Lull in Falcon Heavy missions opens window for SpaceX to build new landing pads

SpaceX’s goal for this year is 170 Falcon 9 launches, and the company is on pace to come close to this target. Most Falcon 9 launches carry SpaceX’s own Starlink broadband satellites into orbit. The FAA’s environmental approval opens the door for more flights from SpaceX’s busiest launch pad.

But launch pad availability is not the only hurdle limiting how many Falcon 9 flights can take off in a year. There’s also the rate of production for Falcon 9 upper stages, which are new on each flight, and the time it takes for each vessel in SpaceX’s fleet of drone ships (one in California, two in Florida) to return to port with a recovered booster and redeploy back to sea again for the next mission. SpaceX lands Falcon 9 boosters on offshore drone ships after most of its launches and only brings the rocket back to an onshore landing on missions carrying lighter payloads to orbit.

When a Falcon 9 booster does return to landing on land, it targets one of SpaceX’s recovery zones at military-run spaceports in Florida and California. SpaceX’s landing zone at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California is close to the Falcon 9 launch pad there.

The Space Force wants SpaceX, and potentially other future reusable rocket companies, to replicate the side-by-side launch and landing pads at Cape Canaveral.

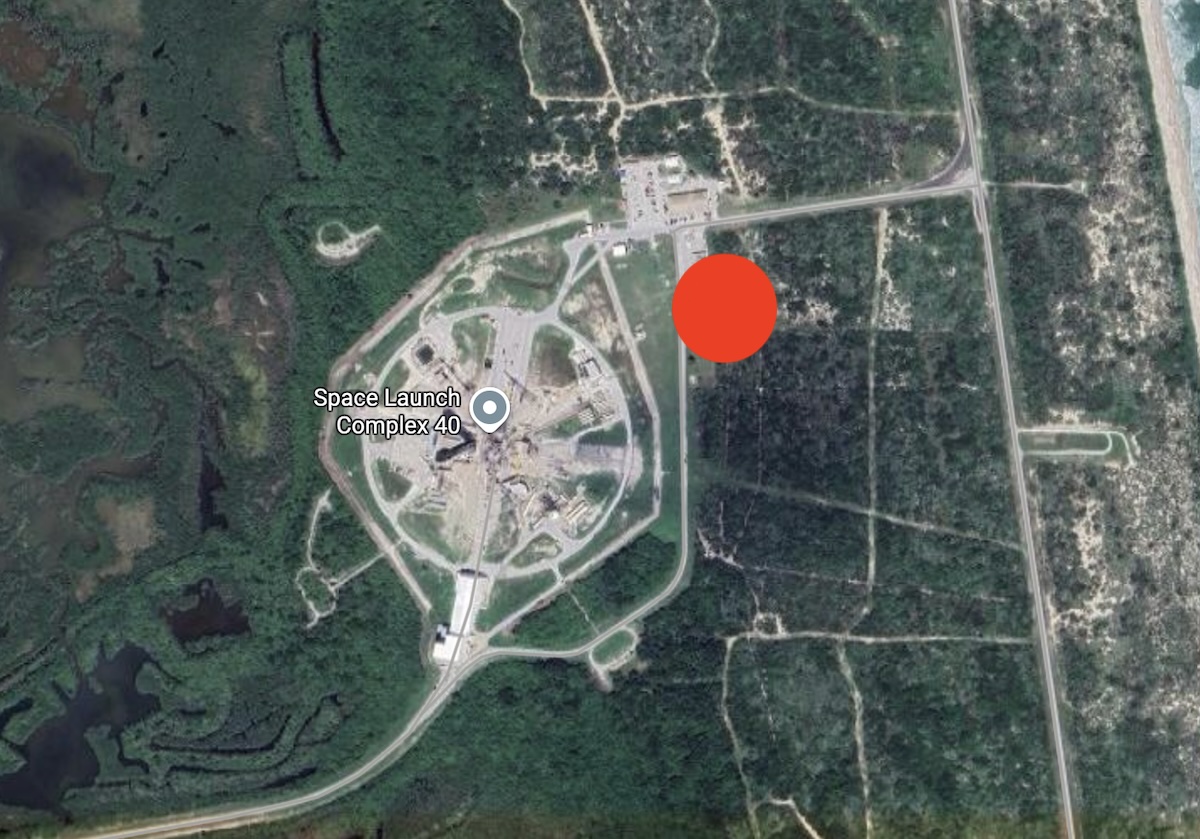

To do that, the FAA also gave the green light Wednesday for SpaceX to construct and operate a new rocket landing zone at SLC-40 and conduct up to 34 first-stage booster landings there each year. The landing zone will consist of a 280-foot diameter concrete pad surrounded by a 60-foot-wide gravel apron. The landing zone’s broadest diameter, including the apron, will measure 400 feet.

The location of SpaceX’s new rocket landing pad is shown with the red circle, approximately 1,000 feet northeast of the Falcon 9 rocket’s launch pad at Space Launch Complex-40. Credit: Google Maps/Ars Technica

SpaceX is in an earlier phase of planning for a Falcon landing pad at historic Launch Complex-39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, just a few miles north of SLC-40. SpaceX uses LC-39A as a launch pad for most Falcon 9 crew launches, all Falcon Heavy missions, and, in the future, flights of the company’s gigantic next-generation rocket, Starship. SpaceX foresees Starship as a replacement for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, but the company’s continuing investment in Falcon-related infrastructure shows the workhorse rocket will stick around for a while.

Lull in Falcon Heavy missions opens window for SpaceX to build new landing pads Read More »