An in-space construction firm says it can help build massive data centers in orbit

There has been much discussion in the space community recently about building large data centers in orbit to avoid the environmental consequences of sprawling computing facilities on Earth. These space-based data centers could take advantage of the always-on, free fusion reactor at the center of the Solar System.

Proponents say this represents a natural step in the evolution of moving heavy industry off the planet’s surface and a solution for the ravenous energy needs of artificial intelligence. Critics say building data centers in space is technically very challenging and cite major hurdles, such as radiating away large amounts of heat and the cost of accessing space.

It is unclear who is right, but one thing is certain: Such facilities would need to be massive to support artificial intelligence.

That’s… a big solar array

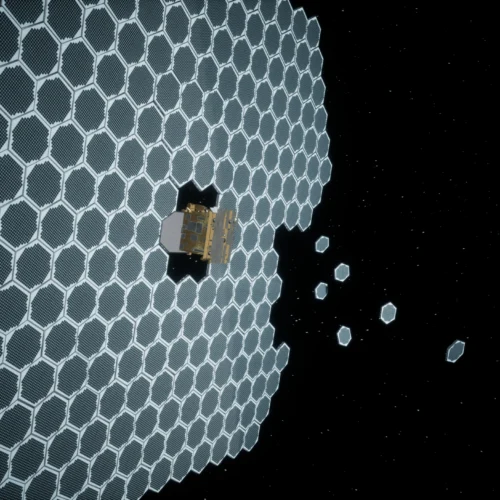

Nvidia recently made headlines by announcing that one of the companies it is partnering with, Starcloud, plans to build a 5-gigawatt orbital data center with “super-large solar and cooling panels approximately 4 kilometers in width and length.”

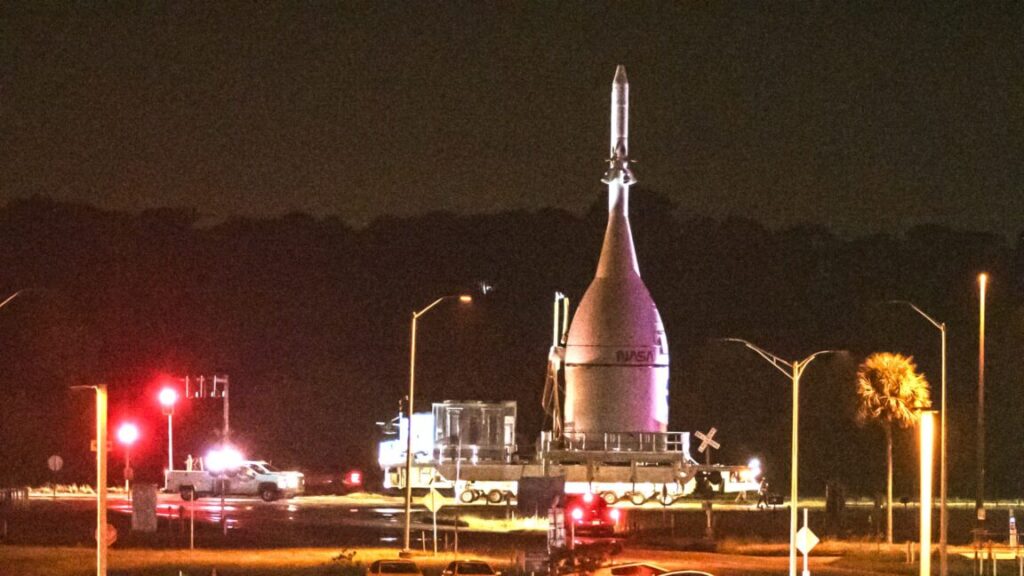

To put that into perspective, the eight main solar arrays on the International Space Station—the largest ever assembled in space, requiring many space shuttle launches and spacewalks—span about 100 meters and produce a maximum of about 240 kW. That’s about 0.005 percent of the power Starcloud intends to generate.

Needless to say, with a traditional approach, that’s a big ask in terms of launch and assembly costs.

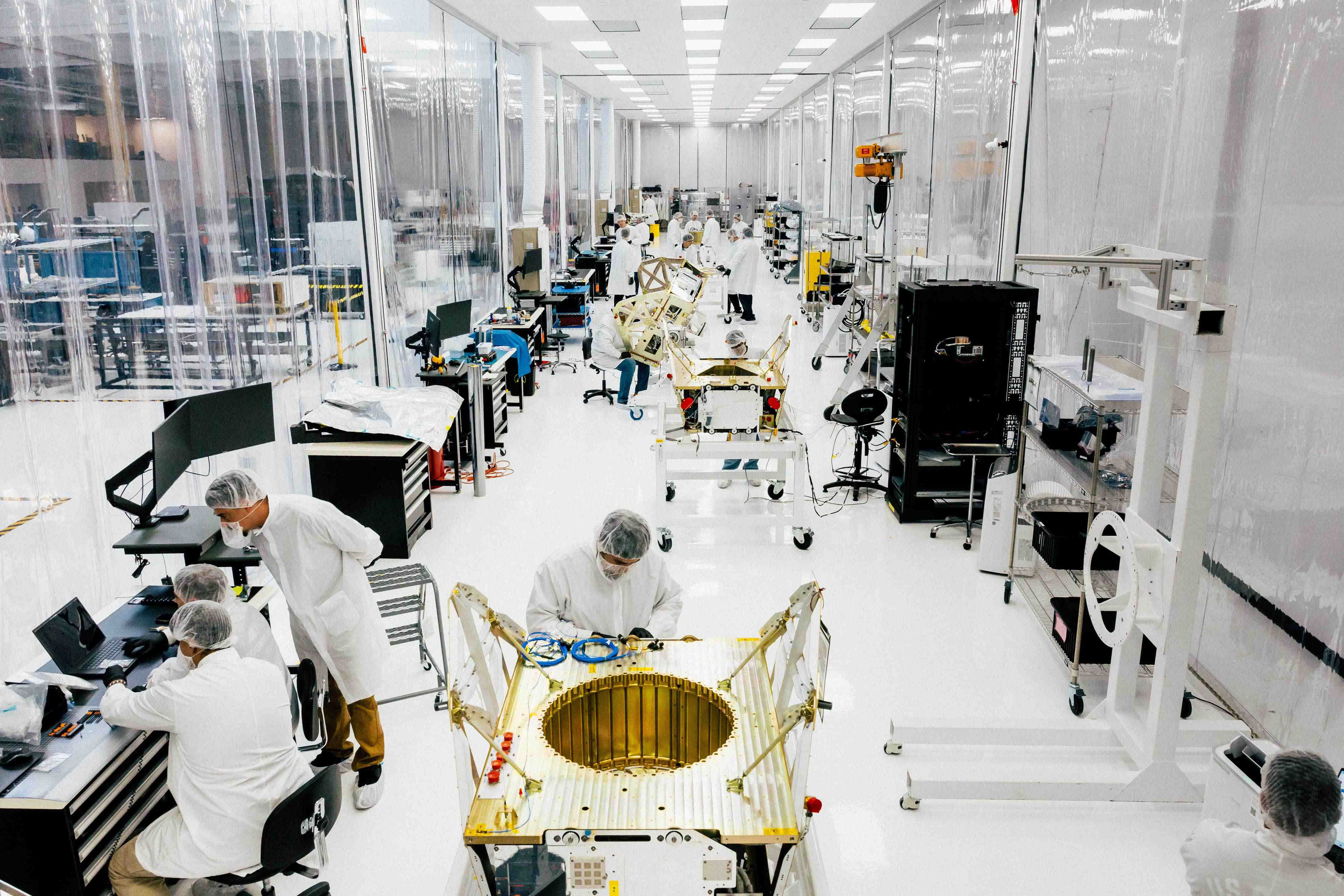

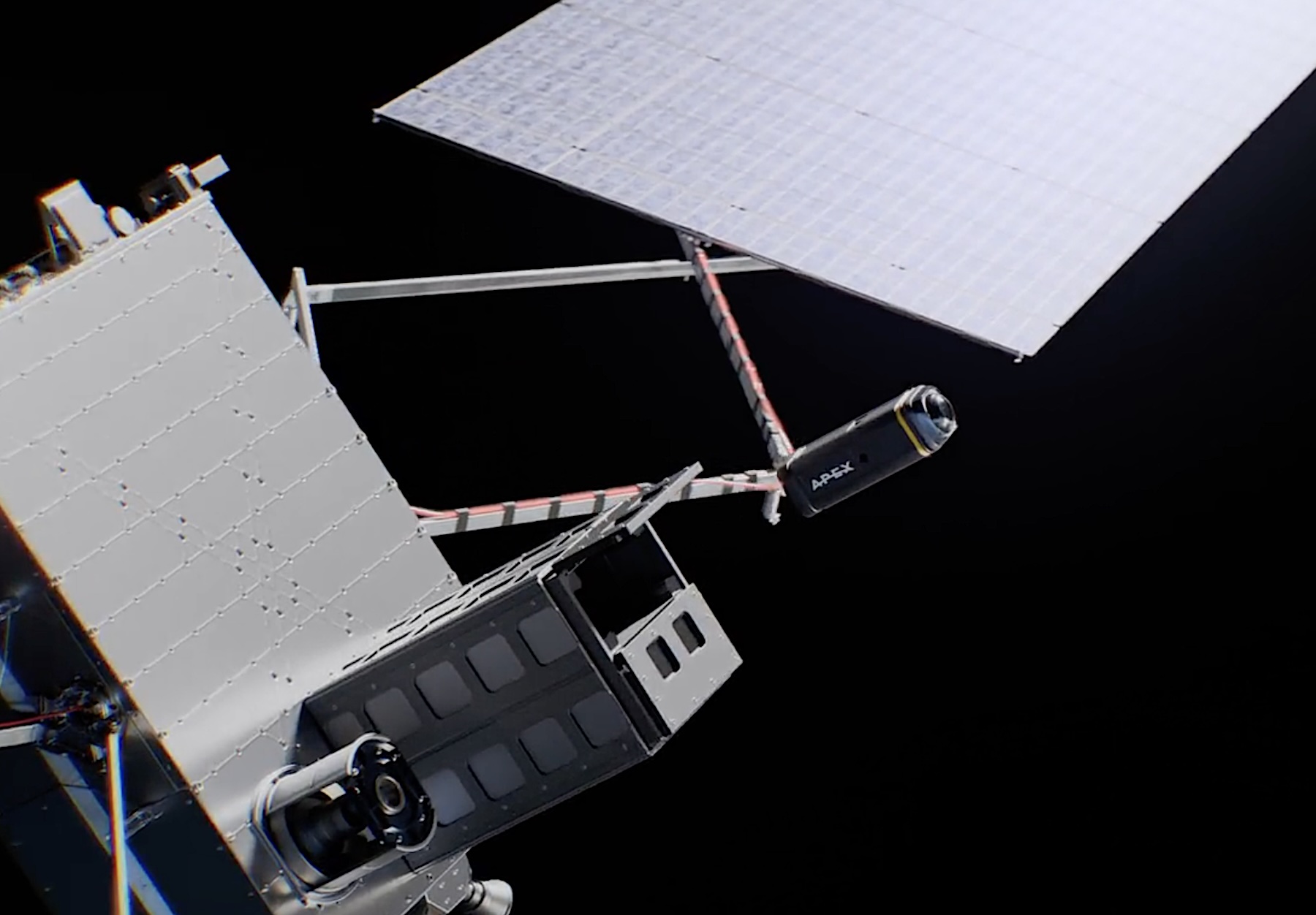

However, it sounds a little more feasible if such an array could be assembled autonomously. And on Thursday morning, Starcloud, along with a new in-space assembly company, Rendezvous Robotics, announced an agreement to explore the use of modular, autonomous assembly to build Starcloud’s data centers.

“Our mission is to build things that are going to be useful in space,” Phil Frank, chief executive of Rendezvous Robotics, told Ars. “It could be large, flat surfaces like a Solar array. Ostensibly, the size is not the limit anymore, because we can additively assemble things and then reconfigure them in orbit. And that’s the core thesis of our company that led to us talking to the Starcloud team.”

An in-space construction firm says it can help build massive data centers in orbit Read More »