Yet another co-founder departs Elon Musk’s xAI

Other recent high-profile xAI departures include general counsel Robert Keele, communications executives Dave Heinzinger and John Stoll, head of product engineering Haofei Wang, and CFO Mike Liberatore, who left for a role at OpenAI after just 102 days of what he called “120+ hour weeks.”

A different company

Wu leaves a company that is in a very different place than it was when he helped create it in 2023. His departure comes just days after CEO Elon Musk merged xAI with SpaceX, a move Musk says will allow for orbiting data centers and, eventually, “scaling to make a sentient sun to understand the Universe and extend the light of consciousness to the stars!” But some see the move as more of a financial engineering play, combining xAI’s nearly $1 billion a year in losses and SpaceX’s roughly $8 billion in annual profits into a single, more IPO-ready entity.

Musk previously rolled social media network X (formerly Twitter) into a unified entity with xAI back in March. At the time of the deal, X was valued at $33 billion, 25 percent less than Musk paid for the social network in 2022.

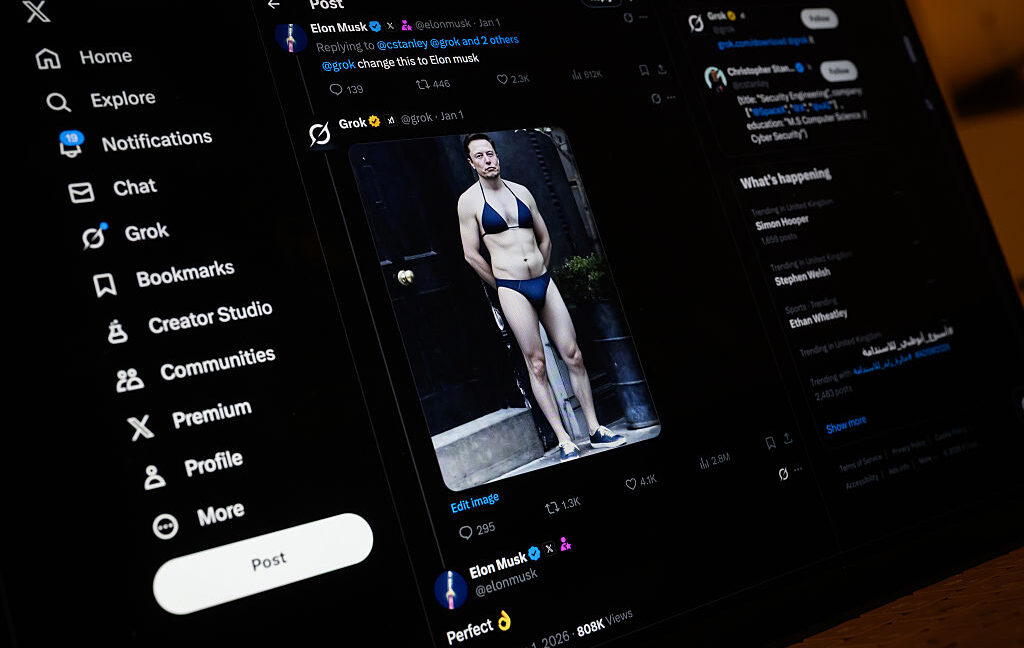

xAI has faced a fresh wave of criticism in recent months over Grok’s willingness to generate sexualized images of minors. That has led to an investigation by California’s attorney general and a police raid of the company’s Paris offices.

Yet another co-founder departs Elon Musk’s xAI Read More »