NASA astronauts will have their own droid when they go back to the Moon

Artemis IV will mark the second lunar landing of the Artemis program and build upon what is learned at the moon’s south pole on Artemis III.

“After his voyage to the Moon’s surface during Apollo 17, astronaut Gene Cernan acknowledged the challenge that lunar dust presents to long-term lunar exploration. Moon dust sticks to everything it touches and is very abrasive,” read NASA’s announcement of the Artemis IV science payloads.

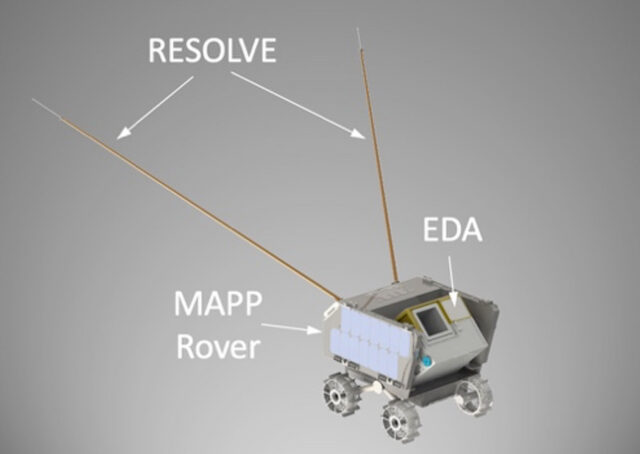

Rendering of Lunar Outpost’s MAPP lunar rover with its Artemis IV DUSTER science instruments, including the Electrostatic Dust Analyzer (EDA) and Relaxation SOunder and differentiaL VoltagE (RESOLVE). Credit: LASP/CU Boulder/Lunar Outpost

To that end, the solar-powered MAPP will support DUSTER (DUst and plaSma environmenT survEyoR), a two-part investigation from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado, Boulder. The autonomous rover’s equipment will include the Electrostatic Dust Analyzer (EDA), which will measure the charge, velocity, size, and flux of dust particles lofted from the lunar surface, and the RElaxation SOunder and differentiaL VoltagE (RESOLVE) instrument, which will characterize the average electron density above the lunar surface using plasma sounding.

The University of Central Florida and University of California, Berkeley, have joined with LASP to interpret measurements taken by DUSTER. The former will look at the dust ejecta generated during the Human Landing System (HLS, or lunar lander) liftoff from the Moon, while the latter will analyze upstream plasma conditions.

Lunar dust attaches to almost everything it comes into contact with, posing a risk to equipment and spacesuits. It can also obstruct solar panels, reducing their ability to generate electricity and cause thermal radiators to overheat. The dust can also endanger astronauts’ health if inhaled.

“We need to develop a complete picture of the dust and plasma environment at the lunar south pole and how it varies over time and location to ensure astronaut safety and the operation of exploration equipment,” said Xu Wang, senior researcher at LASP and principal investigator of DUSTER, in a University of Colorado statement. “By studying this environment, we gain crucial insights that will guide mitigation strategies and methods to enable long-term, sustained human exploration on the Moon.”

NASA astronauts will have their own droid when they go back to the Moon Read More »