The military’s squad of satellite trackers is now routinely going on alert

“I hope this blows your mind because it blows my mind.”

A Long March 3B rocket carrying a new Chinese Beidou navigation satellite lifts off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center on May 17, 2023. Credit: VCG/VCG via Getty Images

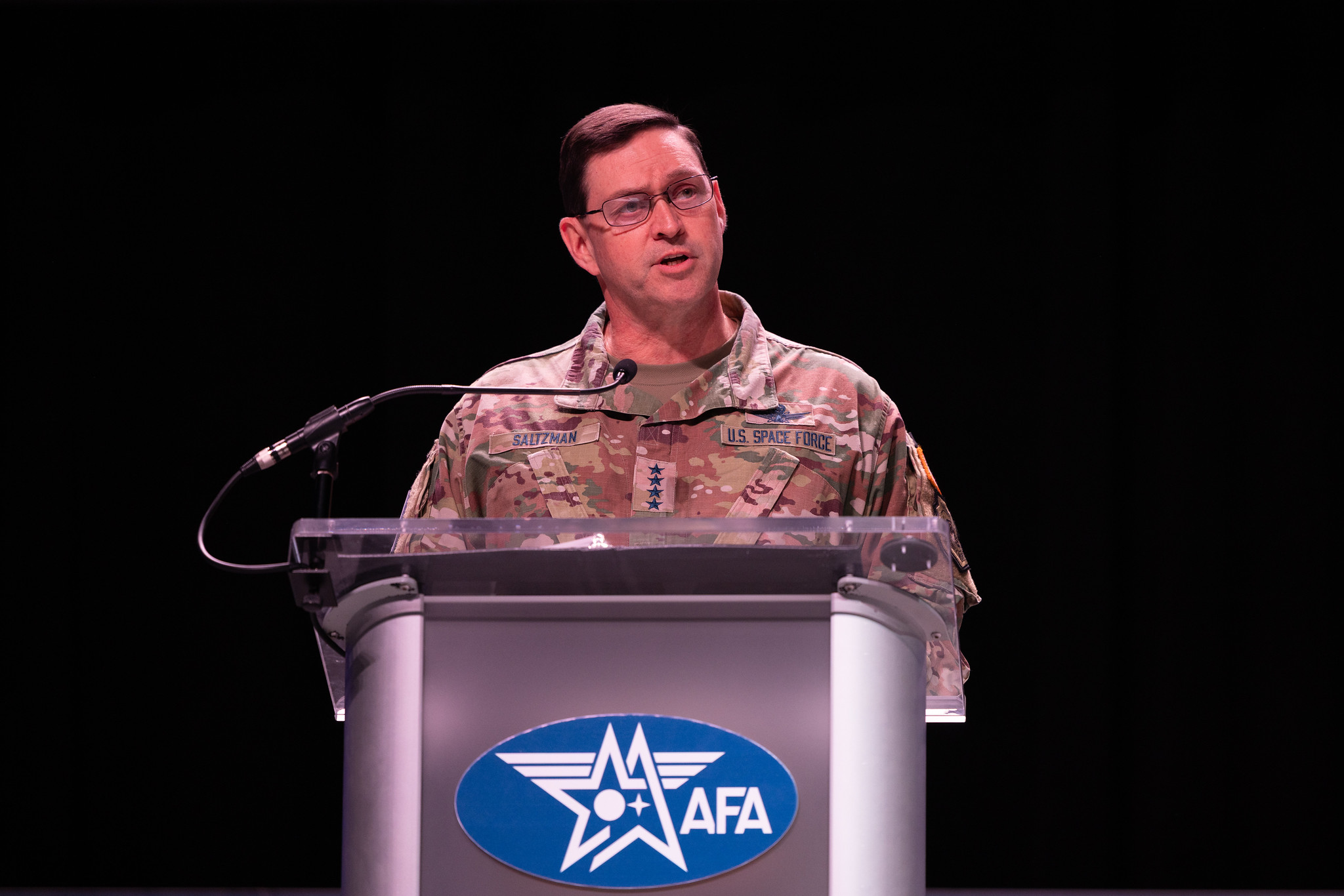

This is Part 2 of our interview with Col. Raj Agrawal, the former commander of the Space Force’s Space Mission Delta 2.

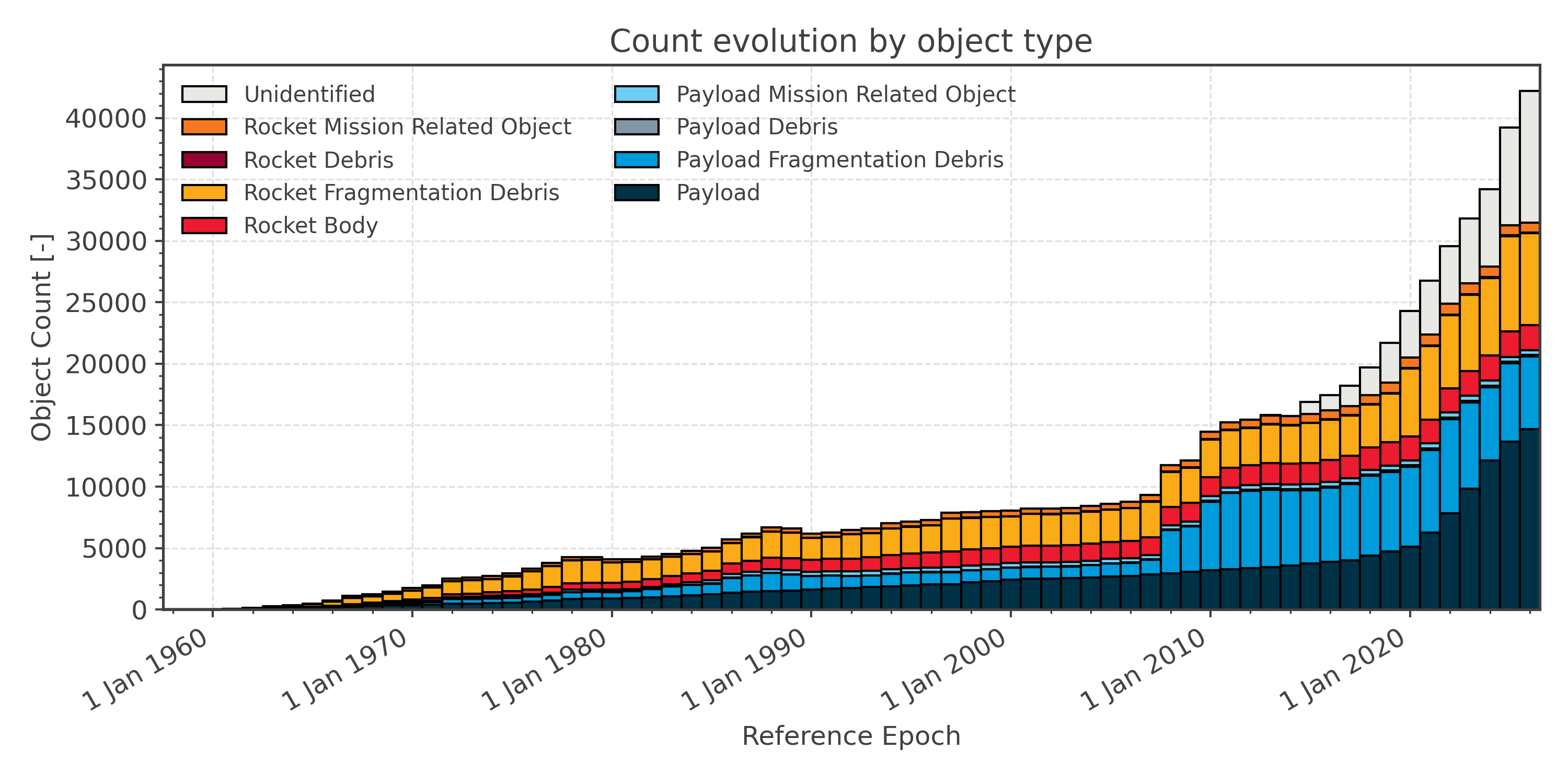

If it seems like there’s a satellite launch almost every day, the numbers will back you up.

The US Space Force’s Mission Delta 2 is a unit that reports to Space Operations Command, with the job of sorting out the nearly 50,000 trackable objects humans have launched into orbit.

Dozens of satellites are being launched each week, primarily by SpaceX to continue deploying the Starlink broadband network. The US military has advance notice of these launches—most of them originate from Space Force property—and knows exactly where they’re going and what they’re doing.

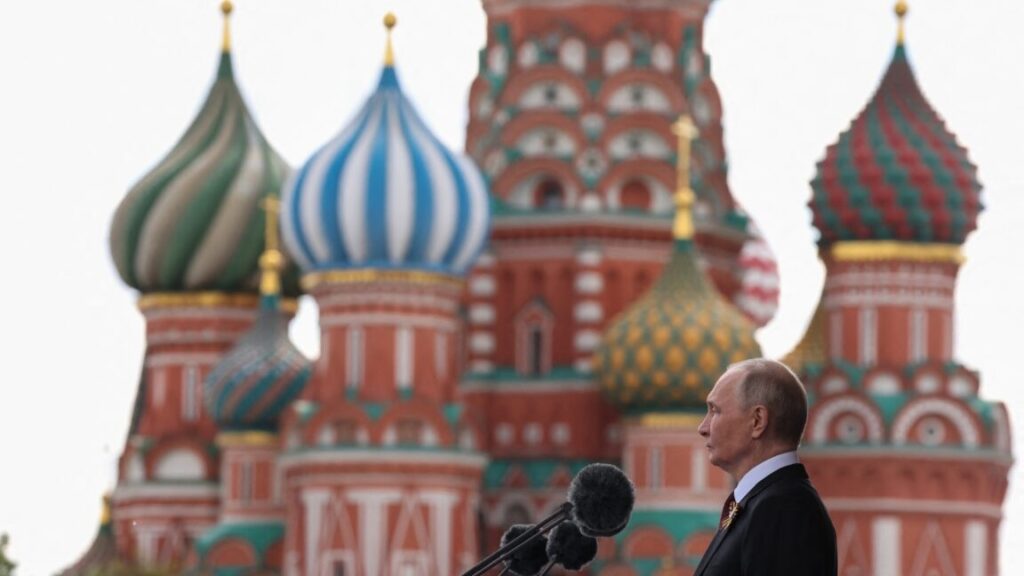

That’s usually not the case when China or Russia (and occasionally Iran or North Korea) launches something into orbit. With rare exceptions, like human spaceflight missions, Chinese and Russian officials don’t publish any specifics about what their rockets are carrying or what altitude they’re going to.

That creates a problem for military operators tasked with monitoring traffic in orbit and breeds anxiety among US forces responsible for making sure potential adversaries don’t gain an edge in space. Will this launch deploy something that can destroy or disable a US satellite? Will this new satellite have a new capability to surveil allied forces on the ground or at sea?

Of course, this is precisely the point of keeping launch details under wraps. The US government doesn’t publish orbital data on its most sensitive satellites, such as spy craft collecting intelligence on foreign governments.

But you can’t hide in low-Earth orbit, a region extending hundreds of miles into space. Col. Raj Agrawal, who commanded Mission Delta 2 until earlier this month, knows this all too well. Agrawal handed over command to Col. Barry Croker as planned after a two-year tour of duty at Mission Delta 2.

Col. Raj Agrawal, then-Mission Delta 2 commander, delivers remarks to audience members during the Mission Delta 2 redesignation ceremony in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on October 31, 2024. Credit: US Space Force

Some space enthusiasts have made a hobby of tracking US and foreign military satellites as they fly overhead, stringing together a series of observations over time to create fairly precise estimates of an object’s altitude and inclination.

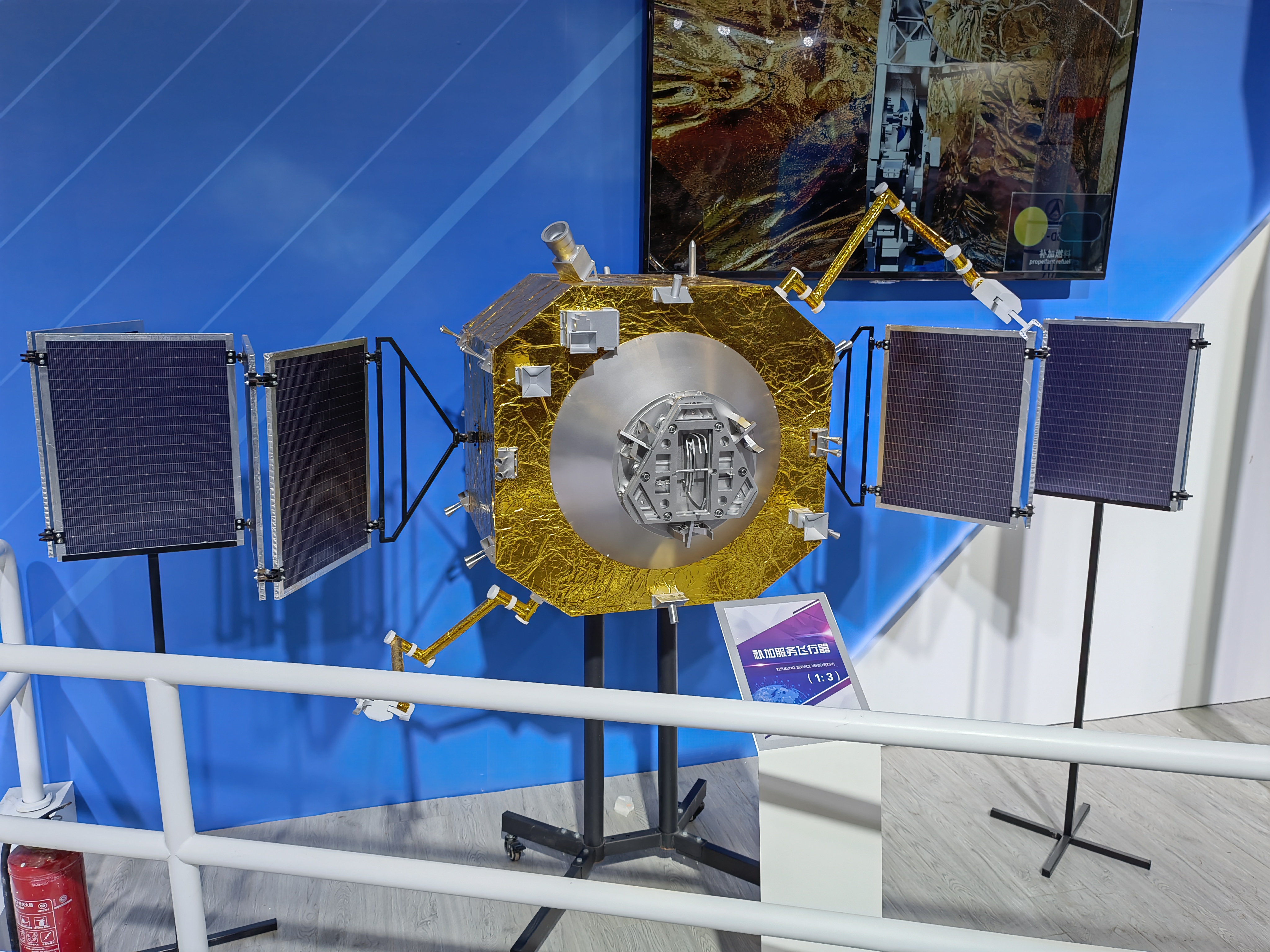

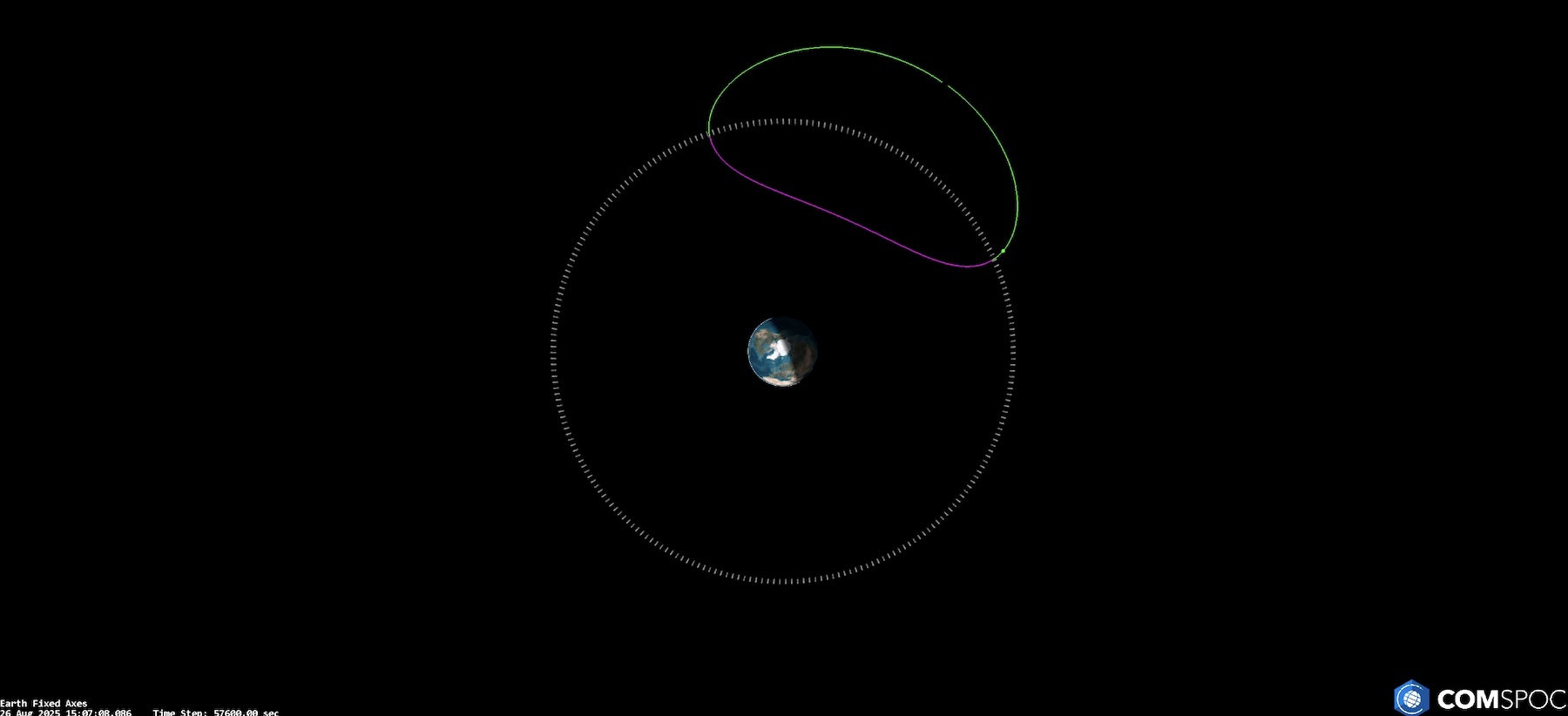

Commercial companies are also getting in on the game of space domain awareness. But most are based in the United States or allied nations and have close partnerships with the US government. Therefore, they only release information on satellites owned by China and Russia. This is how Ars learned of interesting maneuvers underway with a Chinese refueling satellite and suspected Russian satellite killers.

Theoretically, there’s nothing to stop a Chinese company, for example, from taking a similar tack on revealing classified maneuvers conducted by US military satellites.

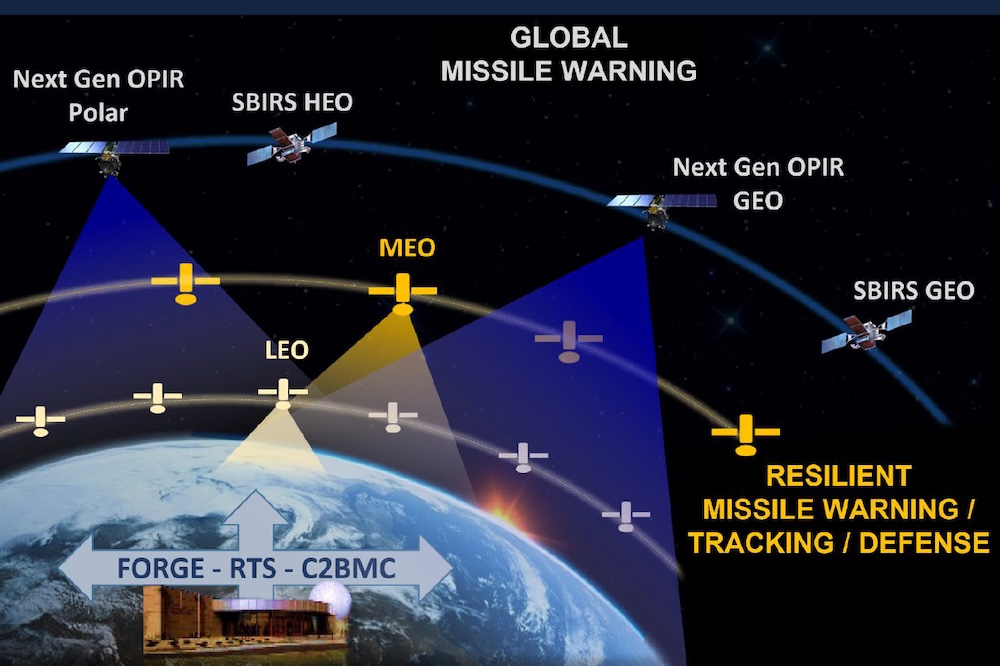

The Space Force has an array of sensors scattered around the world to detect and track satellites and space debris. The 18th and 19th Space Defense Squadrons, which were both under Agrawal’s command at Mission Delta 2, are the units responsible for this work.

Preparing for the worst

One of the most dynamic times in the life of a Space Force satellite tracker is when China or Russia launches something new, according to Agrawal. His command pulls together open source information, such as airspace and maritime warning notices, to know when a launch might be scheduled.

This is not unlike how outside observers, like hobbyist trackers and space reporters, get a heads-up that something is about to happen. These notices tell you when a launch might occur, where it will take off from, and which direction it will go. What’s different for the Space Force is access to top-secret intelligence that might clue military officials in on what the rocket is actually carrying. China, in particular, often declares that its satellites are experimental, when Western analysts believe they are designed to support military activities.

That’s when US forces swing into action. Sometimes, military forces go on alert. Commanders develop plans to detect, track, and target the objects associated with a new launch, just in case they are “hostile,” Agrawal said.

We asked Agrawal to take us through the process his team uses to prepare for and respond to one of these unannounced, or “non-cooperative,” launches. This portion of our interview is published below, lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Ars: Let’s say there’s a Russian or Chinese launch. How do you find out there’s a launch coming? Do you watch for NOTAMs (Notices to Airmen), like I do, and try to go from there?

Agrawal: I think the conversation starts the same way that it probably starts with you and any other technology-interested American. We begin with what’s available. We certainly have insight through intelligence means to be able to get ahead of some of that, but we’re using a lot of the same sources to refine our understanding of what may happen, and then we have access to other intel.

The good thing is that the Space Force is a part of the Intelligence Community. We’re plugged into an entire Intelligence Community focused on anything that might be of national security interest. So we’re able to get ahead. Maybe we can narrow down NOTAMs; maybe we can anticipate behavior. Maybe we have other activities going on in other domains or on the Internet, the cyber domain, and so on, that begin to tip off activity.

Certainly, we’ve begun to understand patterns of behavior. But no matter what, it’s not the same level of understanding as those who just cooperate and work together as allies and friends. And if there’s a launch that does occur, we’re not communicating with that launch control center. We’re certainly not communicating with the folks that are determining whether or not the launch will be safe, if it’ll be nominal, how many payloads are going to deploy, where they’re going to deploy to.

I certainly understand why a nation might feel that they want to protect that. But when you’re fielding into LEO [low-Earth orbit] in particular, you’re not really going to hide there. You’re really just creating uncertainty, and now we’re having to deal with that uncertainty. We eventually know where everything is, but in that meantime, you’re creating a lot of risk for all the other nations and organizations that have fielded capability in LEO as well.

Find, fix, track, target

Ars: Can you take me through what it’s like for you and your team during one of these launches? When one comes to your attention, through a NOTAM or something else, how do you prepare for it? What are you looking for as you get ready for it? How often are you surprised by something with one of these launches?

Agrawal: Those are good questions. Some of it, I’ll be more philosophical on, and others I can be specific on. But on a routine basis, our formation is briefed on all of the launches we’re aware of, to varying degrees, with the varying levels of confidence, and at what classifications have we derived that information.

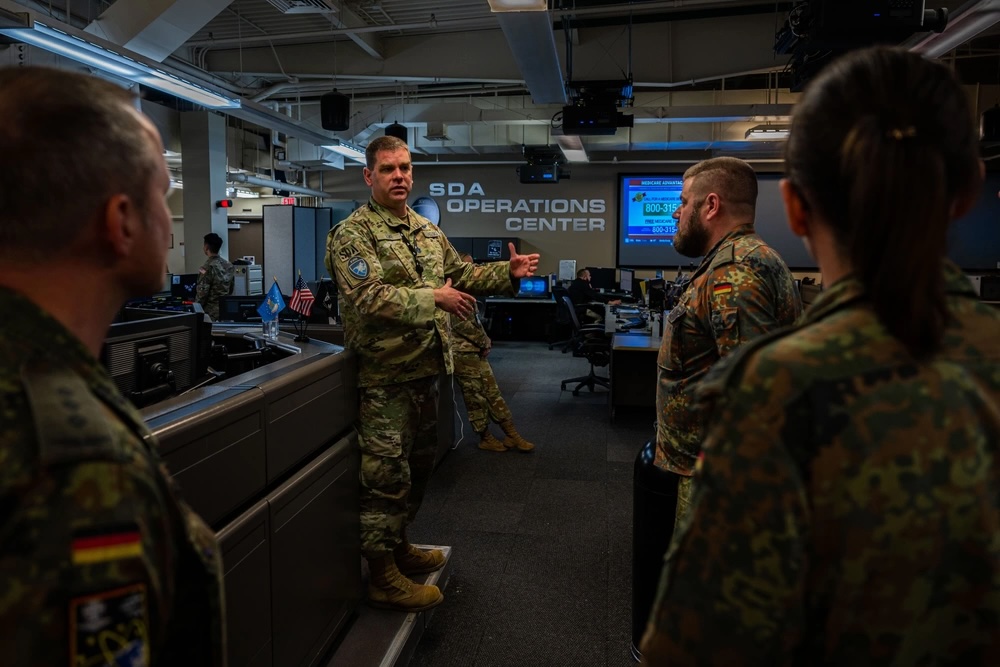

In fact, we also have a weekly briefing where we go into depth on how we have planned against some of what we believe to be potentially higher threats. How many organizations are involved in that mission plan? Those mission plans are done at a very tactical level by captains and NCOs [non-commissioned officers] that are part of the combat squadrons that are most often presented to US Space Command…

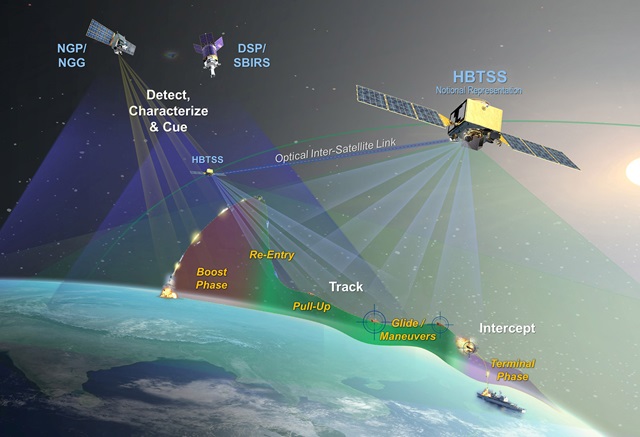

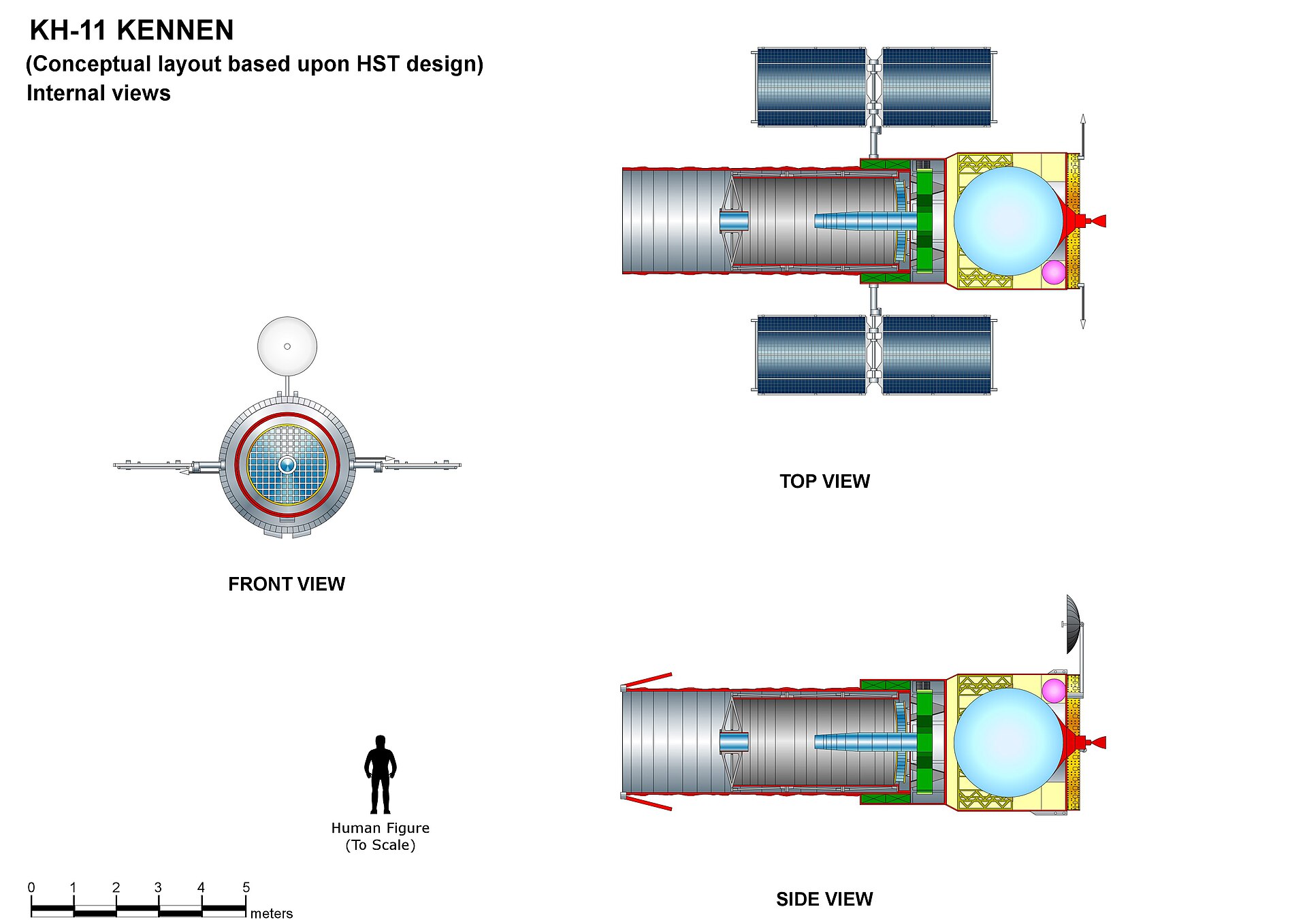

That integrated mission planning involves not just Mission Delta 2 forces but also presented forces by our intelligence delta [Space Force units are called deltas], by our missile warning and missile tracking delta, by our SATCOM [satellite communications] delta, and so on—from what we think is on the launch pad, what we think might be deployed, what those capabilities are. But also what might be held at risk as a result of those deployments, not just in terms of maneuver but also what might these even experimental—advertised “experimental”—capabilities be capable of, and what harm might be caused, and how do we mission-plan against those potential unprofessional or hostile behaviors?

As you can imagine, that’s a very sophisticated mission plan for some of these launches based on what we know about them. Certainly, I can’t, in this environment, confirm or deny any of the specific launches… because I get access to more fidelity and more confidence on those launches, the timing and what’s on them, but the precursor for the vast majority of all these launches is that mission plan.

That happens at a very tactical level. That is now posturing the force. And it’s a joint force. It’s not just us, Space Force forces, but it’s other services’ capabilities as well that are posturing to respond to that. And the truth is that we even have partners, other nations, other agencies, intel agencies, that have capability that have now postured against some of these launches to now be committed to understanding, did we anticipate this properly? Did we not?

And then, what are our branch plans in case it behaves in a way that we didn’t anticipate? How do we react to it? What do we need to task, posture, notify, and so on to then get observations, find, fix, track, target? So we’re fulfilling the preponderance of what we call the kill chain, for what we consider to be a non-cooperative launch, with a hope that it behaves peacefully but anticipating that it’ll behave in a way that’s unprofessional or hostile… We have multiple chat rooms at multiple classifications that are communicating in terms of “All right, is it launching the way we expected it to, or did it deviate? If it deviated, whose forces are now at risk as a result of that?”

A spectator takes photos before the launch of the Long March 7A rocket carrying the ChinaSat 3B satellite from the Wenchang Space Launch Site in China on May 20, 2025. Credit: Meng Zhongde/VCG via Getty Images

Now, we even have down to the fidelity of what forces on the ground or on the ocean may not have capability… because of maneuvers or protective measures that the US Space Force has to take in order to deviate from its mission because of that behavior. The conversation, the way it was five years ago and the way it is today, is very, very different in terms of just a launch because now that launch, in many cases, is presenting a risk to the joint force.

We’re acting like a joint force. So that Marine, that sailor, that special operator on the ground who was expecting that capability now is notified in advance of losing that capability, and we have measures in place to mitigate those outages. And if not, then we let them know that “Hey, you’re not going to have the space capability for some period of time. We’ll let you know when we’re back. You have to go back to legacy operations for some period of time until we’re back into nominal configuration.”

I hope this blows your mind because it blows my mind in the way that we now do even just launch processing. It’s very different than what we used to do.

Ars: So you’re communicating as a team in advance of a launch and communicating down to the tactical level, saying that this launch is happening, this is what it may be doing, so watch out?

Agrawal: Yeah. It’s not as simple as a ballistic missile warning attack, where it’s duck and cover. Now, it’s “Hey, we’ve anticipated the things that could occur that could affect your ability to do your mission as a result of this particular launch with its expected payload, and what we believe it may do.” So it’s not just a general warning. It’s a very scoped warning.

As that launch continues, we’re able to then communicate more specifically on which forces may lose what, at what time, and for how long. And it’s getting better and better as the rest of the US Space Force, as they present capability trained to that level of understanding as well… We train this together. We operate together and we communicate together so that the tactical user—sometimes it’s us at US Space Force, but many times it’s somebody on the surface of the Earth that has to understand how their environment, their capability, has changed as a result of what’s happening in, to, and from space.

Ars: The types of launches where you don’t know exactly what’s coming are getting more common now. Is it normal for you to be on this alert posture for all of the launches out of China or Russia?

Agrawal: Yeah. You see it now. The launch manifest is just ridiculous, never mind the ones we know about. The ones that we have to reach out into the intelligence world and learn about, that’s getting ridiculous, too. We don’t have to have this whole machine postured this way for cooperative launches. So the amount of energy we’re expending for a non-cooperative launch is immense. We can do it. We can keep doing it, but you’re just putting us on alert… and you’re putting us in a position where we’re getting ready for bad behavior with the entire general force, as opposed to a cooperative launch, where we can anticipate. If there’s an anomaly, we can anticipate those and work through them. But we’re working through it with friends, and we’re communicating.

We’re not having to put tactical warfighters on alert every time … but for those payloads that we have more concern about. But still, it’s a very different approach, and that’s why we are actively working with as many nations as possible in Mission Delta 2 to get folks to sign on with Space Command’s space situational awareness sharing agreements, to go at space operations as friends, as allies, as partners, working together. So that way, we’re not posturing for something higher-end as a result of the launch, but we’re doing this together. So, with every nation we can, we’re getting out there—South America, Africa, every nation that will meet with us, we want to meet with them and help them get on the path with US Space Command to share data, to work as friends, and use space responsibly.”

A Long March 3B carrier rocket carrying the Shijian 21 satellite lifts off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center on October 24, 2021. Credit: Li Jieyi/VCG via Getty Images

Ars: How long does it take you to sort out and get a track on all of the objects for an uncooperative launch?

Agrawal: That question is a tough one to answer. We can move very, very quickly, but there are times when we have made a determination of what we think something is, what it is and where it’s going, and intent; there might be some lag to get it into a public catalog due to a number of factors, to include decisions being made by combatant commanders, because, again, our primary objective is not the public-facing catalog. The primary objective is, do we have a risk or not?

If we have a risk, let’s understand, let’s figure out to what degree do we think we have to manage this within the Department of Defense. And to what degree do we believe, “Oh, no, this can go in the public catalog. This is a predictable elset (element set)”? What we focus on with (the public catalog) are things that help with predictability, with spaceflight safety, with security, spaceflight security. So you sometimes might see a lag there, but that’s because we’re wrestling with the security aspect of the degree to which we need to manage this internally before we believe it’s predictable. But once we believe it’s predictable, we put it in the catalog, and we put it on space-track.org. There’s some nuance in there that isn’t relative to technology or process but more on national security.

On the flip side, what used to take hours and days is now getting down to seconds and minutes. We’ve overhauled—not 100 percent, but to a large degree—and got high-speed satellite communications from sensors to the centers of SDA (Space Domain Awareness) processing. We’re getting higher-end processing. We’re now duplicating the ability to process, duplicating that capability across multiple units. So what used to just be human labor intensive, and also kind of dial-up speed of transmission, we’ve now gone to high-speed transport. You’re seeing a lot of innovation occur, and a lot of data fusion occur, that’s getting us to seconds and minutes.

The military’s squad of satellite trackers is now routinely going on alert Read More »