Managers on alert for “launch fever” as pressure builds for NASA’s Moon mission

“Putting crew on the rocket and taking the crew around the Moon, this is going be our first step toward a sustained lunar presence,” Honeycutt said. “It’s 10 days [and] four astronauts going farther from Earth than any other human has ever traveled. We’ll be validating the Orion spacecraft’s life support, navigation and crew systems in the really harsh environments of deep space, and that’s going to pave the way for future landings.”

NASA’s 322-foot-tall (98-meter) SLS rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building on the eve of rollout to Launch Complex 39B. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

There is still much work ahead before NASA can clear Artemis II for launch. At the launch pad, technicians will complete final checkouts and closeouts before NASA’s launch team gathers in early February for a critical practice countdown. During this countdown, called a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR), Blackwell-Thompson and her team will oversee the loading of the SLS rocket’s core stage and upper stage with super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

The cryogenic fluids, particularly liquid hydrogen, gave fits to the Artemis launch team as NASA prepared to launch the Artemis I mission—without astronauts—on the SLS rocket’s first test flight in 2022. Engineers resolved the issues and successfully launched the Artemis I mission in November 2022, and officials will apply the lessons for the Artemis II countdown.

“Artemis I was a test flight, and we learned a lot during that campaign getting to launch,” Blackwell-Thompson said. “And the things that we’ve learned relative to how to go load this vehicle, how to load LOX (liquid oxygen), how to load hydrogen, have all been rolled in to the way in which we intend to do for the Artemis II vehicle.”

Finding the right time to fly

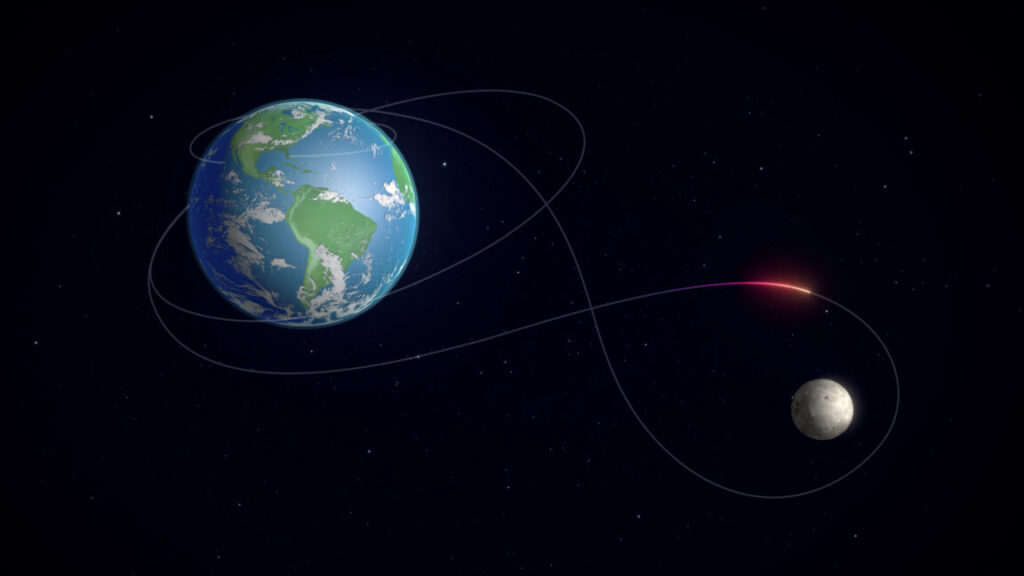

Assuming the countdown rehearsal goes according to plan, NASA could be in a position to launch the Artemis II mission as soon as February 6. But the schedule for February 6 is tight, with no margin for error. Officials typically have about five days per month when they can launch Artemis II, when the Moon is in the right position relative to Earth, and the Orion spacecraft can follow the proper trajectory toward reentry and splashdown to limit stress on the capsule’s heat shield.

In February, the available launch dates are February 6, 7, 8, 10, and 11, with launch windows in the overnight hours in Florida. If the mission isn’t off the ground by February 11, NASA will have to stand down until a new series of launch opportunities beginning March 6. The space agency has posted a document showing all available launch dates and times through the end of April.

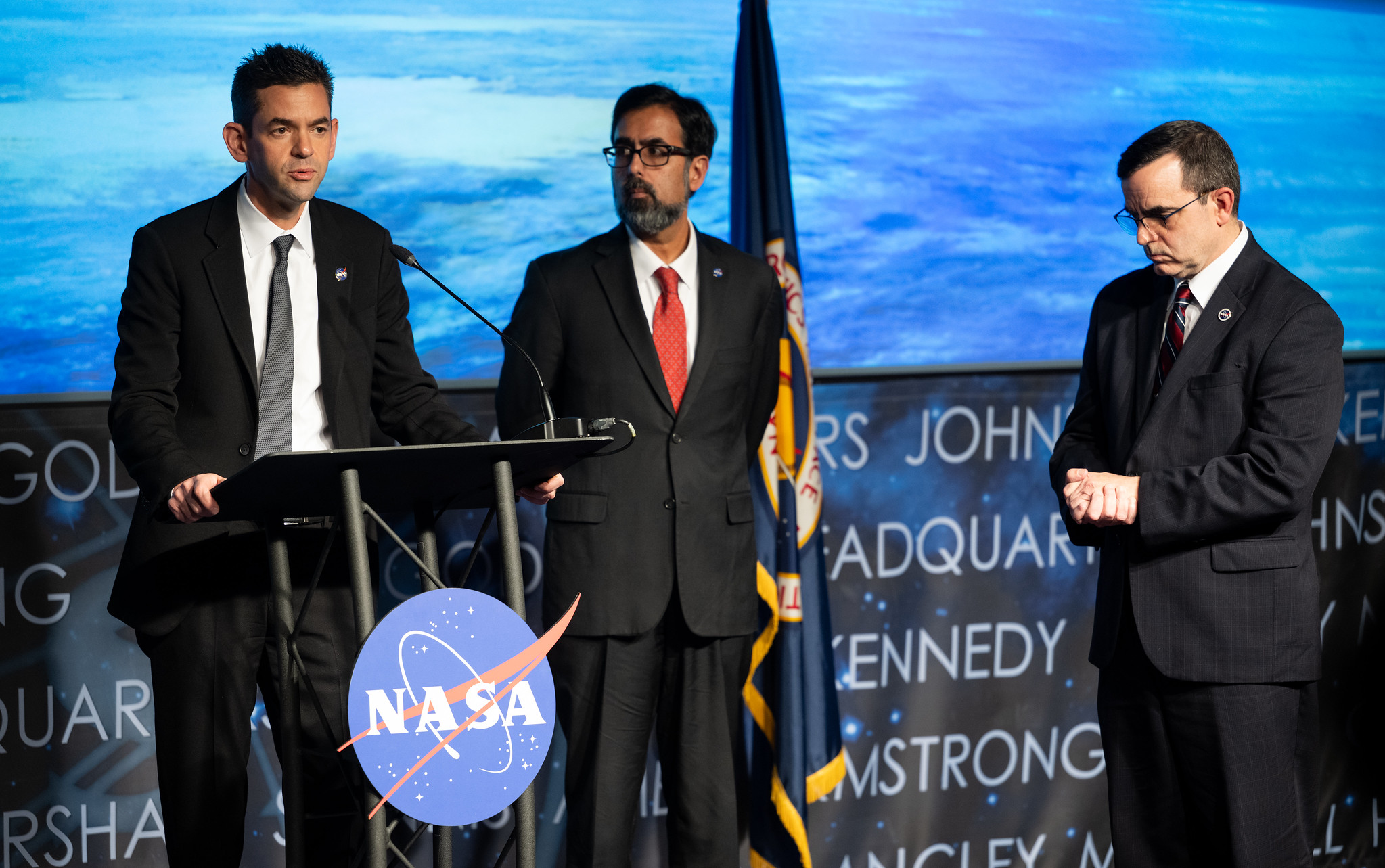

John Honeycutt, chair NASA’s Mission Management Team for the Artemis II mission, speaks during a news conference at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 16, 2026. Credit: Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

NASA’s leaders are eager for Artemis II to fly. NASA is not only racing China, a reality the agency’s former administrator acknowledged during the Biden administration. Now, the Trump administration is pushing NASA to accomplish a human landing on the Moon by the end of his presidential term on January 20, 2029.

One of Honeycutt’s jobs as chair of the Mission Management Team (MMT) is ensuring all the Is are dotted and Ts are crossed amid the frenzy of final launch preparations. While the hardware for Artemis II is on the move in Florida, the astronauts and flight controllers are wrapping up their final training and simulations at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“I think I’ve got a good eye for launch fever,” he said Friday.

“As chair of the MMT, I’ve got one job, and it’s the safe return of Reid, Victor, Christina, and Jeremy. I consider that a duty and a trust, and it’s one I intend to see through.”

Managers on alert for “launch fever” as pressure builds for NASA’s Moon mission Read More »