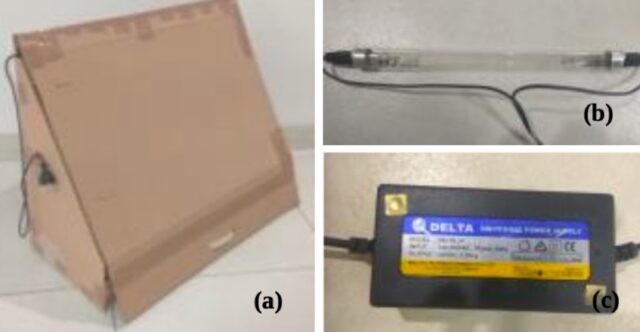

To work with this degraded genetic material, the team employed a technique they called high-throughput museumomics, a relatively new technique that looks at genetic differences across a genome without sequencing the whole thing. DNA sampled from multiple individuals was cut and marked with unique tags at the same repeated locations, a bit like using bookmarks to pinpoint the same page or passage in different issues of the same book. Then, the team sequenced short DNA fragments following the tag to look for differences between them, allowing them to evaluate the genetic diversity within a population. “We developed a series of methods that actually allowed us to harness these museum-grade specimens for population genetics,” Mikheyev explains.

But the trouble didn’t end there. Differences among Fijian ant taxa are based on their appearance, not genetic analysis. For years, researchers were collecting various ants and determining their species by looking at them. This led to 144 species belonging to 40 genera. For Mikheyev’s team, the first step was to look at the genomes in the samples and see if these species divisions were right. It turned out that they were mostly correct, but some species had to be split, while others were lumped together. At the end, the team confirmed that 127 species were represented among their samples.

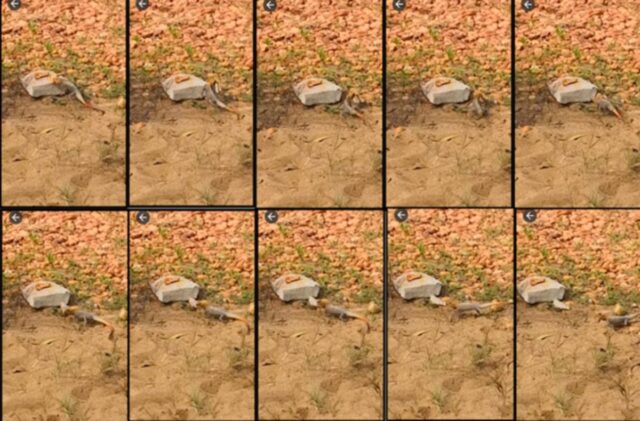

Overall, the team analyzed more than 4,000 specimens of ants collected over the past decade or so. And gradually, a turbulent history of Fijian ants started to emerge from the data.

The first colonists

The art of reconstructing the history of entire populations from individual genetic sequences relies on comparing them to each other thoroughly and running a whole lot of computer simulations. “We had multiple individuals per population,” Mikheyev explains. “Let’s say we look at this population and find it has essentially no diversity. It suggests that it very recently descended from a small number of individuals.” When the contrary was true and the diversity was high, the team assumed it indicated the population had been stable for a long time.

With the DNA data in hand, the team simulated how populations of ants would evolve over thousands of years under various conditions, and picked scenarios that best matched the genetic diversity results it obtained from real ants. “We identified multiple instances of colonization—broadscale evolutionary events that gave rise to the Fijian fauna that happened in different timeframes,” Mikheyev says. There was a total of at least 65 colonization events.

The first ants, according to Mikheyev, arrived at Fiji millions of years ago and gave rise to 88 endemic Fijian ant species we have today. These ants most likely evolved from a single ancestor and then diverged from their mainland relatives. Then, a further 23 colonization events introduced ants that were native to a broader Pacific region. These ants, the team found, were a mixture of species that colonized Fiji naturally and ones that were brought by the first human settlers, the Lapita people, who arrived around 3,000 years ago.

The arrival of humans also matched the first declines in endemic Fijian ant species.

Slash and burn

“In retrospect, these declines are not really surprising,” Mikheyev says. The first Fijian human colonists didn’t have the same population density as we have now, but they did practice things like slash-and-burn agriculture, where forests were cut down, left to dry, and burned to make space for farms and fertilize the soil. “And you know, not every ant likes to live in a field, especially the ones that evolved to live in a forest,” Mikheyev adds. But the declines in Fijian endemic ant species really accelerated after the first contact with the Europeans.

The first explorers in the 17th and 18th centuries, like Abel Tasman and James Cook, charted some of the Fijian islands but did not land there. The real apocalypse for Fijian ants began in the 19th century, when European sandalwood traders started visiting the archipelago on a regular basis and ultimately connected it to the global trade networks.

Besides the firearms they often traded for sandalwood with local chiefs, the traders also brought fire ants. “Fire ants are native to Latin America, and it’s a common invasive species extremely well adapted to habitats we create: lawns or clear-cut fields,” Mikheyev says. Over the past couple of centuries, his team saw a massive increase in fire ant populations, combined with accelerating declines in 79 percent of endemic Fijian ant species.

Signs of apocalypse

To Mikheyev, Fiji was just a proving ground to test the methods of working with museum-grade samples. “Now we know this approach works and we can start leveraging collections found in museums around the world—all of them can tell us stories about places where they were collected,” Mikheyev says. His ultimate goal is to look for the signs of the insect apocalypse, or any other apocalypse of a similar kind, worldwide.

But the question is whether what’s happening is really that bad? After all, not all ants seem to be in decline. Perhaps what we see is just a case of a better-adapted species taking over—natural selection happening before our eyes?

“Sure, we can just live with fire ants all along without worrying about the kind of beautiful biodiversity that evolution has created on Fiji,” Mikheyev says. “But I feel like if we just go with that philosophy, we’re really going to be irreparably losing important and interesting parts of our ecology.” If the current trends persist, he argues, we might lose endemic Fijian ants forever. “And this would make our world worse, in many ways,” Mikheyev says.

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.ads3004

Fiji’s ants might be the canary in the coal mine for the insect apocalypse Read More »