As always, some people need practical advice, and we can’t agree on how any of this works and we are all different and our motivations are different, so figuring out the best things to do is difficult. Here are various hopefully useful notes.

-

Effectiveness of GLP-1 Drugs.

-

What Passes for Skepticism on GLP-1s.

-

The Joy of Willpower.

-

Talking Supply.

-

Talking Price.

-

GLP-1 Inhibitors Help Solve All Your Problems.

-

Dieting the Hard Way.

-

Nutrients.

-

Are Vegetables a Scam?.

-

Government Food Labels Are Often Obvious Nonsense.

-

Sleep.

-

Find a Way to Enjoy Exercise.

-

A Note on Alcohol.

-

Focus Only On What Matters.

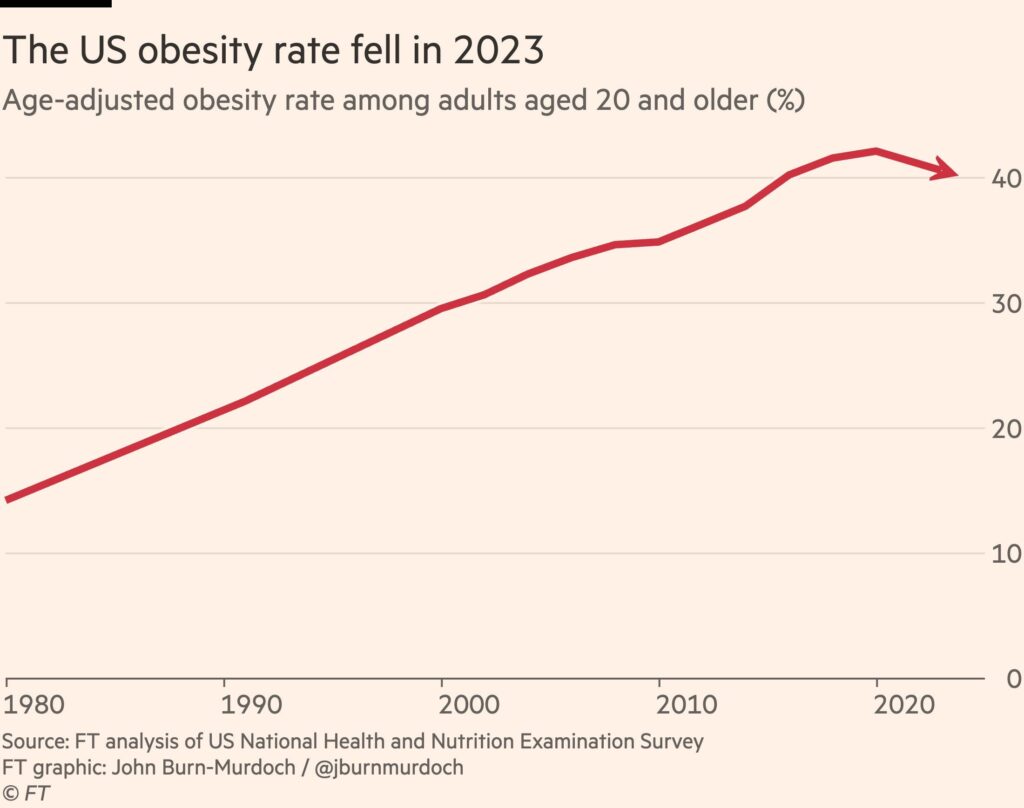

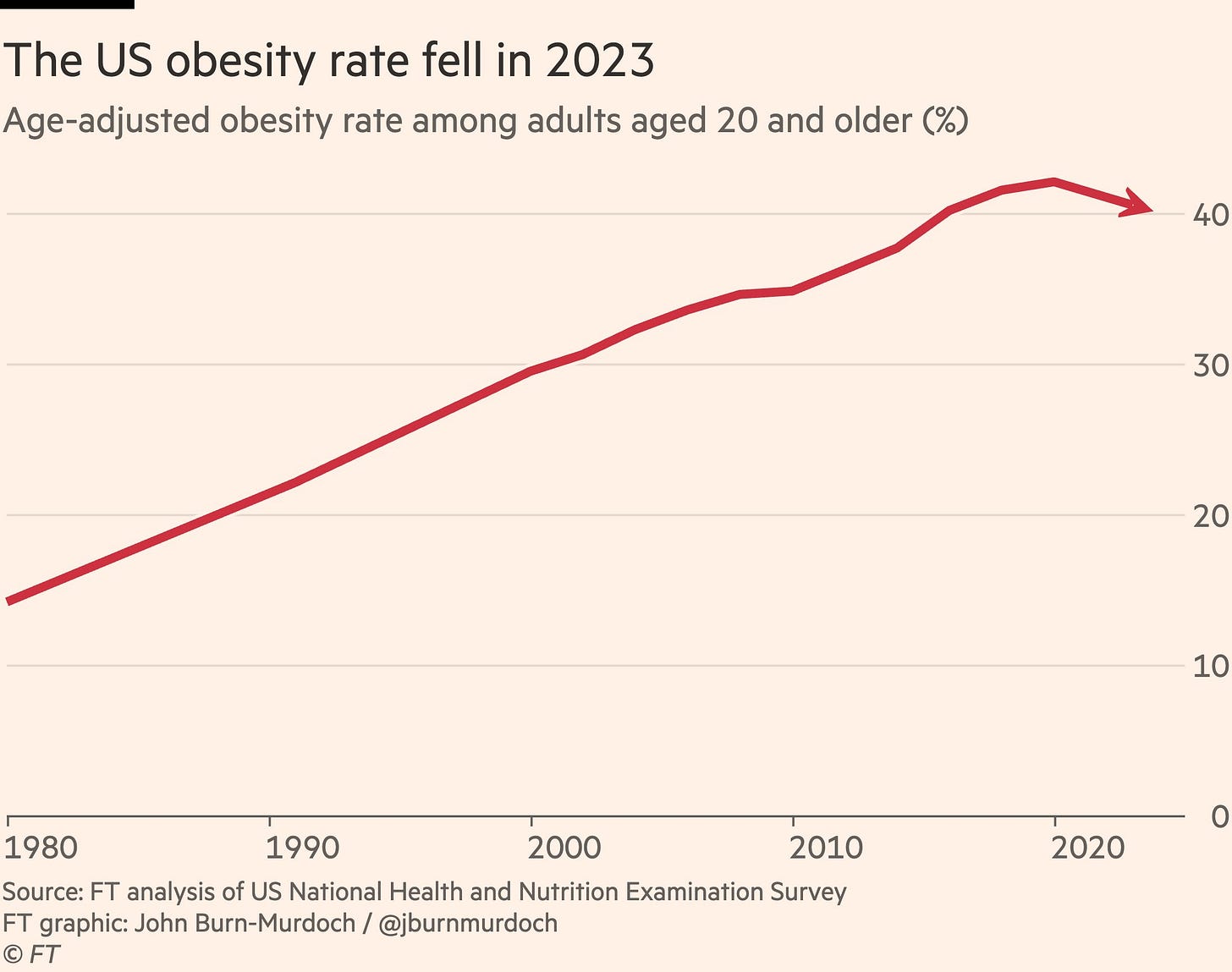

GLP-1 drugs are so effective that the American obesity rate is falling.

John Burn-Murdoch: While we can’t be certain that the new generation of drugs are behind this reversal, it is highly likely. For one, the decline in obesity is steepest among college graduates, the group using them at the highest rate.

In the college educated group the decline is about 20% already. This is huge.

This and our other observations are not easy to reconcile with this study, which I note for completeness and shows only 5% average weight loss in obese patients after one year. Which would be a spectacular result for any other drug. There’s a lot of data that says that in real world conditions you do a hell of a lot better on average than 5% here.

Here’s a strange framing from the AP: ‘As many as 1 in 5 people won’t lose weight with GLP-1 drugs, experts say.’

Jonel Aleccia: “I have been on Wegovy for a year and a half and have only lost 13 pounds,” said Griffin, who watches her diet, drinks plenty of water and exercises regularly. “I’ve done everything right with no success. It’s discouraging.”

Whether or not that is 13 more pounds than he would have lost otherwise, it’s not the worst outcome, as opposed to the 5 in 5 people who won’t lose weight without GLP-1 drugs. 4 out of 5 is pretty damn exciting. I love those odds.

Eliezer Yudkowsky offers caveats on GLP-1 drugs regarding muscle mass. Even if these concerns turn out to be fully correct, the drugs still seems obviously worthwhile to me for those who need it and where it solves their problems.

He also reports it did not work for him, causing the usual replies full of 101-level suggestions he’s already tried.

I presume it would not work for me, either. Its mechanism does not solve my problems. I actually can control my diet and exercise choices, within certain limits, if only through force of will.

My issue is a stupidly slow metabolism. Enjoying and craving food less wouldn’t help.

That’s the real best argument I know against GLP-1s, that it only works on the motivation and willpower layer, so if you’ve got that layer handled and your problems lie elsewhere, it won’t help you.

And also cultivating the willpower layer can be good.

Samo Burja: Compelling argument. Papers by lying academics or tweets by grifters pale in comparison.

This is the state of the art in nutrition science and is yet to be surpassed.

I’m embarking on this diet experiment, starting today. 💪

People ask me if I’m on Ozempic, and I say no.

Don’t you understand the joy of willpower?

How much should we care about whether we are using willpower?

There are three reasons we could care about this.

-

Use of willpower cultivates willpower or is otherwise ‘good for you.’

-

Use of willpower signals willpower.

-

The positional advantage of willpower is shrinking and we might not like that.

Wayne Burkett: People do this thing where they pretend not to understand why anybody would care that drugs like Ozempic eliminate the need to apply willpower to lose weight, but I think basically everybody understands on some level that the application of willpower is good for the souls of the people who are capable of it.

This is concern one.

There are two conflicting models you see on this.

-

The more you use willpower, the more you build up your willpower.

-

The more you use willpower, the more you run out of willpower.

This is where it gets complicated.

-

There’s almost certainly a short-term cost to using willpower. On days you have to use willpower on eating less, you are going to have less of it, and less overall capacity, for other things. So that’s a point in favor of GLP-1s.

-

That short-term cost doesn’t ever fully go away. If you’re on a permanent diet, yes it likely eventually gets easier via habits, but it’s a cost you pay every day. I pay it every day, and this definitely uses a substantial portion of my total willpower, despite having pulled this off for over 20 years.

-

The long-term effect of using willpower and cultivating related habits seems to have a positive effect on some combination of overall willpower and transfer into adjacent domains, and one’s self-image, and so on. You learn a bunch of good meta habits.

-

If you don’t have to spend the willpower on food, you could instead build up those same meta habits elsewhere, such as on exercise or screen time.

-

However, eating is often much better at providing motivation for learning to use willpower than alternative options. People might be strictly better off in theory, and still be worse off in practice.

My guess is that for most people, especially most people who have already tried hard to control their weight, this is a net positive effect.

I agree that there are some, especially in younger generations who don’t have the past experience of trying to diet via willpower, and who might decide they don’t need willpower, who might end up a lot worse off.

It’s a risk. But in general we should have a very high bar before we act as if introducing obstacles to people’s lives is net positive for them, or in this case that dieting is net worthwhile ‘willpower homework.’ Especially given that quite a lot of people seem to respond to willpower being necessary to not fail at this, by failing.

Then we get to a mix of the second and third objections.

Wayne Burkett: If you take away that need, then you level everybody else up, but you also level down the people who are well adapted to that need.

That’s probably a net win — not even probably, almost certainly — but it’s silly to pretend not to understand that there’s an element to all these things that’s positional.

An element? Sure. If you look and feel better than those around you, and are healthier than they are, then you have a positional advantage, and are more likely to win competitions than if everyone was equal, and you signal your willpower and all that.

I would argue it is on net rather small portion of the advantages.

My claim is that most of being a healthy weight is an absolute good, not a positional good. The health benefits are yours. The physically feeling better and actually looking better and being able to do more things and have more energy benefits are absolute.

Also, it’s kind of awesome when those around you are all physically healthy and generally more attractive? There are tons of benefits, to you, from that. Yes, relative status will suffer, and that is a real downside for you in competitions, especially winner-take-all competitions (e.g. the Hollywood problem) and when this is otherwise a major factor in hiring.

But you suffer a lot less in dating and other matching markets, and again I think the non-positional goods mostly dominate. If I could turn up or down the health and attractiveness of everyone around me, but I stayed the same, purely for my selfish purposes, I would very much help everyone else out.

I actually say this as someone who does have a substantial amount of my self-image wrapped up in having succeeded in being thin through the use of extreme amounts of willpower, although of course I have other fallbacks available.

A lot of people saying this sort of stuff pretty obviously just don’t have a lot of their personality wrapped up in being thin or in shape and would see this a lot more clearly if a drug were invented that equalized everyone’s IQ. Suddenly they’d be a little nervous about giving everybody equal access to the thing they think makes them special.

“But it’s really bad that these things are positional and we should definitely want to level everybody up” says the guy who is currently positioned at the bottom.

This is a theoretical, but IQ is mostly absolute. And there is a reason it is good advice to never be the smartest person in the room. It would be obviously great to raise everyone up if it didn’t also involve knocking people down.

Would it cost some amount of relative status? Perhaps, but beyond worth it.

In the end, I’m deeply unsympathetic to the second and third concerns above – your willpower advantage will still serve you well, you are not worse off overall, and so on.

In terms of cultivating willpower over the long term, I do have long term concerns we could be importantly limiting opportunities for this, in particular because it provides excellent forms of physical feedback. But mostly I think This Is Fine. We have lots of other opportunities to cultivate willpower. What convinces me is that we’ve already reached a point where it seems most people don’t use food to cultivate willpower. At some point, you are Socrates complaining about the younger generation reading, and you have to get over it.

We can’t get enough supply of those GLP-1s, even at current prices. The FDA briefly said we no longer had a shortage and people would have to stop making unauthorized versions via compounding, but intense public pressure they reversed their position two weeks later.

Should Medicare and Medicaid cover GLP-1? Republicans are split. My answer is that if we have sufficient supply available, then obviouslyh yes, even at current prices, although we probably can’t stomach it. While we are supply limited, obviously no.

Tyler Cowen defends the prices Americans pay for GLP-1 drugs, saying they support future R&D and that you can get versions for as low as $400/month or do even better via compounding.

I buy that the world needs to back up the truck and pay Novo Nordisk the big bucks. They’ve earned it and the incentives are super important to ensure we continue doing research going forward, and we need to honor our commitments. But this does not address several key issues.

The first key issue is that America is paying disproportionately, while others don’t pay their fair share. Together we should pay, and yes America benefits enough that the ‘rational’ thing to do is pick up the check even if others won’t, including others who could afford to.

But that’s also a way to ensure no one else ever pays their share, and that kind of ‘rational’ thinking is not ultimately rational, which is something both strong rationalists and Donald Trump have figured out in different ways. At some point it is a sucker’s game, and we should pay partly on condition that others also pay. Are we at that point with prescription drugs, or GLP-1 inhibitors in particular?

One can also ask whether Tyler’s argument proves too much – is it arguing we should choose to pay double the going market prices? Actively prevent discounting? If we don’t, does that make us ‘the supervillains’? Is this similar to Peter Singer’s argument about the drowning child?

The second key issue is that the incentives this creates are good on the research side, but bad on the consumption side. Monopoly pricing creates large deadweight losses.

The marginal cost of production is low, but the marginal cost of consumption is high, meaning a rather epic deadweight loss triangle from consumers who would benefit from GLP-1s if bought at production cost, but who cannot afford to pay $400 or $1,000 a month. Nor can even the government afford it, at this scale. Since 40% of Americans are obese and these drugs also help with other conditions, it might make sense to put 40% of Americans on GLP-1 drugs, instead of the roughly 10% currently on them.

The solution remains obvious. We should buy out the patents to such drugs.

This solves the consumption side. It removes the deadweight loss triangle from lost consumption. It removes the hardship of those who struggle to pay, as we can then allow generic competition to do its thing and charge near marginal cost. It would be super popular. It uses government’s low financing costs to provide locked-in up front cold hard cash to Novo Nordisk, presumably the best way to get them and others to invest the maximum in more R&D.

There are lots of obvious gains here, for on the order of $100 billion. Cut the check.

GLP-1 drugs linked to drop in opioid overdoses. Study found hazard ratios from 0.32 to 0.58, so a decline in risk of between roughly half and two-thirds.

GLP-1 drugs also reduce Alzheimer’s 40%-70% in patients with Type 2 Diabetes? This is a long term effect, so we don’t know if this would carry over to others yet.

This Nature post looks into theories of why GPL-1 drugs seem to help with essentially everything.

If you don’t want to do GLP-1s and you can’t date a sufficiently attractive person, here’s a claim that Keto Has Clearly Failed for Obesity, suggesting that people try keto, low-fat and protein restriction in sequence in case one works for you. Alas, the math here is off, because the experimenter is assuming non-overlapping ‘works for me’ groups (if anything I suspect positive correlation!), so no even if the other %s are right that won’t get you to 80%. The good news is if things get tough you can go for the GLP-1s now.

Bizarre freak that I am on many levels, I’m now building muscle via massive intake of protein shakes, regular lifting workouts to failure and half an hour of daily cardio, and otherwise down to something like 9-10 meals in a week. It is definitely working, but I’m not about to recommend everyone follow in my footsteps. This is life when you are the Greek God of both slow metabolism and sheer willpower.

Aella asks the hard questions. Such as:

Aella: I’ve mostly given up on trying to force myself to eat vegetables and idk my life still seems to be going fine. Are veggies a psyop? I’ve never liked them.

Jim Babcock: Veggies look great in observational data because they’re the lowest-priority thing in a sort of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Foods. People instinctively prioritize: first get enough protein, then enough calories, then enough electrolytes, then… if you don’t really need anything, veg.

Eric Schmidt: Psyop.

Psyop. You do need fiber one way or another. And there are a few other ways they seem helpful, and you do need a way to fill up without consuming too many calories. But no, they do not seem in any way necessary, you can absolutely go mostly without them. You’ll effectively pick up small amounts of them anyway without trying.

The key missing element in public health discussions of food, and also discussions of everything else, of course joy and actual human preferences and values.

Stian Westlake: I read a lot of strategies and reports on obesity and health, and it’s striking how few of them mention words like conviviality or deliciousness, or the idea that food is a source of joy, comfort and love.

Tom Chivers: this is such a common theme in public health. You need a term in your equation for the fact that people enjoy things – drinking, eating sweets, whatever – or they look like pure costs with no benefit whatsoever, so the seemingly correct thing to do will always be to reduce them.

Anders Sandberg: The Swedish public health authority recommended reducing screen usage among young people in a report that carefully looked at possible harms, but only cursorily at what the good sides were.

In case you were wondering if that’s a strawman, here’s Stian’s top response:

Mark: Seeing food as a “source of joy, comfort and love?” That mindset sounds like what would be used to rationalize unhealthy choices with respect to quantity and types of food. It sounds like a mantra for obesity.

Food is absolutely one of life’s top sources of joy, comfort and love. People downplay it, and some don’t appreciate it, but it’s definitely top 10, and I’d say it’s top 5. And maybe not overall but on some days, especially when you’re otherwise down or you put in the effort, it can absolutely 100% be top 1.

If I had to choose between ‘food is permanently joyless and actively sad, although not torture or anything, but you’re fit and healthy’ and ‘food is a source of joy, comfort and love, but you don’t feel so good about yourself physically and it’s not your imagination’ then I’d want to choose the first one… but I don’t think the answer is as obvious as some people think, and I’m fortunate I didn’t have to fully make that choice.

One potential fun way to get motivated is to date someone more attractive. Women who are dating more attractive partners had more motivation for losing weight, in the latest ‘you’ll never believe what science found’ study. Which then gets described, because it is 2024, as ‘there might be social factors playing a role in women’s disordered eating’ and an ‘ugly truth’ rather than ‘people respond to incentives.’

Carmen claims that to get most of the nutrients from produce what matters is time from harvest to consumption, while other factors like price and being organic matter little. And it turns out Walmart (!) does better than grocery stores on getting the goods to you in time, while farmers markets can be great but have large variance.

This also suggests that you need to consume what you buy quickly, and that buying things not locally in season should be minimized. If you’re eating produce for its nutrients, then the dramatic declines in average value here should make you question that strategy, and they he say that on this front frozen produce does as well or better on net versus fresh. There are of course other reasons.

It also reinforces the frustration with our fascination over whether a given thing is ‘good for you’ or not. There’s essentially no way to raise kids without them latching onto this phrase, even if both parents know better. Whereas the actual situation is super complicated, and if you wanted to get it right you’d need to do a ton of research on your particular situation.

My guess is Mu. It would be misleading to say either they were or were not a scam.

Aella: I think vegetables might be a scam. I hate them, and recently stopped trying to make myself eat them, and I feel fine. No issues. Life goes on; I am vegetable-free and slightly happier.

Rick the Tech Dad: Have you ever tried some of the fancier stuff? High quality Brussels sprouts cooked in maple syrup with bacon? Sweet Heirloom carrots in a sugar glaze? Chinese broccoli in cheese sauce?

Aella: Carrots are fine. The rest is just trying to disguise terrible food by smothering it in good food.

I have been mostly ‘vegetable-and-fruit-free’ for over 30 years, because:

-

If I try to eat most vegetables or fruits of any substantial size, my brain decides that what I am consuming is Not Food, and this causes me to increasingly gag with the size and texture of the object involved.

-

To the extent I do manage to consume such items in spite of this issue, in most cases those objects bring me no joy at all.

-

When they do bring me any joy or even the absence of acute suffering, this usually requires smothering them such that most calories are coming from elsewhere.

-

I do get exposure from some sauces, but mostly not other sources.

-

This seems to be slowly improving over the last ~10 years, but very slowly.

-

I never noticed substantial ill-effects and I never got any cravings.

-

To the extent I did have substantial ill-effects, they were easily fixable.

-

The claims of big benefits or trouble seem based on correlations that could easily not be causal. Obviously if you lecture everyone that Responsible People Eat Crazy Amounts of Vegetables well beyond what most people enjoy, and also they fill up stomach space for very few calories and thus reduce overall caloric consumption, there’s going to be very positive correlations here.

-

All of nutrition is quirky at best, everyone is different and no one knows anything.

-

Proposed actions in response to the problem tend to be completely insane asks.

People will be like ‘we have these correlational studies so you should change your entire diet to things your body doesn’t tell you are good and that bring you zero joy.’

I mean, seriously, fthat s. No.

I do buy that people have various specific nutritional requirements, and that not eating vegetables and fruits means you risk having deficits in various places. The same is true of basically any exclusionary diet chosen for whatever reason, and especially true for e.g. vegans.

In practice, the only thing that seems to be an actual issue is fiber.

Government assessments of what is healthy are rather insane on the regular, so this is not exactly news, but when Wagyu ground beef gets a D and Fruit Loops get a B, and McDonald’s fries get an A, you have a problem.

Yes, this is technically a ‘category based system’ but that only raises further questions. Does anyone think that will in practice help the average consumer?

I see why some galaxy brained official might think that what people need to know is how this specific source of ground beef compares to other sources of ground beef. Obviously that’s the information the customer needs to know, says this person. That person is fruit loops and needs to watch their plan come into contact with the enemy.

Bryan Johnson suggests that eating too close to bed is bad for your sleep, and hence for your health and work performance.

As with all nutritional and diet advice, this seems like a clear case of different things working differently for different people.

And I am confident Bryan is stat-maxing sleep and everything else in ways that might be actively unhealthy.

It is however worth noticing that the following are at least sometimes true, for some people:

Bryan Johnson:

-

Eating too close to bedtime increases how long you’re awake at night. This leads you to wanting to stay in bed longer to feel rested.

-

High fat intake before bed can lower sleep efficiency and cause a longer time to fall asleep. Late-night eating is also associated with reduced fatty acid oxidation (body is less efficient at breaking down fats during sleep). Also can cause weight gain and potentially obesity if eating patterns are chronic.

-

Consuming large meals or certain foods (spicy or high-fat foods) before bed can cause digestive issues like heartburn, which can disrupt sleep.

-

Eating late at night can interfere with your circadian rhythm, negatively effecting sleep patterns.

-

Eating late is asking the body to do two things at the same time: digest food and run sleep processes. This creates a body traffic jam.

-

Eating late can increase plasma cortisol levels, a stress hormone that can further affect metabolism and sleep quality.

What to do:

-

Experiment with eating earlier. Start with your last meal of the day 2 hours before bed and then try to 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours.

-

Experiment with eating different foods and build intuition. For me, things like pasta, pizza and alcohol are guaranteed to wreck my sleep. If I eat steamed veggies or something similarly light hours before bed sometimes, I usually don’t see any negative effects.

-

Measure your resting heart rate before bed. After years of working to master high quality sleep, my RHR before bed is the single strongest predictor of whether I’ll get high quality or low quality sleep. Eating earlier will lower your RHR at bedtime.

-

If you’re out late with friends or family, feel free to eat for the social occasion. Just try to light foods lightly.

I’ve run a natural version of this experiment, because my metabolism is so slow that I don’t ever eat three meals in a day. For many years I almost never ate after 2pm. For the most recent 15 years or so, I’ll eat dinner on Fridays with the family, and maybe twice a month on other days, and that’s it.

When I first wrote this section, I had not noticed a tendency to have worse sleep on Fridays, with the caveat that this still represents a minimum of about four hours before bed anyway since we rarely eat later than 6pm.

Since then, I have paid more attention, and I have noticed the pattern. Yes, on days that I eat lunch rather than dinner, or I eat neither, I tend to sleep better, in a modest but noticeable way.

I have never understood why you would want to eat dinner at 8pm or 9pm in any case – you’ve gone hungry the whole day, and now when you’re not you don’t get to enjoy that for long. Why play so badly?

The other tendency is that if you eat quite a lot, it can knock you out, see Thanksgiving. Is that also making your sleep worse? That’s not how I’d instinctively think of it, but I can see that point of view.

What about the other swords in the picture?

-

Screen time has never bothered me, including directly before sleep. Indeed, watching television is my preferred wind-down activity for going to sleep. Overall I get tons of screen time and I don’t think it matters for this.

-

I never drink alcohol so I don’t have any data on that one.

-

I never drink large amounts of caffeine either, so this doesn’t matter much either.

-

Healthier food, and less junk food, are subjective descriptions, with ‘less sugar’ being similar but better defined. I don’t see a large enough effect to worry about this until the point where I’m getting other signals that I’ve eaten too much sugar or other junk food. At which point, yes, there’s a noticeable effect, but I should almost never be doing that anyway.

-

Going to bed early is great… when it works. But if you’re not ready, it won’t work. Mostly I find it’s more important to not stay up too late.

-

But also none of these effects are so big that you should be absolutist about it all.

Physical activity is declining, so people spend less energy, and this is a substantial portion of why people are getting fatter. Good news is this suggests a local fix.

That is also presumably the primary cause of this result?

We now studied the Total energy expenditure (TEE) of 4799 individuals in Europe and the USA between the late 1980s and 2018 using the IAEA DLW database. We show there has been a significant decline in adjusted TEE over this interval of about 7.7% in males and 5.6% in females.

We are currently expending about 220 kcal/d less for males and 122 kcal/d less for females than people of our age and body composition were in the late 1980s. These changes are sufficient to explain the obesity epidemic in the USA.

What’s the best way to exercise and get in shape? Matt Yglesias points out that those who are most fit tend to be exercise enjoyers, the way he enjoys writing takes, whereas he and many others hate exercising. Which means if you start an exercise plan, you’ll probably fail. And indeed, I’ve started many exercise plans, and they’ve predictably almost all failed, because I hated doing them and couldn’t find anything I liked.

Ultimately what did work were the times I managed to finally figure out how to de facto be an exercise enjoyer and want to do it. A lot of that was finding something where the benefits were tangible enough to be motivating, but also other things, like being able to do it at home while watching television.

Unlike how I lost the weight, this one I do think mostly generalizes, and you really do need to just find a way to hack into enjoying yourself.

Here are some related claims about exercise, I am pretty sure Andrew is right here:

Diane Yap: I know this guy, SWE manager at a big tech company, Princeton grad. Recently broke up with a long term gf. His idea on how to get back in the dating market? Go to the gym and build more muscles. Sigh. I gave him a pep talk and convinced him that the girls for which that would make a difference aren’t worth his time anyway.

ofir geller: it can give him confidence which helps with almost all women.

Diane Yap: Ah, well if that’s the goal I can do that with words and save him some time.

Andrew Rettek: The first year or two of muscle building definitely improves your attractiveness. By the time you’re into year 5+ the returns on sexiness slow down or go negative across the whole population.

As someone who is half a year into muscle building for health, yes it quite obviously makes you more attractive and helps you feel confident and sexy and that all helps you a lot on the dating market, and also in general.

The in general part is most important.

Whenever someone finally does start lifting heavy things in some form, or even things like walking more, there is essentially universal self-reporting that the returns are insanely great. Almost everyone reports feeling better, and usually also looking better, thinking better and performing better in various ways.

It’s not a More Dakka situation, because the optimal amount for most people does not seem crazy high. It does seem like not a hard decision.

Exercise and weight training is the universal miracle drug. It’s insane to talk someone out of it. But yes, like anything else there are diminishing returns and you can overdose, and the people most obsessed with it do overdose and it actively backfires, so don’t go nuts. That seems totally obvious.

A plurality of Americans (45%) now correctly believe alcohol in moderation is bad for your health, versus 43% that think it makes no difference and 8% that think it is good.

It was always such a scam telling people that they needed to drink ‘for their health.’

I am not saying that there are zero situations in which it is correct to drink alcohol.

I would however say that if you think it falls under the classification of: If drinking seems like a good idea, it probably isn’t, even after accounting for this rule.

I call that Finkel’s Law. It applies here as much as anywhere.

My basic model is: Exercise and finding ways to actually do it matters. Finding a way to eat a reasonable amount without driving yourself crazy or taking the joy out of life, whether or not that involves Ozempic or another similar drug, matters, and avoiding acute deficits matters. Getting reasonable sleep matters. A lot of the details after that? They mostly don’t matter.

But you should experiment, be empirical, and observe what works for you in particular.