I bought “Remove Before Flight” tags on eBay in 2010—it turns out they’re from Challenger

40th anniversary of the Challenger tragedy

“This is an attempt to learn more…”

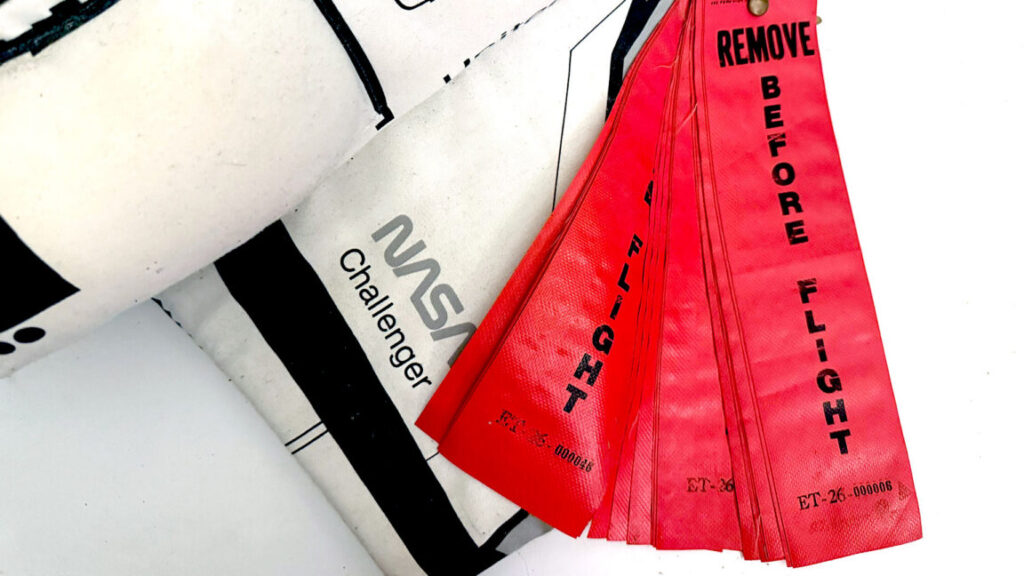

The stack of 18 “Remove Before Flight” tags as they were clipped together for sale on eBay in 2010. It was not until later that their connection to the Challenger tragedy was learned. Credit: collectSPACE.com

Forty years ago, a stack of bright red tags shared a physical connection with what would become NASA’s first space shuttle disaster. The small tags, however, were collected before the ill-fated launch of Challenger, as was instructed in bold “Remove Before Flight” lettering on the front of each.

What happened to the tags after that is largely unknown.

This is an attempt to learn more about where those “Remove Before Flight” tags went after they were detached from the space shuttle and before they arrived on my doorstep. If their history can be better documented, they can be provided to museums, educational centers, and astronautical archives for their preservation and display.

To begin, we go back 16 years to when they were offered for sale on eBay.

From handout to hold on

The advertisement on the auction website was titled “Space Shuttle Remove Before Flight Flags Lot of 18.” They were listed with an opening bid of $3.99. On January 12, 2010, I paid $5.50 as the winner.

At that point, my interest in the 3-inch-wide by 12-inch-long (7.6 by 30.5 cm) tags was as handouts for kids and other attendees at future events. Whether it was at an astronaut autograph convention, a space memorabilia show, a classroom visit, or a conference talk, having “swag” was a great way to foster interest in space history. At first glance, these flags seemed to be a perfect fit.

So I didn’t pay much attention when they first arrived. The eBay listing had promoted them only as generic examples of “KSC Form 4-226 (6/77)”—the ID the Kennedy Space Center assigned to the tags. There was no mention of their being used, let alone specifying an orbiter or specific flight. If I recall correctly, the seller said his intention had been to use them on his boat.

(Attempts to retrieve the original listing for this article were unsuccessful. As an eBay spokesperson said, “eBay does not retain transaction records or item details dating back over a decade, and therefore we do not have any information to share with you.”)

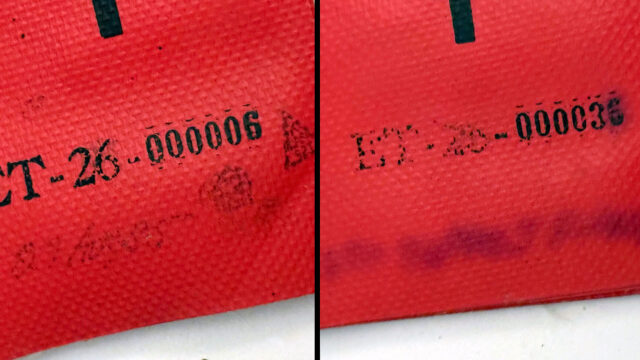

It was about a year later when I first noticed the ink stamps at the bottom of each tag. They were marked “ET-26” followed by a number. For example, the first tag in the clipped-together stack was stamped “ET-26-000006.”

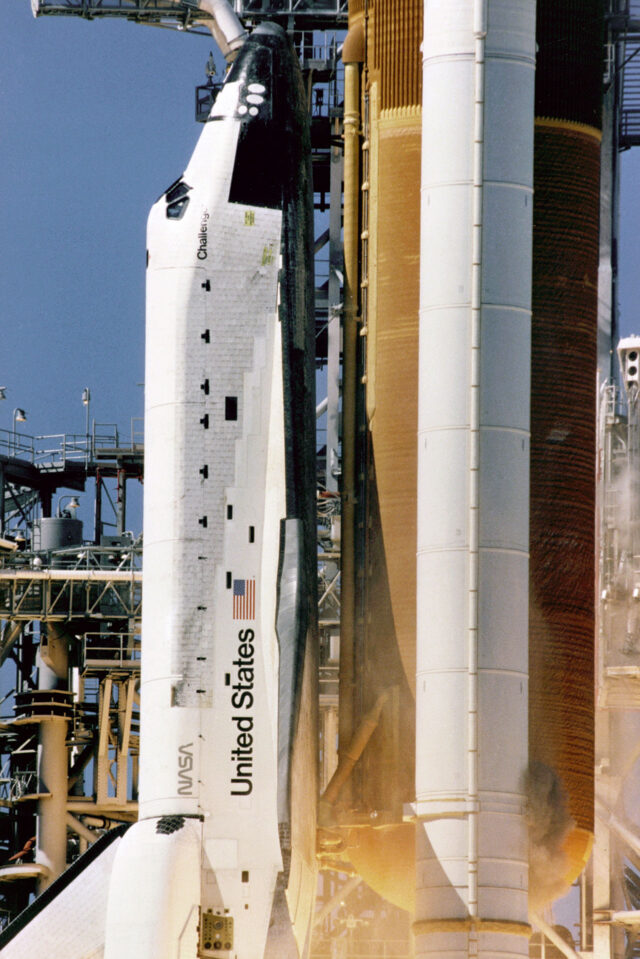

The same type of “Remove Before Flight” tags that were attached to ET-26 for Challenger‘s ill-fated STS-51L mission can be seen on one of the first two external tanks before it was flown, as distinguished by the insulation having been painted white. Credit: NASA via collectSPACE.com

“ET” refers to the External Tank. The largest components of the space shuttle stack, the burnt orange or brown tanks were numbered, so 26 had to be one of the earlier missions of the 30-year, 135-flight program.

A fact sheet prepared by Lockheed Martin provided the answer. The company operated at the Michoud Assembly Facility near New Orleans, where the external tanks were built before being barged to the Kennedy Space Center for launch. Part of the sheet listed each launch with its date and numbered external tank. As my finger traced down the page, it came to STS 61-B, 11/26/85, ET-22; STS 61-C, 1/12/86, ET-30; and then STS 51-L, 1/28/86… ET-26.

Removed but still connected

To be clear, the tags had no role in the loss of Challenger or its crew, including commander Dick Scobee; pilot Mike Smith; mission specialists Ronald McNair, Judith Resnik, and Ellison Onizuka; payload specialist Gregory Jarvis; and Teacher-in-Space Christa McAuliffe. Although the structural failure of the external tank ultimately resulted in Challenger breaking apart, it was a compromised O-ring seal in one of the shuttle’s two solid rocket boosters that allowed hot gas to burn through, impinging the tank.

Further, although it’s still unknown when the tags and their associated ground support equipment (e.g., protective covers, caps) were removed, it was not within hours of the launch, and in many cases, it was completed well before the vehicle reached the pad.

“They were removed later in processing at different times but definitely all done before propellant loading,” said Mike Cianilli, the former manager of NASA’s Apollo, Challenger, Columbia Lessons Learned Program. “To make sure they were gone, final walkdowns and closeouts by the ground crews confirmed removal.”

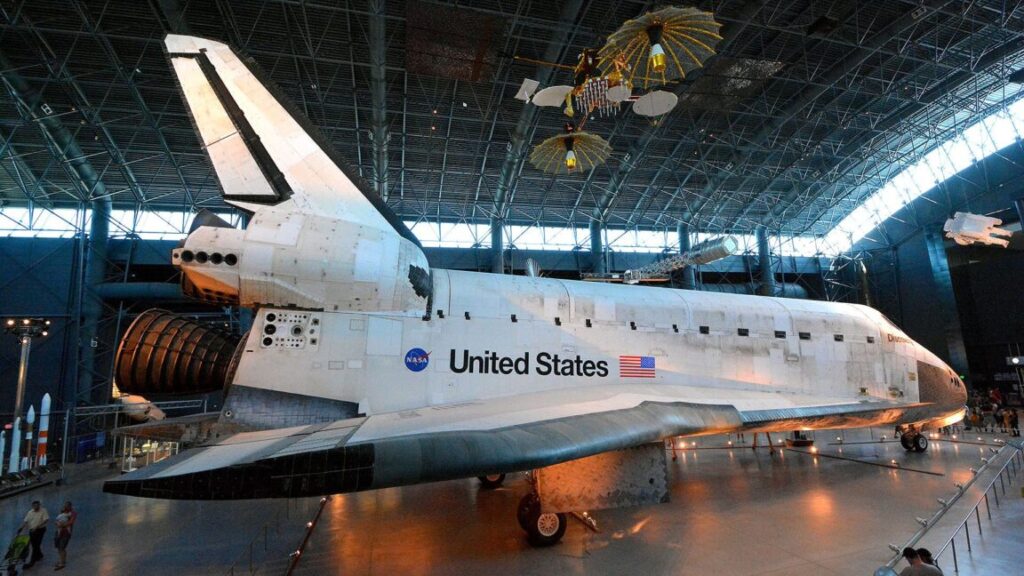

Close-up view of the liftoff of the space shuttle Challenger on its ill-fated last mission, STS-51L. A cloud of grey-brown smoke can be seen on the right side of the solid rocket booster on a line directly across from the letter “U” in United States. This was the first visible sign that an SRB joint breach may have occurred, leading to the external tank (ET-26) being compromised during its ascent.

Credit: NASA

Close-up view of the liftoff of the space shuttle Challenger on its ill-fated last mission, STS-51L. A cloud of grey-brown smoke can be seen on the right side of the solid rocket booster on a line directly across from the letter “U” in United States. This was the first visible sign that an SRB joint breach may have occurred, leading to the external tank (ET-26) being compromised during its ascent. Credit: NASA

According to NASA, approximately 20 percent of ET-26 was recovered from the ocean floor after the tragedy, and like the parts of the solid rocket boosters and Challenger, they were placed into storage in two retired missile silos at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (today, Space Force Station). Components removed from the vehicle before the ill-fated launch that were no longer needed likely went through the normal surplus processes as overseen by the General Services Administration, said Cianilli.

Once the tags’ association with STS-51L was confirmed, it no longer felt right to use them as giveaways. At least, not to individuals.

There are very few items directly connected to Challenger‘s last flight that museums and other public centers can use to connect their visitors to what transpired 40 years ago. NASA has placed only one piece of Challenger on public display, and that is in the exhibition “Forever Remembered” at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.

Each of the 50 US states, the Smithsonian, and the president of the United States were also presented with a small American flag and a mission patch that had been aboard Challenger at the time of the tragedy.

Having a more complete history of these tags would help meet the accession requirements of some museums and, if approved, provide curators with the information they need to put the tags on display.

Reconnecting to flight

When the tags were first identified, contacts at NASA and Lockheed, among others, were unable to explain how they ended up on eBay and, ultimately, with me.

It was 2011, and the space shuttle program was coming to its end. I was politely told that this was not the time to ask about the tags, as documents were being moved into archives and, perhaps more importantly, people were more concerned about pending layoffs. One person suggested the tags be put back in a drawer and forgotten about for another decade.

In the years since, other “Remove Before Flight” tags from other space shuttle missions have come up for sale. Some have included evidence that the tags had passed through the surplus procedures; some did not and were offered as is.

Close-up detail of two of the 18 shuttle “Return Before Flight” tags purchased off eBay. All were marked “ET-26” with a serial number. Some included additional stamps and handwritten notations. Most of the latter, though, has bled into the fabric to the point that it can no longer be read. Credit: collectSPACE.com

There were anecdotes about outgoing employees taking home mementos. Maybe someone saw these tags heading out as scrap (or worse, being tossed in the garbage) and, recognizing what they were, saved them from being lost to history. An agent with the NASA Office of Inspector General once said that dumpster diving was not prohibited, so long as the item(s) being dived for were not metal (due to recycling).

More recent attempts to reach people who might know anything about the specific tags have been unsuccessful, other than the few details Cianilli was able to share. An attempt to recontact the eBay seller has so far gone unanswered.

If you or someone you know worked on the external tank at the time of the STS-51L tragedy, or if you’re familiar with NASA’s practices regarding installing, retrieving, and archiving or disposing of the Remove Before Flight tags, please get in contact.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE, a daily news publication and online community focused on where space exploration intersects with pop culture. He is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of “Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He is on the leadership board for For All Moonkind and is a member of the American Astronautical Society’s history committee.