Office problems on Windows 10? Microsoft’s response will soon be “upgrade to 11.”

Microsoft’s advertised end-of-support date for Windows 10 is October 14, 2025. But in reality, the company will gradually wind down support for the enduring popular operating system over the next three years. Microsoft would really like you to upgrade to Windows 11, especially if it also means upgrading to a new PC, but it also doesn’t want to leave hundreds of millions of home and business PCs totally unprotected.

Those competing goals have led to lots of announcements and re-announcements and clarifications about updates for both Windows 10 itself and the Office/Microsoft 365 productivity apps that many Windows users run on their PCs.

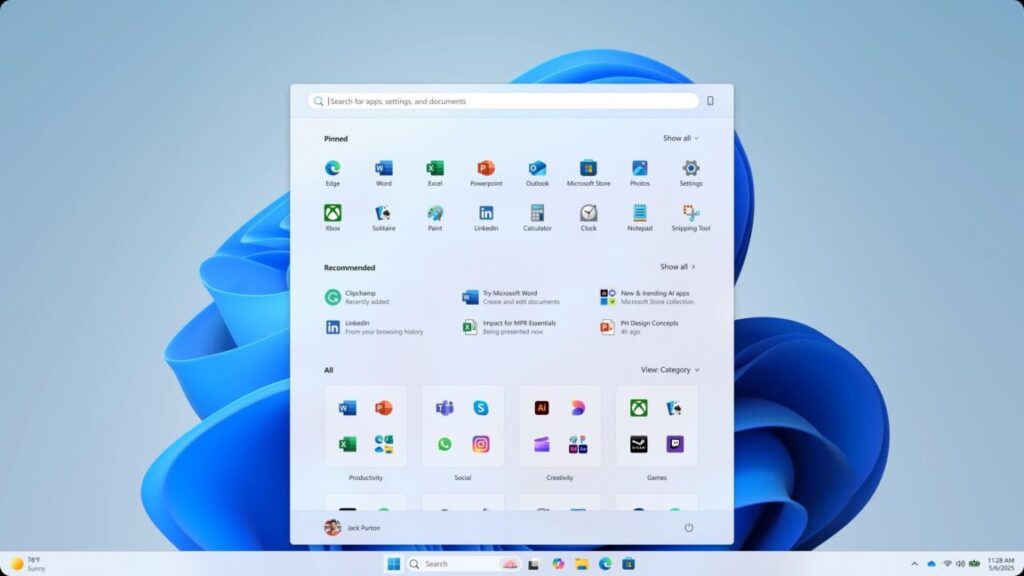

Today’s addition to the pile comes via The Verge, which noticed an update to a support document that outlined when Windows 10 PCs would stop receiving new features for the continuously updated Microsoft 365 apps. Most home users will stop getting new features in August 2026, while business users running the Enterprise versions can expect to stop seeing new features in either October 2026 or January 2027, depending on the product they’re using.

Microsoft had previously committed to supporting its Office apps through October 2028—both the Microsoft 365 versions and perpetually licensed versions like Office 2021 and Office 2024 that don’t get continuous feature updates. That timeline isn’t changing, but it will apparently only cover security and bug-fixing updates rather than updates that add new features.

And while the apps will still be getting updates, Microsoft’s support document makes it clear that users won’t always be able to get fixes for bugs that are unique to Windows 10. If an Office issue exists solely on Windows 10 but not on Windows 11, the official guidance from Microsoft support is that users should upgrade to Windows 11; any support for Windows 10 will be limited to “troubleshooting assistance only,” and “technical workarounds might be limited or unavailable.”

Office problems on Windows 10? Microsoft’s response will soon be “upgrade to 11.” Read More »