Simulations find ghostly whirls of dark matter trailing galaxy arms

“Basically what you do is you set up a bunch of particles that represent things like stars, gas, and dark matter, and you let them evolve for millions of years,” Bernet says. “Human lives are much too short to witness this happening in real time. We need simulations to help us see more than the present, which is like a single snapshot of the Universe.”

Several other groups already had galaxy simulations they were using to do other science, so the team asked one to see their data. When they found the dark matter imprint they were looking for, they checked for it in another group’s simulation. They found it again, and then in a third simulation as well.

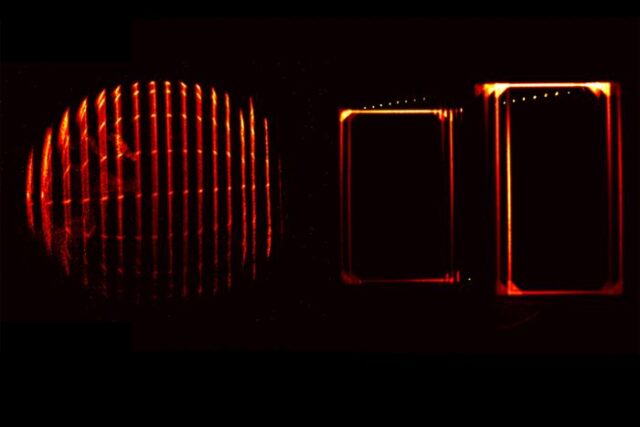

The dark matter spirals are much less pronounced than their stellar counterparts, but the team noted a distinct imprint on the motions of dark matter particles in the simulations. The dark spiral arms lag behind the stellar arms, forming a sort of unseen shadow.

These findings add a new layer of complexity to our understanding of how galaxies evolve, suggesting that dark matter is more than a passive, invisible scaffolding holding galaxies together. Instead, it appears to react to the gravity from stars in galaxies’ spiral arms in a way that may even influence star formation or galactic rotation over cosmic timescales. It could also explain the relatively newfound excess mass along a nearby spiral arm in the Milky Way.

The fact that they saw the same effect in differently structured simulations suggests that these dark matter spirals may be common in galaxies like the Milky Way. But tracking them down in the real Universe may be tricky.

Bernet says scientists could measure dark matter in the Milky Way’s disk. “We can currently measure the density of dark matter close to us with a huge precision,” he says. “If we can extend these measurements to the entire disk with enough precision, spiral patterns should emerge if they exist.”

“I think these results are very important because it changes our expectations for where to search for dark matter signals in galaxies,” Brooks says. “I could imagine that this result might influence our expectation for how dense dark matter is near the solar neighborhood and could influence expectations for lab experiments that are trying to directly detect dark matter.” That’s a goal scientists have been chasing for nearly 100 years.

Ashley writes about space for a contractor for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center by day and freelances in her free time. She holds master’s degrees in space studies from the University of North Dakota and science writing from Johns Hopkins University. She writes most of her articles with a baby on her lap.

Simulations find ghostly whirls of dark matter trailing galaxy arms Read More »