Tax credits for electric cars are no more. What’s next for the US EV industry?

Dozens of new models are in the pipeline.

It’s hard to avoid seeing a face here. Credit: Jonathan Gitlin

The end of US tax credits for buying electric vehicles has changed the market in ways that are still unfolding.

I spoke this week with people closely monitoring the auto industry to get a sense of what’s next. They said the loss of federal incentives is likely to dampen shoppers’ enthusiasm, but the upcoming arrival of several dozen new or redesigned models could help fuel a comeback.

“I think the dust needs to settle for everyone to figure out what’s going to happen near term,” said Stephanie Valdez Streaty, director of industry insights for Cox Automotive.

Until October 1, the federal government offered a tax credit of up to $7,500 for the purchase of a qualifying new EV, and $3,000 for a qualifying used EV. In addition, there was a $7,500 incentive available for new EV leases. Those are now gone with the passage in July of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which sought to undo clean energy policies as part of a larger package of tax cuts and spending.

EV sales surged in recent months as customers aimed to get the credits before they expired. Now, without the credits, sales are likely to drop this month and the rest of this year.

But automakers have taken steps to soften the blow. Ford and General Motors have said they will continue to offer a $7,500 credit on leases. They can do this because their in-house finance companies purchased the vehicles while the credits were still active and the companies can pass on the savings to consumers, even after October 1.

Hyundai is offering a promotion in which it is selling and leasing its 2026 Ioniq 5 with price cuts of up to $9,800, effectively providing the equivalent of the tax credit and then some.

Also, some state and local governments are increasing their incentives for buying EVs. For example, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis last week announced that the state is increasing its tax credit from $6,000 to $9,000 for buying or leasing a new EV.

The promotions by automakers are likely to contribute to a “soft landing” for EV sales, said Ed Kim, president and chief analyst at AutoPacific, a research firm.

“We’ve hit a massive speed bump,” he said. “But I do firmly believe that electrification is the future, and you can’t stop the future, especially when the rest of the world is heading that way.”

He is referring to how China and the European Union have outpaced the United States in terms of electrifying their transportation sectors.

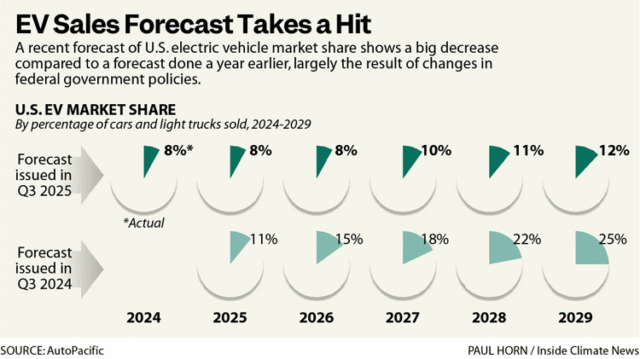

According to AutoPacific’s most recent forecast, EV market share in the United States is expected to remain at 8 percent in 2025 and 2026, the same as it was in 2024. This represents a decrease from the firm’s estimate last year, when it predicted market share would reach 11 percent in 2025 and 15 percent in 2026.

Credit: Inside Climate News

While the current situation is not ideal for anyone who wants to see broad EV adoption, the forecast indicates that the market will hold its own despite the end of the tax credits, Kim said.

Keith Barry, who covers autos for Consumer Reports, had a similar sentiment about how life will go on for the US EV market.

“We don’t know what happens next, but I suspect that Oct. 1 won’t be the ‘end of the world’ for EV deals,” he said in an email. “Some automakers found a way to extend tax credits on leases for some in-stock EVs until the end of the year. Other automakers ramped up production in expectation of the tax credit being around until 2032, and now they have too much stock and have to price their vehicles accordingly.”

Barry’s main advice for EV buyers is similar to what it was when tax credits were still around. First, he thinks people should consider leasing an EV rather than buying one.

“The technology is changing so fast that you don’t want to get stuck with a model that’s out of date and that has depreciated accordingly,” he said. “With a lease, that’s not your problem.”

Second, Barry recommends that shoppers choose a model that has been on the market for a few years. In his experience, newly designed cars have growing pains and tend to become more reliable after the first model year.

To gain insight into how EV companies view this moment, I got in touch with the Zero Emission Transportation Association, an advocacy group for auto manufacturers, battery makers, and others that support the growth of the EV economy. Corey Cantor, the group’s research director, said this is a good time to focus on consumer education about the benefits of EVs, such as lower fuel and maintenance costs.

He described this as “getting back to basics of making electric vehicles and the industry more understood by the mass market.” Such an approach makes sense, he said, because the cars continue to improve and some of the main obstacles—such as concerns about battery range and access to charging stations—are diminishing as batteries improve and the charging infrastructure expands.

About three dozen new or redesigned EVs are coming on the market later this year and next year. This reflects automakers’ continuing ramp-up of their EV lineups, and that the companies were putting together their plans for 2025 and 2026 before they had much of an inkling that the tax credits would be canceled.

For perspective, the new models will mean that shoppers will have about 50 percent more EV options than they currently have. (I’m basing this percentage on Cox Automotive’s list of current EV models.)

I asked each of the people I interviewed this week which models they thought have the potential to be great cars, strong sellers, or both.

Valdez Streaty is eager to see the Rivian R2, a mid-size SUV set to begin production next year, with a starting price of about $45,000, which is much lower than other vehicles in the company’s lineup.

She has high expectations for the new version of the Chevrolet Bolt hatchback, which is set to begin production late this year after a three-year break. The updated version uses General Motors’ Ultium battery platform and is likely to have a starting price in the $35,000 range.

The new Bolt “could be really good for the industry, since it’s a good price point,” she said.

She’s hinting at the larger question of which upcoming model will appeal to a mass market because of a combination of an affordable price and compelling features.

“The new Nissan Leaf is one to watch,” said Barry of Consumer Reports.

The next-generation Leaf will go on sale this year with a starting price of $29,990. Previous versions were affordable but often lacking in range and features. This one has a listed range of 303 miles, which is a lot for an entry-level model.

Kim is eager to see how customers respond to the Subaru Trailseeker, which is set to go on sale next year with a price likely to be in the $50,000 range.

Guests look at the 2026 Subaru Trailseeker after it was unveiled during a press preview at the New York International Auto Show in New York City on April 16. Credit: Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images

“It’s basically an electric Outback,” he said, referring to one of Subaru’s top-selling and best-known models.

He noted that Subaru has often appealed to consumers who are also likely to be open to buying an EV. So, if the brand ever produces a compelling EV, it should have an eager audience.

I haven’t yet mentioned Tesla, the country’s leading EV brand, which has suffered through declining sales and harmed its image because of CEO Elon Musk’s close association with the Trump administration.

On Tuesday, Tesla announced the introduction of the Model 3 Standard and Model Y Standard, which are more affordable versions of the company’s top two models.

The Model 3 Standard has a base price of $36,990, which is $5,500 less than the Model 3 Premium. The Model Y Standard sells for $39,990, which is $5,000 less than the Model Y Premium.

To reduce the prices, Tesla took steps to cut costs. One notable difference is that the Model Y Standard’s glass roof is only on the outside of the car, while the inside is a solid headliner of sound-absorbing material, creating an effect which Car and Driver describes as “pulling a ‘Cask of Amontillado’ and sealing occupants off from the panoramic glass above.”

Is the lower price going to boost Tesla’s sales and offset the effects of losing tax credits?

It may help a little, but Kim is mostly unimpressed.

“I see it as a post-credit price correction more than anything else,” he said.

Even with a lower price, he thinks the Model Y compares unfavorably in terms of cost and features with the Ioniq 5.

And, as several people have observed this week, Tesla’s price cuts aren’t enough to offset the effect of losing the tax credit, underscoring how the loss of the credit is like a sad trombone playing in the background.

This story originally appeared on Inside Climate News.

Tax credits for electric cars are no more. What’s next for the US EV industry? Read More »