Apple’s push to take over the dashboard resisted by car makers

Of the original 14 brands listed by Apple, Jaguar Land Rover said it was still evaluating the system, while Ford and Nissan along with its Infiniti brand said they had no information to share about future application.

According to a survey conducted by McKinsey in 2023, almost half the car buyers said they would not buy a vehicle that lacked Apple CarPlay or Android Auto, while 85 percent of car owners who have Apple CarPlay or a similar service preferred it over the auto group’s own built-in system.

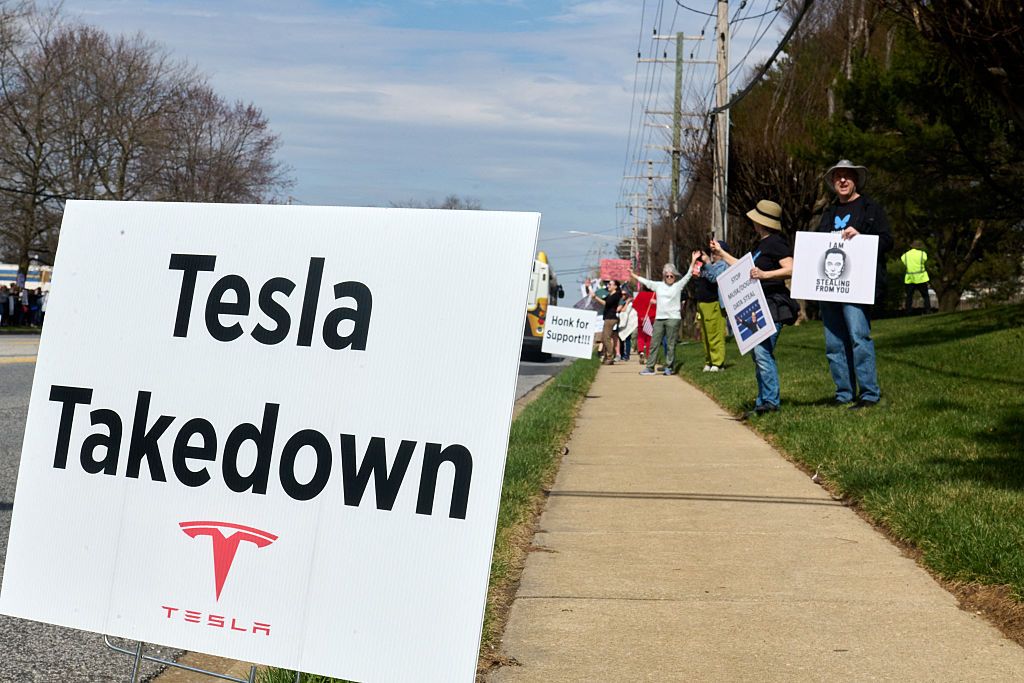

Credit: Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Many carmakers, including Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi, have developed infotainment and operating systems, but they would continue to offer the option of using standard Apple CarPlay to meet consumer demand. Apple said customers were going to like CarPlay Ultra, and carmakers would ultimately respond to consumer demand.

BMW said it would integrate the existing Apple CarPlay with its new design, while Audi said its focus was to offer drivers “a customized and seamless digital experience,” so it would not use CarPlay Ultra, although the standard version was available on its vehicles.

While Volvo Cars said there were no plans to use CarPlay Ultra, its chief executive, Håkan Samuelsson, said carmakers should not try to compete on software with technology companies. “There are others who can do that better, and then we should offer that in our cars,” he said.

Aston Martin integrated Apple’s CarPlay Ultra with its newly developed infotainment system but stressed that the design inside the car remained “unmistakably” Aston Martin. The traditional physical dials were also available for those who do not want to use the touchscreen, it said.

People close to the carmaker said discussions with Apple in integrating CarPlay Ultra involved setting clear lines on data sharing from the start. The use of CarPlay Ultra did not entail additional sharing of vehicle data, which is stored inside Aston Martin’s own infotainment system and software. Apple also said vehicle data was not shared with the iPhone.

Graphic illustration by Ian Bott; additional reporting by Harry Dempsey in Tokyo.

© 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

Apple’s push to take over the dashboard resisted by car makers Read More »